Mr. Morris’s Poems

[Note: This is taken From Andrew Lang’s Adventures Among Books.]

[Note: This is taken From Andrew Lang’s Adventures Among Books.]

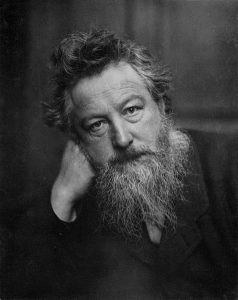

“Enough,” said the pupil of the wise Imlac, “you have convinced me that no man can be a poet.” The study of Mr. William Morris’s poems, in the new collected edition, has convinced me that no man, or, at least, no middle-aged man, can be a critic. I read Mr. Morris’s poems (thanks to the knightly honours conferred on the Bard of Penrhyn, there is now no ambiguity as to ‘Mr. Morris’), but it is not the book only that I read. The scroll of my youth is unfolded. I see the dear place where first I perused “The Blue Closet”; the old faces of old friends flock around me; old chaff, old laughter, old happiness re-echo and revive. St. Andrews, Oxford, come before the mind’s eye, with

“Many a place

That’s in sad case

Where joy was wont afore, oh!”

as Minstrel Burne sings. These voices, faces, landscapes mingle with the music and blur the pictures of the poet who enchanted for us certain hours passed in the paradise of youth. A reviewer who finds himself in this case may as well frankly confess that he can no more criticise Mr. Morris dispassionately than he could criticise his old self and the friends whom he shall never see again, till he meets them

“Beyond the sphere of time,

And sin, and grief’s control,

Serene in changeless prime

Of body and of soul.”

To write of one’s own “adventures among books” may be to provide anecdotage more or less trivial, more or less futile, but, at least, it is to write historically. We know how books have affected, and do affect ourselves, our bundle of prejudices and tastes, of old impressions and revived sensations. To judge books dispassionately and impersonally, is much more difficult—indeed, it is practically impossible, for our own tastes and experiences must, more or less, modify our verdicts, do what we will. However, the effort must be made, for to say that, at a certain age, in certain circumstances, an individual took much pleasure in “The Life and Death of Jason,” the present of a college friend, is certainly not to criticise “The Life and Death of Jason.”

There have been three blossoming times in the English poetry of the nineteenth century. The first dates from Wordsworth, Coleridge, Scott, and, later, from Shelley, Byron, Keats. By 1822 the blossoming time was over, and the second blossoming time began in 1830-1833, with young Mr. Tennyson and Mr. Browning. It broke forth again, in 1842 and did not practically cease till England’s greatest laureate sang of the “Crossing of the Bar.” But while Tennyson put out his full strength in 1842, and Mr. Browning rather later, in “Bells and Pomegranates” (“Men and Women”), the third spring came in 1858, with Mr. Morris’s “Defence of Guenevere,” and flowered till Mr. Swinburne’s “Atalanta in Calydon” appeared in 1865, followed by his poems of 1866. Mr. Rossetti’s book of 1870 belonged, in date of composition, mainly to this period.

In 1858, when “The Defence of Guenevere” came out, Mr. Morris must have been but a year or two from his undergraduateship. Every one has heard enough about his companions, Mr. Burne Jones, Mr. Rossetti, Canon Dixon, and the others of the old Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, where Mr. Morris’s wonderful prose fantasies are buried. Why should they not be revived, these strangely coloured and magical dreams? As literature, I prefer them vastly above Mr. Morris’s later romances in prose—“The Hollow Land” above “News from Nowhere!” Mr. Morris and his friends were active in the fresh dawn of a new romanticism, a mediæval and Catholic revival, with very little Catholicism in it for the most part. This revival is more “innerly,” as the Scotch say, more intimate, more “earnest” than the larger and more genial, if more superficial, restoration by Scott. The painful doubt, the scepticism of the Ages of Faith, the dark hours of that epoch, its fantasy, cruelty, luxury, no less than its colour and passion, inform Mr. Morris’s first poems. The fourteenth and the early fifteenth century is his “period.” In “The Defence of Guenevere” he is not under the influence of Chaucer, whose narrative manner, without one grain of his humour, inspires “The Life and Death of Jason” and “The Earthly Paradise.” In the early book the rugged style of Mr. Browning has left a mark. There are cockney rhymes, too, such as “short” rhyming to “thought.” But, on the whole, Mr. Morris’s early manner was all his own, nor has he ever returned to it. In the first poem, “The Queen’s Apology,” is this passage:—

“Listen: suppose your time were come to die,

And you were quite alone and very weak;

Yea, laid a-dying, while very mightily“The wind was ruffling up the narrow streak

Of river through your broad lands running well:

Suppose a hush should come, then some one speak:“‘One of these cloths is heaven, and one is hell,

Now choose one cloth for ever, which they be,

I will not tell you, you must somehow tell“‘Of your own strength and mightiness; here, see!’

Yea, yea, my lord, and you to ope your eyes,

At foot of your familiar bed to see“A great God’s angel standing, with such dyes,

Not known on earth, on his great wings, and hands,

Held out two ways, light from the inner skies“Showing him well, and making his commands

Seem to be God’s commands, moreover, too,

Holding within his hands the cloths on wands;“And one of these strange choosing-cloths was blue,

Wavy and long, and one cut short and red;

No man could tell the better of the two.“After a shivering half-hour you said,

‘God help! heaven’s colour, the blue;’ and he said, ‘Hell.’

Perhaps you then would roll upon your bed,“And cry to all good men that loved you well,

‘Ah, Christ! if only I had known, known, known.’”

There was nothing like that before in English poetry; it has the bizarrerie of a new thing in beauty. How far it is really beautiful how can I tell? How can I discount the “personal bias”? Only I know that it is unforgettable. Again (Galahad speaks):—

“I saw

One sitting on the altar as a throne,

Whose face no man could say he did not know,

And, though the bell still rang, he sat alone,

With raiment half blood-red, half white as snow.”

Such things made their own special ineffaceable impact.

Leaving the Arthurian cycle, Mr. Morris entered on his especially sympathetic period—the gloom and sad sunset glory of the late fourteenth century, the age of Froissart and wicked, wasteful wars. To Froissart it all seemed one magnificent pageant of knightly and kingly fortunes; he only murmurs a “great pity” for the death of a knight or the massacre of a town. It is rather the pity of it that Mr. Morris sees: the hearts broken in a corner, as in “Sir Peter Harpedon’s End,” or beside “The Haystack in the Floods.” Here is a picture like life of what befell a hundred times. Lady Alice de la Barde hears of the death of her knight:—

“ALICE

“Can you talk faster, sir?

Get over all this quicker? fix your eyes

On mine, I pray you, and whate’er you see

Still go on talking fast, unless I fall,

Or bid you stop.“SQUIRE

“I pray your pardon then,

And looking in your eyes, fair lady, say

I am unhappy that your knight is dead.

Take heart, and listen! let me tell you all.

We were five thousand goodly men-at-arms,

And scant five hundred had he in that hold;

His rotten sandstone walls were wet with rain,

And fell in lumps wherever a stone hit;

Yet for three days about the barriers there

The deadly glaives were gather’d, laid across,

And push’d and pull’d; the fourth our engines came;

But still amid the crash of falling walls,

And roar of bombards, rattle of hard bolts,

The steady bow-strings flash’d, and still stream’d out

St. George’s banner, and the seven swords,

And still they cried, ‘St. George Guienne,’ until

Their walls were flat as Jericho’s of old,

And our rush came, and cut them from the keep.”

The astonishing vividness, again, of the tragedy told in “Geffray Teste Noire” is like that of a vision in a magic mirror or a crystal ball, rather than like a picture suggested by printed words. “Shameful Death” has the same enchanted kind of presentment. We look through a “magic casement opening on the foam” of the old waves of war. Poems of a pure fantasy, unequalled out of Coleridge and Poe, are “The Wind” and “The Blue Closet.” Each only lives in fantasy. Motives, and facts, and “story” are unimportant and out of view. The pictures arise distinct, unsummoned, spontaneous, like the faces and places which are flashed on our eyes between sleeping and waking. Fantastic, too, but with more of a recognisable human setting, is “Golden Wings,” which to a slight degree reminds one of Théophile Gautier’s Château de Souvenir.

“The apples now grow green and sour

Upon the mouldering castle wall,

Before they ripen there they fall:

There are no banners on the tower,The draggled swans most eagerly eat

The green weeds trailing in the moat;

Inside the rotting leaky boat

You see a slain man’s stiffen’d feet.”

These, with “The Sailing of the Sword,” are my own old favourites. There was nothing like them before, nor will be again, for Mr. Morris, after several years of silence, abandoned his early manner. No doubt it was not a manner to persevere in, but happily, in a mood and a moment never to be re-born or return, Mr. Morris did fill a fresh page in English poetry with these imperishable fantasies. They were absolutely neglected by “the reading public,” but they found a few staunch friends. Indeed, I think of “Guenevere” as FitzGerald did of Tennyson’s poems before 1842. But this, of course, is a purely personal, probably a purely capricious, estimate. Criticism may aver that the influence of Mr. Rossetti was strong on Mr. Morris before 1858. Perhaps so, but we read Mr. Morris first (as the world read the “Lay” before “Christabel”), and my own preference is for Mr. Morris.

It was after eight or nine years of silence that Mr. Morris produced, in 1866 or 1867, “The Life and Death of Jason.” Young men who had read “Guenevere” hastened to purchase it, and, of course, found themselves in contact with something very unlike their old favourite. Mr. Morris had told a classical tale in decasyllabic couplets of the Chaucerian sort, and he regarded the heroic age from a mediæval point of view; at all events, not from an historical and archæological point of view. It was natural in Mr. Morris to “envisage” the Greek heroic age in this way, but it would not be natural in most other writers. The poem is not much shorter than the “Odyssey,” and long narrative poems had been out of fashion since “The Lord of the Isles” (1814).

All this was a little disconcerting. We read “Jason,” and read it with pleasure, but without much of the more essential pleasure which comes from magic and distinction of style. The peculiar qualities of Keats, and Tennyson, and Virgil are not among the gifts of Mr. Morris. As people say of Scott in his long poems, so it may be said of Mr. Morris—that he does not furnish many quotations, does not glitter in “jewels five words long.”

In “Jason” he entered on his long career as a narrator; a poet retelling the immortal primeval stories of the human race. In one guise or another the legend of Jason is the most widely distributed of romances; the North American Indians have it, and the Samoans and the Samoyeds, as well as all Indo-European peoples. This tale, told briefly by Pindar, and at greater length by Apollonius Rhodius, and in the “Orphica,” Mr. Morris took up and handled in a single and objective way. His art was always pictorial, but, in “Jason” and later, he described more, and was less apt, as it were, to flash a picture on the reader, in some incommunicable way.

In the covers of the first edition were announcements of the “Earthly Paradise”: that vast collection of the world’s old tales retold. One might almost conjecture that “Jason” had originally been intended for a part of the “Earthly Paradise,” and had outgrown its limits. The tone is much the same, though the “criticism of life” is less formally and explicitly stated.

For Mr. Morris came at last to a “criticism of life.” It would not have satisfied Mr. Matthew Arnold, and it did not satisfy Mr. Morris! The burden of these long narrative poems is vanitas vanitatum: the fleeting, perishable, unsatisfying nature of human existence, the dream “rounded by a sleep.” The lesson drawn is to make life as full and as beautiful as may be, by love, and adventure, and art. The hideousness of modern industrialism was oppressing to Mr. Morris; that hideousness he was doing his best to relieve and redeem, by poetry, and by all the many arts and crafts in which he was a master. His narrative poems are, indeed, part of his industry in this field. He was not born to slay monsters, he says, “the idle singer of an empty day.” Later, he set about slaying monsters, like Jason, or unlike Jason, scattering dragon’s teeth to raise forces which he could not lay, and could not direct.

I shall go no further into politics or agitation, and I say this much only to prove that Mr. Morris’s “criticism of life,” and prolonged, wistful dwelling on the thought of death, ceased to satisfy himself. His own later part, as a poet and an ally of Socialism, proved this to be true. It seems to follow that the peculiarly level, lifeless, decorative effect of his narratives, which remind us rather of glorious tapestries than of pictures, was no longer wholly satisfactory to himself. There is plenty of charmed and delightful reading—“Jason” and the “Earthly Paradise” are literature for The Castle of Indolence, but we do miss a strenuous rendering of action and passion. These Mr. Morris had rendered in “The Defence of Guinevere”: now he gave us something different, something beautiful, but something deficient in dramatic vigour. Apollonius Rhodius is, no doubt, much of a pedant, a literary writer of epic, in an age of Criticism. He dealt with the tale of “Jason,” and conceivably he may have borrowed from older minstrels. But the Medea of Apollonius Rhodius, in her love, her tenderness, her regret for home, in all her maiden words and ways, is undeniably a character more living, more human, more passionate, and more sympathetic, than the Medea of Mr. Morris. I could almost wish that he had closely followed that classical original, the first true love story in literature. In the same way I prefer Apollonius’s spell for soothing the dragon, as much terser and more somniferous than the spell put by Mr. Morris into the lips of Medea. Scholars will find it pleasant to compare these passages of the Alexandrine and of the London poets. As a brick out of the vast palace of “Jason” we may select the song of the Nereid to Hylas—Mr. Morris is always happy with his Nymphs and Nereids:—

“I know a little garden-close

Set thick with lily and with rose,

Where I would wander if I might

From dewy dawn to dewy night,

And have one with me wandering.

And though within it no birds sing,

And though no pillared house is there,

And though the apple boughs are bare

Of fruit and blossom, would to God,

Her feet upon the green grass trod,

And I beheld them as before.

There comes a murmur from the shore,

And in the place two fair streams are,

Drawn from the purple hills afar,

Drawn down unto the restless sea;

The hills whose flowers ne’er fed the bee,

The shore no ship has ever seen,

Still beaten by the billows green,

Whose murmur comes unceasingly

Unto the place for which I cry.

For which I cry both day and night,

For which I let slip all delight,

That maketh me both deaf and blind,

Careless to win, unskilled to find,

And quick to lose what all men seek.

Yet tottering as I am, and weak,

Still have I left a little breath

To seek within the jaws of death

An entrance to that happy place,

To seek the unforgotten face

Once seen, once kissed, once rest from me

Anigh the murmuring of the sea.”

“Jason” is, practically, a very long tale from the “Earthly Paradise,” as the “Earthly Paradise” is an immense treasure of shorter tales in the manner of “Jason.” Mr. Morris reverted for an hour to his fourteenth century, a period when London was “clean.” This is a poetic license; many a plague found mediæval London abominably dirty! A Celt himself, no doubt, with the Celt’s proverbial way of being impossibilium cupitor, Mr. Morris was in full sympathy with his Breton Squire, who, in the reign of Edward III., sets forth to seek the Earthly Paradise, and the land where Death never comes. Much more dramatic, I venture to think, than any passage of “Jason,” is that where the dreamy seekers of dreamland, Breton and Northman, encounter the stout King Edward III., whose kingdom is of this world. Action and fantasy are met, and the wanderers explain the nature of their quest. One of them speaks of death in many a form, and of the flight from death:—

“His words nigh made me weep, but while he spoke

I noted how a mocking smile just broke

The thin line of the Prince’s lips, and he

Who carried the afore-named armoury

Puffed out his wind-beat cheeks and whistled low:

But the King smiled, and said, ‘Can it be so?

I know not, and ye twain are such as find

The things whereto old kings must needs be blind.

For you the world is wide—but not for me,

Who once had dreams of one great victory

Wherein that world lay vanquished by my throne,

And now, the victor in so many an one,

Find that in Asia Alexander died

And will not live again; the world is wide

For you I say,—for me a narrow space

Betwixt the four walls of a fighting place.

Poor man, why should I stay thee? live thy fill

Of that fair life, wherein thou seest no ill

But fear of that fair rest I hope to win

One day, when I have purged me of my sin.

Farewell, it yet may hap that I a king

Shall be remembered but by this one thing,

That on the morn before ye crossed the sea

Ye gave and took in common talk with me;

But with this ring keep memory with the morn,

O Breton, and thou Northman, by this horn

Remember me, who am of Odin’s blood.’”

All this encounter is a passage of high invention. The adventures in Anahuac are such as Bishop Erie may have achieved when he set out to find Vinland the Good, and came back no more, whether he was or was not remembered by the Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl. The tale of the wanderers was Mr. Morris’s own; all the rest are of the dateless heritage of our race, fairy tales coming to us, now “softly breathed through the flutes of the Grecians,” now told by Sagamen of Iceland. The whole performance is astonishingly equable; we move on a high tableland, where no tall peaks of Parnassus are to be climbed. Once more literature has a narrator, on the whole much more akin to Spenser than to Chaucer, Homer, or Sir Walter. Humour and action are not so prominent as contemplation of a pageant reflected in a fairy mirror. But Mr. Morris has said himself, about his poem, what I am trying to say:—

“Death have we hated, knowing not what it meant;

Life have we loved, through green leaf and through sere,

Though still the less we knew of its intent;

The Earth and Heaven through countless year on year,

Slow changing, were to us but curtains fair,

Hung round about a little room, where play

Weeping and laughter of man’s empty day.”

Mr. Morris had shown, in various ways, the strength of his sympathy with the heroic sagas of Iceland. He had rendered one into verse, in “The Earthly Paradise,” above all, “Grettir the Strong” and “The Volsunga” he had done into English prose. His next great poem was “The Story of Sigurd,” a poetic rendering of the theme which is, to the North, what the Tale of Troy is to Greece, and to all the world. Mr. Morris took the form of the story which is most archaic, and bears most birthmarks of its savage origin—the version of the “Volsunga,” not the German shape of the “Nibelungenlied.” He showed extraordinary skill, especially in making human and intelligible the story of Regin, Otter, Fafnir, and the Dwarf Andvari’s Hoard.

“It was Reidmar the Ancient begat me; and now was he waxen old,

And a covetous man and a king; and he bade, and I built him a hall,

And a golden glorious house; and thereto his sons did he call,

And he bade them be evil and wise, that his will through them might be wrought.

Then he gave unto Fafnir my brother the soul that feareth nought,

And the brow of the hardened iron, and the hand that may never fail,

And the greedy heart of a king, and the ear that hears no wail.“But next unto Otter my brother he gave the snare and the net,

And the longing to wend through the wild-wood, and wade the highways wet;

And the foot that never resteth, while aught be left alive

That hath cunning to match man’s cunning or might with his might to strive.“And to me, the least and the youngest, what gift for the slaying of ease?

Save the grief that remembers the past, and the fear that the future sees;

And the hammer and fashioning-iron, and the living coal of fire;

And the craft that createth a semblance, and fails of the heart’s desire;

And the toil that each dawning quickens, and the task that is never done;

And the heart that longeth ever, nor will look to the deed that is won.“Thus gave my father the gifts that might never be taken again;

Far worse were we now than the Gods, and but little better than men.

But yet of our ancient might one thing had we left us still:

We had craft to change our semblance, and could shift us at our will

Into bodies of the beast-kind, or fowl, or fishes cold;

For belike no fixèd semblance we had in the days of old,

Till the Gods were waxen busy, and all things their form must take

That knew of good and evil, and longed to gather and make.”

But when we turn to the passage of the éclaircissement between Sigurd and Brynhild, that most dramatic and most modern moment in the ancient tragedy, the moment where the clouds of savage fancy scatter in the light of a hopeless human love, then, I must confess, I prefer the simple, brief prose of Mr. Morris’s translation of the “Volsunga” to his rather periphrastic paraphrase. Every student of poetry may make the comparison for himself, and decide for himself whether the old or the new is better. Again, in the final fight and massacre in the hall of Atli, I cannot but prefer the Slaying of the Wooers, at the close of the “Odyssey,” or the last fight of Roland at Roncesvaux, or the prose version of the “Volsunga.” All these are the work of men who were war-smiths as well as song-smiths. Here is a passage from the “murder grim and great”:—

“So he saith in the midst of the foemen with his war-flame reared on high,

But all about and around him goes up a bitter cry

From the iron men of Atli, and the bickering of the steel

Sends a roar up to the roof-ridge, and the Niblung war-ranks reel

Behind the steadfast Gunnar: but lo, have ye seen the corn,

While yet men grind the sickle, by the wind streak overborne

When the sudden rain sweeps downward, and summer groweth black,

And the smitten wood-side roareth ’neath the driving thunder-wrack?

So before the wise-heart Hogni shrank the champions of the East

As his great voice shook the timbers in the hall of Atli’s feast,

There he smote and beheld not the smitten, and by nought were his edges stopped;

He smote and the dead were thrust from him; a hand with its shield he lopped;

There met him Atli’s marshal, and his arm at the shoulder he shred;

Three swords were upreared against him of the best of the kin of the dead;

And he struck off a head to the rightward, and his sword through a throat he thrust,

But the third stroke fell on his helm-crest, and he stooped to the ruddy dust,

And uprose as the ancient Giant, and both his hands were wet:

Red then was the world to his eyen, as his hand to the labour he set;

Swords shook and fell in his pathway, huge bodies leapt and fell;

Harsh grided shield and war-helm like the tempest-smitten bell,

And the war-cries ran together, and no man his brother knew,

And the dead men loaded the living, as he went the war-wood through;

And man ’gainst man was huddled, till no sword rose to smite,

And clear stood the glorious Hogni in an island of the fight,

And there ran a river of death ’twixt the Niblung and his foes,

And therefrom the terror of men and the wrath of the Gods arose.”

I admit that this does not affect me as does the figure of Odysseus raining his darts of doom, or the courtesy of Roland when the blinded Oliver smites him by mischance, and, indeed, the Keeping of the Stair by Umslopogaas appeals to me more vigorously as a strenuous picture of war. To be just to Mr. Morris, let us give his rendering of part of the Slaying of the Wooers, from his translation of the “Odyssey”:—

“And e’en as the word he uttered, he drew his keen sword out

Brazen, on each side shearing, and with a fearful shout

Rushed on him; but Odysseus that very while let fly

And smote him with the arrow in the breast, the pap hard by,

And drove the swift shaft to the liver, and adown to the ground fell the sword

From out of his hand, and doubled he hung above the board,

And staggered; and whirling he fell, and the meat was scattered around,

And the double cup moreover, and his forehead smote the ground;

And his heart was wrung with torment, and with both feet spurning he smote

The high-seat; and over his eyen did the cloud of darkness float.“And then it was Amphinomus, who drew his whetted sword

And fell on, making his onrush ’gainst Odysseus the glorious lord,

If perchance he might get him out-doors: but Telemachus him forewent,

And a cast of the brazen war-spear from behind him therewith sent

Amidmost of his shoulders, that drave through his breast and out,

And clattering he fell, and the earth all the breadth of his forehead smote.”

There is no need to say more of Mr. Morris’s “Odysseus.” Close to the letter of the Greek he usually keeps, but where are the surge and thunder of Homer? Apparently we must accent the penultimate in “Amphinomus” if the line is to scan. I select a passage of peaceful beauty from Book V.:—

“But all about that cavern there grew a blossoming wood,

Of alder and of poplar and of cypress savouring good;

And fowl therein wing-spreading were wont to roost and be,

For owls were there and falcons, and long-tongued crows of the sea,

And deeds of the sea they deal with and thereof they have a care

But round the hollow cavern there spread and flourished fair

A vine of garden breeding, and in its grapes was glad;

And four wells of the white water their heads together had,

And flowing on in order four ways they thence did get;

And soft were the meadows blooming with parsley and violet.

Yea, if thither indeed had come e’en one of the Deathless, e’en he

Had wondered and gladdened his heart with all that was there to see.

And there in sooth stood wondering the Flitter, the Argus-bane.

But when o’er all these matters in his soul he had marvelled amain,

Then into the wide cave went he, and Calypso, Godhead’s Grace,

Failed nowise there to know him as she looked upon his face;

For never unknown to each other are the Deathless Gods, though they

Apart from one another may be dwelling far away.

But Odysseus the mighty-hearted within he met not there,

Who on the beach sat weeping, as oft he was wont to wear

His soul with grief and groaning, and weeping; yea, and he

As the tears he was pouring downward yet gazed o’er the untilled sea.”

This is close enough to the Greek, but

“And flowing on in order four ways they thence did get”

is not precisely musical. Why is Hermes “The Flitter”? But I have often ventured to remonstrate against these archaistic peculiarities, which to some extent mar our pleasure in Mr. Morris’s translations. In his version of the rich Virgilian measure they are especially out of place. The “Æneid” is rendered with a roughness which might better befit a translation of Ennius. Thus the reader of Mr. Morris’s poetical translations has in his hands versions of almost literal closeness, and (what is extremely rare) versions of poetry by a poet. But his acquaintance with Early English and Icelandic has added to the poet a strain of the philologist, and his English in the “Odyssey,” still more in the “Æneid,” is occasionally more archaic than the Greek of 900 B.C. So at least it seems to a reader not unversed in attempts to fit the classical poets with an English rendering. But the true test is in the appreciation of the lovers of poetry in general.

To them, as to all who desire the restoration of beauty in modern life, Mr. Morris has been a benefactor almost without example. Indeed, were adequate knowledge mine, Mr. Morris’s poetry should have been criticised as only a part of the vast industry of his life in many crafts and many arts. His place in English life and literature is unique as it is honourable. He did what he desired to do—he made vast additions to simple and stainless pleasures.