Nebo or Nabu

By M. K. Van Rensselaer

By M. K. Van Rensselaer

A great Chaldean god was Nebo, mentioned in Isaiah xlvi:1, “Bel boweth down, Nebo stoopeth,” and he had an immense influence over the lives of the Assyrians and Babylonians, extending over centuries. In primitive times nothing was undertaken without an attempt to consult the wishes of the superior gods, and it is interesting to trace through the tablets on which are inscribed the wonderful cuneiform inscriptions, discovered and deciphered during the past fifty years, how the people were taught by their prophets or priests to consult the predestinations of Nebo, who inscribed at birth what would befall each person during life. Nebo had many names or designations. He was called Laghlaghghi-Gar, or illuminator; Gishdar, or god of the sceptre; Ilu-tashmit, or god of revelations; and the spouse of Tashmit; his name signifies Proclaimer Herald in Assyrian, and Height in Hebrew.

Nebo, called Nabu by the Babylonians, was the son of Enlil, or Marduk, the Merodach of the Bible (Jeremiah l:2), who became merged in the Jupiter of the Romans. Nebo was the husband of Tashmitum, or Tashmit, or Tashmetu, sometimes called Erna. Her name is translated as signifying “revelation,” “she who listens,” or “she who intercedes.” She is frequently invoked and besought to placate her more important spouse, or she is appealed to by worshippers to intercede with her consort to reveal what he had prophesied on the “tablets of fate.”

As the grandson of Ea, who was the god of doctors, Nebo inherited the privileges of healing. He also presided at birth and death, and could cure diseases. One of his symbols seems peculiar and is still retained on the Tarots. It is a sword, for in the minds of the men of his day a pestilence was a certain follower of war. Although Nebo was not the god of war, he was first its herald and then the healer of the sick or wounded, so it was under these conditions that a sword became his attribute.

Nebo shared with Shamash, Gula, and Nergal of Assyrian mythology, the power of restoring the dead to life, which, being interpreted, means curing the ill, whether from disease or sin.

It was to Nebo that the Assyrian kings ascribed their wisdom, for he was deemed to be the source of all knowledge, and the wonderful inventor of the art of writing that enabled the wise men who were his priests to preserve the records of the different reigns and the history of wars, the description of buildings and their donors, of deeds of valour and of charity, for the enlightenment of posterity.

The great temple built at Calah in the time of Ram-man-nerari III (812-783 B. C.) is inscribed with a dedicatory inscription placed by the king on the statue of Nebo. It closes with the sentence:

“Oh! posterity, trust in Nabu,

Trust in no other god.”

Nebo was also the patron of agriculture, who taught the husbandmen when to plant, the best time for irrigating, and a favourable time for the harvest. Being the messenger from heaven to earth, one of his symbols was the lightning. This emblem is preserved on the Japanese cards, although it is probably accidental. A hymn to Nebo attests his having lightning as an attribute, and the tablet upon which it was transcribed in cuneiform characters has been translated as follows:

“Lord of Borsippa, Son of E-Sagila! Oh, Lord, to thy power

There is no rival. Oh, Nebo, to thy Temple E-Zida there is no rival,

Or to thy home, Babylon. Thy weapon is the lightning,

From the mouth of which no breath does issue or blood flow.

Thy commands are as unchangeable as the Heavens,

Where thou art Supreme.”

The chief temple of Nebo was at Borsippa, on the opposite side of the Euphrates to Babylon; the town was sometimes called Babylon II. Nebo’s temple was styled E-Zida, the true house, and E-Sagila signified the lofty house, which was the temple of his father, Marduk. The connection with lightning is too marked to be overlooked when studying the derivation of Mercury’s attributes from those of Nebo.

The mighty king Ashur-banapal invokes Nebo on thousands of tablets that have been found in his great library. Nebo is called “the opener of the ears to understanding,” “he who gives the sceptre of sovereignty to kings, that they may rule over all lands,” “the upholder of the world,” “the general overlord and the seer.” All these attributes were combined with the scientific attainments of Nebo, and he was proclaimed as the inventor of language and the art of writing, together with being the great teacher and encourager of learning and scientific investigations. This is all emphasised by his numerous titles, such as “Speaker,” which is said to be derived from his name, signifying “to speak,” or “one who announces the fate of mankind,” which was another inheritance of Mercury’s when he was called the “Messenger of the Gods.” The attribute, then, in both cases, was the emblematic Sceptre of the ruler, the caduceus. The Sceptre was also named by the Assyrians “the Proclaimer,” and was variously represented, sometimes by the Staff with twisted serpents, although in earlier times it was generally pictured as stylus, which was closely copied in the representations of Thoth. The entwining serpents of the caduceus sacred to Mercury were directly inherited from votive emblems peculiar to the Babylonians, and they received force and significance after the rods of the Egyptian magi were turned into serpents and swallowed by the rod of Aaron.

When Nebo is called “Ilu-tashmit,” or god of Revelations, who teaches through his invention of writing and of speech, he is then regarded as a soothsayer or prophet. The Hebrew word for prophet is Nabi, and this leads to the interesting discussion that was started by Mr. Chatto in his “History of Playing Cards” (page 22), when he speculates on the name of Naibi, given to cards by the earliest Italian writers who mention them. As Naypes or Naipes is still the name printed on the wrappers and on the Four of Cups of Spanish cards, it evidently was connected with prophesy, and this card has peculiar values and significances among the gypsy fortune-tellers. Mr. Chatto states that in Hindustani the word Na-eeb or Naib signifies a viceroy or overlord, and quotes from “several Spanish writers” who have “decidedly asserted that the word Naipes, signifying cards, whatever it might originally have meant, was derived from the Arabic.” All the writers on playing cards quote from Corvelluzzo, who states: “In the year 1379 was brought into Viterbo the game of cards, which comes from the country of the Saracens and is with them called Naib.” The Arabian “divining arrows” are always made from a tree called Nabaa.

This little history, which is one of the earliest records of cards that were then no longer considered prophetic, has seemed to close all inquiry into the birth of games or their vehicle. No inquiry was therefore made into anything preceding this period. However, had cards been regarded as the survival of one of the most ancient of cults, connected with it by its traditions of prophesy or fortune-telling, the true story might have been unravelled centuries ago, for a study of the traditions, religions or superstitions of Africa and Asia would have revealed that Naibi (the name given at that time to cards) meant prophesy or revelation, and was inherited from the great “Writer on the Tablets of Fate,” Nebo the prophet, the Assyrian god. The prophets of the Bible were called Nabi, and it seems to be no accident that the mountain dedicated to Nebo and bearing his name should have been selected for the death place of the great prophet, Moses.

In the earliest histories of Assyrian mythology Nebo was not the influential personage that he became afterwards. But it was still early days when he was accorded the honour of having one of the planets named for him, which afterwards became identified with Mercury. When Nebo took his place among the mystic seven great gods, he found associated with him Marduk (or Jupiter), Nergal (or Mars), Ishtar (or Venus), Nineb (or Saturn), the Sun, represented in a chariot drawn by horses, as copied in the seventh card of the Atouts, and the Moon (Nan-nar), who was called the “Heifer of Anu,” and was the presiding genius. She received the name because the horns of the new moon resembled those of a cow. Her Assyrian temple was at Ur of the Chaldeans, and she was also worshipped in Egypt and is represented by the eighteenth Atout. Her horns are always typical of wisdom and prophesy, and, as such, are used on Michael Angelo’s famous statue of Moses.

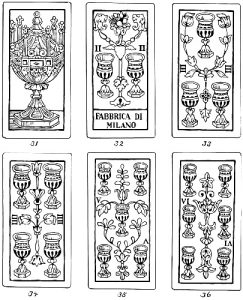

Early Italian Tarots

Pip Cards of the Cup Suit

The first month of the Babylonian year was sacred to Nebo and his father, Marduk, and was called Nesan. The Egyptians made Thoth, or September, the first month; that began August 29th, as we figure it, with the rising of the Dog Star, which also was sacred to that god. This is symbolised in the seventeenth Atout, called The Stars, represented by an oblation to Osiris.

Daily sacrifices were made to Nebo, the offerings being bulls, and other animals, fish, birds, vegetables, honey, wine, oil and cream. Their technical term was Sattuku and Gina. It is probable that the wild boar was sacred to Nebo, as it was to Mercury, being one of the animals sacrificed to the latter, and the emblem is still found on the Two of Bells of the German cards. The boar was sacred among the Assyrians, and its flesh was forbidden on certain days in the Babylonian calendar. Its name was Nin-shakh, or Pap-sukal, meaning “Divine Messenger,” the name that was synonymous with that of Nebo.

There were many great ceremonies connected with the rites of Nebo, for the scientists, doctors, warriors and kings were all anxious to conciliate the arbiter of their fate, and there were many statues erected in his honour all over the land. The one representing him that was kept in E-Sagila, at Borsippa, called by Nebuchadnezzar “the house of the temple of the world,” meaning the lofty home, was yearly conducted with great ceremonies across the Euphrates in a car, or ark, shaped like a ship, in order that Nebo might pay homage at the temple of his father, Marduk.

The cult of Nebo reached its height when Nabu-polassar (626 B. C.), Nebu-chadnezzar (605 B. C.), and Nabonnedos (556 B. C.), adopted his name, thereby throwing themselves on his mercy, or invoking his protection. Nebuchadnezzar adopted it as signifying “Oh, god Nebu, protect my boundaries.”

About the ninth century before Christ there were innumerable temples devoted to the cult of Nebo dotted over the land, for those were troublous times, and, doubtless, the rulers and their people were anxious to have all the advice that they could obtain from the “Arbiter of Fate.” He was styled “the all-wise who guides the stylus of the scribes,” as well as “the possessor of wisdom,” and “the seer who guides all gods.” These inscriptions are found in many places, not only on the temples but on clay tablets.

Ashur-banipal extols Nebo on many of the tablets found in his great library at Nineveh, thanking him for his instructions and the inspiration that enabled the king to record in writing his valiant deeds, that were thus preserved for the benefit of his subjects. One of them reads, “write for posterity.”

The Assyrians invaded Egypt many times, and the Egyptians in return overran Palestine, Persia, Babylonia and Assyria, so that by intermarriage and constant intercourse the scientific attainments and the mythologies of both became influenced or mingled.

Although the capital of Menephtah, the Pharaoh of the Exodus, was at Thebes, the site of the great temple of Thoth and the favourite residence of “the Ruler” was Zoan, or Sau, as it is now called, which is three miles from Goshen. It was there that Moses and Aaron had their interviews. From that time on Thoth and Nebo became almost one god, and it is by no means stretching a point to connect the cults of Assyria and Babylonia with those of Egypt. Isaiah xix:23 says: “There shall be a highway out of Egypt to Assyria, and the Assyrian shall come into Egypt and the Egyptian into Assyria, and the Egyptians shall serve with the Assyrians.” In the same chapter (third verse) we find: “And they shall seek to the idols, and to the charmers, and to them that have familiar spirits, and to the wizards.” It is, therefore, but a simple conclusion to suppose that the magi of Egypt adopted the great tablet writer of the Assyrians as one of their inspiring gods, and, that afterwards, when the pair were introduced to Europeans, they were merged into Mercury, while “The Book of the Writer” became known as “The Book of Thoth Hermes Trismegistus” (three times great), now called the Tarot pack of cards.

“The Bearer of the Fate Tablets,” dedicated to Nebuchadnezzar at Borsippa, has been translated, “Oh! Nabu! On thy unchangeable Tablets which determine the boundaries of Heaven and Earth, decree the length of my days. Write down posterity.” Which we would read, “Tell me how long I am to live and bestow children upon me.”

There is a colophon in Semitic Babylonian, written by Nabu-baladhsuigbi, son of Mitsircea (the Egyptian), probably during the reign of Nabonidus, the father of Belshazzar, that is also an invocation in the same style. The inscription of Tiglath-Pileser I, king of Assyria, which “is the longest and most important of early Assyrian records,” says Professor Sayce, dates from about 1106 B. C. This inscription was found under the foundations of the four corners of the temple of Kileh Shergha, the ancient city of Asshur, and is now in the British Museum. The one hundred and fifth sentence mentions divining rods as the “Oracle of the Great Divinities,” being placed within the temple. “This Elalla,” says Professor Sayce, “was a stem of papyrus covered with writing.”

Many tablets of Assyrian times have been deciphered from the cuneiform text and are designated as “Tablets of Grace,” or “Tablets of Good Works.” These are supposed to be those that Nebo wrote describing the virtues of men. Besides these, the Babylonians mentioned tablets on which the sins of the evil were recorded. The pious worshipper, therefore, prays that the Tablet of his sins and iniquities may be destroyed, saying: “May the Tablet of my sins be broken,” showing how prevalent was the belief that Nebo controlled fate entirely, both when predicting the future and also after death, and in this Thoth resembles him closely.

Similar connections are met with in the Old Testament, when Moses cries, “Forgive their sins—; and if not, blot me, I pray thee, out of thy book which thou hast written.” (Exodus xxxii:32.) The belief that such records are kept by the Almighty is referred to also in the New Testament. “Your names are written in Heaven.” (St. Luke x:20.) The verse in Ezekiel ix:2, “One man among them was clothed in linen, with a writer’s inkhorn by his side,” is supposed to refer to Nebo, “the Heavenly Scribe.”

In a long cuneiform text inscribed on a terra cotta prism found at Nineveh, King Asshur-banapal glories in having received from Nebo and Tashmitu (his consort) the power to understand “the art of tablet-writing.” In “Babylonian Magic and Sorcery from the British Museum,” by Leonard W. King, M. A., Assistant in the Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, British Museum, there are tablets invoking the protection of Nebo as well as of other gods. One of them has been translated as follows:

“Oh! Hero Prince, First born of Marduk;

Oh! prudent ruler of Spring of Zarpanitu;

Oh! Nabu, Bearer of the Tablet of the destiny of the Gods, Director of Isagila,

Lord of Izida, Shadow of Borsippa,

Darling of Ia, Giver of Life,

Prince of Babylon, Protector of the Living.”

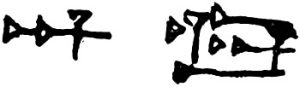

It may be stretching a point to observe that the “arrow-headed” letters on the tablets of Babylonia closely resemble a sheaf of arrows that have fallen haphazard. But this may be seen in the name of the god Nebo.

*******

This is taken from Prophetical, Educational and Playing Cards.