Reading the First Novel

Being Mostly Reminiscences of Early Crimes and Joys

Being Mostly Reminiscences of Early Crimes and Joys

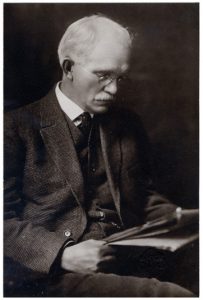

By Young E. Allison

Once more and for all, the career of a novel reader should be entered upon, if at all, under the age of fourteen. As much earlier as possible. The life of the intellect, as of its shadowy twin, imagination, begins early and develops miraculously. The inbred strains of nature lie exposed to influence as a mirror to reflections, and as open to impression as sensitized paper, upon which pictures may be printed and from which they may also fade out. The greater the variety of impressions that fall upon the young mind the more certain it is that the greatest strength of natural tendency will be touched and revealed. Good or bad, whichever it may be, let it come out as quickly as possible. How many men have never developed their fatal weaknesses until success was within reach and the edifice fell upon other innocent ones. Believe me, no innate scoundrel or brute will be much helped or hindered by stories. These have no turn or leisure for dreaming. They are eager for the actual touch of life. What would a dull-eyed glutton, famishing, not with hunger but with the cravings of digestive ferocity, find in Thackeray’s “Memorials of Gormandizing” or “Barmecidal Feasts?” Such banquets are spread for the frugal, not one of whom would swap that immortal cook-book review for a dinner with Lucullus. Rascals will not read. Men of action do not read. They look upon it as the gambler does upon the game where “no money passes.” It may almost be said that the capacity for novel-reading is the patent of just and noble minds. You never heard of a great novel-reader who was notorious as a criminal. There have been literary criminals, I grant you—Eugene Aram, Dr. Dodd, Prof. Webster, who murdered Parkmaan, and others. But they were writers, not readers. And they did not write novels. Mr. Aram wrote scientific and school books, as did Prof. Webster, and Dr. Wainwright wrote beautiful sermons. We never do sufficiently consider the evil that lies behind writing sermons. The nearest you can come to a writer of fiction who has been steeped in crime is in Benvenuto Cellini, whose marvelous autobiographical memoir certainly contains some fiction, though it is classed under the suspect department of History.

How many men actually have been saved from a criminal career by the miraculous influence of novels? Let who will deny, but at the age of six I myself was absolutely committed to the abandoned purpose of riding barebacked horses in a circus. Secretly, of course, because there were some vague speculations in the family concerning what seemed to be special adaptability to the work of preaching. Shortly after I gave that up to enlist in the Continental Army, under Gen. Francis Marion, and no other soldier slew more Britons. After discharge I at once volunteered in an Indiana regiment quartered in my native town in Kentucky, and beat the snare drum at the head of that fine body of men for a long time. But the tendency was downward. For three months I was chief of a of robbers that ravaged the backyards of the vicinity. Successively I became a spy for Washington, an Indian fighter, a tragic actor.

With character seared, abandoned and dissolute in habit through and by the hearing and seeing and reading of history, there was but one desperate step left. So I entered upon the career of a pirate in my ninth year. The Spanish Main, as no doubt you remember, was at that time upon an open common across the street from our house, and it was a hundred feet long, half as wide and would average two feet in depth. I have often since thanked Heaven that they filled up that pathless ocean in order to build an iron foundry upon the spot. Suppose they had excavated for a cellar! Why during the time that Capt. Kidd, Lafitte and I infested the coast thereabout, sailing three “low, black-hulled schooners with long rakish masts,” I forced hundreds of merchant seamen to walk the plank—even helpless women and children. Unless the sharks devoured them, their bones are yet about three feet under the floor of that iron foundry. Under the lee of the Northernmost promontory, near a rock marked with peculiar crosses made by the point of the stiletto which I constantly carried in my red silk sash, I buried tons of plate, and doubloons, pieces of eight, pistoles, Louis d’ors, and galleons by the chest. At that time galleons somehow meant to me money pieces in use, though since then the name has been given to a species of boat. The rich brocades, Damascus and Indian stuffs, laces, mantles, shawls and finery were piled in riotous profusion in our cave where—let the whole truth be told if it must—I lived with a bold, black-eyed and coquettish Spanish girl, who loved me with ungovernable jealousy that occasionally led to bitter and terrible scenes of rage and despair. At last when I brought home a white and red English girl whose life I spared because she had begged me her knees by the memory of my sainted mother to spare her for her old father, who was waiting her coming, Joquita passed all bounds. I killed her—with a single knife thrust I remember. She was buried right on the spot where the Tilden and Hendricks flag pole afterwards stood in the campaign of 1876. It was with bitter melancholy that I fancied the red stripes on the flag had their color from the blood of the poor, foolish jealous girl below.

* * * * *

Ah, well—

Let us all own up—we men of above forty who aspire to respectability and do actually live orderly lives and achieve even the odor of sanctity—have we not been stained with murder?–aye worse! What man has not his Bluebeard closet, full of early crimes and villainies? A certain boy in whom I take a particular interest, who goes to Sunday-school and whose life is outwardly proper—is he not now on week days a robber of great renown? A week ago, masked and armed, he held up his own father in a secluded corner of the library and relieved the old man of swag of a value beyond the dreams—not of avarice, but—of successful, respectable, modern speculation. He purposes to be a pirate whenever there is a convenient sheet of water near the house. God speed him. Better a pirate at six than at sixty.

Give them work to do and good novels to read and they will get over it. History breeds queer ideas in children. They read of military heroes, kings and statesmen who commit awful deeds and are yet monuments of public honor. What a sweet hero is Raleigh, who was a farmer of piracy; what a grand Admiral was Drake; what demi-gods the fighting Americans who murdered Indians for the crime of wanting their own! History hath charms to move an infant breast to savagery. Good strong novels are the best pabulum to nourish difference between virtue and vice.

Don’t I know? I have felt the miracle and learned the difference so well that even now at an advanced age I can tell the difference and indulge in either. It was not a week after the killing of Joquita that I read the first novel of my life. It was “Scottish Chiefs.” The dead bodies of ten thousand novels lie between me and that first one. I have not read it since. Ten Incas of Peru with ten rooms full of solid gold could not tempt me to read it again. Have I not a clear cinch on a delicious memory, compared with which gold is only Robinson Crusoe’s “drug?” After a lapse of all these years the content of that one tremendous, noble chapter of heroic climax is as deeply burned into my memory as if it had been read yesterday.

A sister, old enough to receive “beaux” and addicted to the piano-forte accomplishment, was at that time practicing across the hall an instrumental composition, entitled, “La Rève.” Under the title, printed in very small letters, was the English translation; but I never thought to look at it. An elocutionist had shortly before recited Poe’s Raven at a church entertainment, and that gloomy bird flapped its wings in my young emotional vicinity when the firelight threw vague “shadows on the floor.” When the piece of music was spoken as “La Rève,” its sad cadences, suffering, of course, under practice, were instantly wedded in my mind to Mr. Poe’s wonderful bird and for years it meant the “Raven” to me. How curious are childish impressions. Years afterward when I saw a copy of the music and read the translation, “The Dream” under the title, I felt a distinct shock of resentment as if the French language had been treacherous to my sacred ideas. Then there was the romantic name of “Ellerslie,” which, notwithstanding considerable precocity in reading and spelling I carried off as “Elleressie” Yeas afterward when the actual syllables confronted me in a historical sketch of Wallace, the truth entered like a stab and I closed the book. O sacred first illusions of childhood, you are sweeter than a thousand year of fame! It is God’s providence that hardens us to endure the throwing of them down to our eyes and strengthens us to keep their memory sweet in our hearts.

* * * * *

It would be an affront then, not to assume that every reputable novel reader has read “Scottish Chiefs.” If there is any descendant or any personal friend of that admirable lady, Miss Jane Porter, who may now be in pecuniary distress, let that descendant call upon me privately with perfect confidence. There are obligations that a glacial evolutionary period can not lessen. I make no conditions but the simple proof of proper identity. I am not rich but I am grateful.

It was a Saturday evening when I became aware, as by prescience, that there hung over Sir William Wallice and Helen Mar some terrible shadow of fate. And the piano-forte across the hall played “La Rève.” My heart failed me and I closed the book. If you can’t do that, my friend, then you waste your time trying to be a novel reader. You have not the true touch of genius for it. It is the miracle of eating your cake and having it, too. It must have been the unconscious moving of novel reading genius in me. For I forgot, as clearly as if it were not a possibility, that the next day was Sunday. And so hurried off, before time, to bed, to be alone with the burden on my heart.

“Backward, turn backward, O Time in your flight—

Make me a child again just for tonight.”

There are two or three novels I should love to take to bed as of yore—not to read, but to suffer over and to contemplate and to seek calmness and courage with which to face the inevitable. Could there be men base enough to do to death the noble Wallace? Or to break the heart of Helen Mar with grief? No argument could remove the presentiment, but facing the matter gave courage. “Let tomorrow answer,” I thought, as the piano-forte in the next room played “La Rève.” Then fell asleep.

And when I awoke next morning to the full knowledge that it was Sunday, I could have murdered the calendar. For Sunday was Dies Irae. After Sunday-school, at least. There is a certain amount of fun to be to extracted from Sunday-school. The remainder of those early Sundays was confined to reading the Bible or storybooks from the Sunday-school library—books, by the Lord Harry, that seem to be contrived especially to make out of healthy children life-long enemies of the church, and to bind hypocrites to the altar with hooks of steel. There was no whistling at all permitted; singing of hymns was encouraged; no “playing”—playing on Sunday was a distinct source of displeasure to Heaven! Are free-born men nine years of age to endure such tyranny with resignation? Ask the kids of today—and with one voice, as true men and free, they will answer you, “Nit!” In the dark days of my youth liberty was in chains, and so Sunday was passed in dreadful suspense as to what was doing in Scotland.

* * * * *

Monday night after supper I rejoined Sir William in his captivity and soon saw that my worst fears were to be realized. My father sat on the opposite side of the table reading politics; my mother was effecting the restoration of socks; my brother was engaged in unraveling mathematical tangles, and in the parlor across the hall my sister sat alone with her piano patiently debating “La Rève.” Under these circumstances I encountered the first great miracle of intellectual emotion in the chapter describing the execution of William Wallace on Tower Hill. No other incident of life has left upon me such a profound impression. It was as if I had sprung at one bound into the arena of heroism. I remember it all. How Wallace delivered himself of theological and Christian precepts to Helen Mar after which they both knelt before the officiating priest. That she thought or said, “My life will expire with yours!” It was the keynote of death and life devotion. It was worthy to usher Wallace up the scaffold steps where he stood with his hands bound, “his noble head uncovered.” There was much Christian edification, but the presence of such a hero as he with “noble Head uncovered” would enable any man nine years old with a spark of honor and sympathy in him to endure agonizing amounts of edification. Then suddenly there was a frightful shudder in my heart. The hangman approached with the rope, and Helen Mar, with a shriek, threw herself upon Wallace’s breast. Then the great moment. If I live a thousand years these lines will always be with me: “Wallace, with a mighty strength, burst the bonds asunder that confined his arms and clasped her to his heart!”

* * * * *

In reading some critical or pretended text books on construction since that time I came across this sentence used to illustrate tautology. It was pointed out that the bonds couldn’t be “burst” without necessarily being asunder. The confoundedest outrages in this world are the capers that precisionists cut upon the bodies of the noble dead. And with impunity too. Think of a village surveyor measuring the forest of Arden to discover the exact acreage! Or a horse-doctor elevating his eye-brow with a contemptuous smile and turning away, as from an innocent, when you speak of the wings of that fine horse, Pegasus! Any idiot knows that bonds couldn’t be burst without being burst asunder. But, let the impregnable Jackass think—what would become of the noble rhythm and the majestic roll of sound? Shakespeare was an ignorant dunce also when he characterized the ingratitude that involves the principle of public honor as “the unkindest cut of all.” Every school child knows that it is ungrammatical; but only those who have any sense learn after awhile the esoteric secret that it sometimes requires a tragedy of language to provide fitting sacrifice to the manes of despair. There never was yet a man of genius who wrote grammatically and under the scourge of rhetorical rules. Anthony Trollope is a most perfect example of the exact correctness that sterilizes in its own immaculate chastity. Thackeray would knock a qualifying adverb across the street, or thrust it under your nose to make room for the vivid force of an idea. Trollope would give the idea a decent funeral for the sake of having his adverb appear at the grave above reproach from grammatical gossip. Whenever I have risen from the splendid psychological perspective of old Job, the solemn introspective howls of Ecclesiasticus and the generous living philosophy of Shakespeare it has always been with the desire—of course it is undignified, but it is human—to go and get an English grammar for the pleasure of spitting upon it. Let us be honest. I understand everything about grammar except what it means; but if you will give me the living substance and the proper spirit any gentleman who desires the grammatical rules may have them, and be hanged to him! And, while it may appear presumptuous, I can conscientiously say that it will not be agreeable to me to settle down in heaven with a class of persons who demand the rules of grammar for the intellectual reason that corresponds to the call for crutches by one-legged men.

* * * * *

If the foregoing appear ill-tempered pray forget it. Remember rather that I have sought to leave my friend Sir William Wallace, holding Helen Mar on his breast as long as possible. And yet, I also loved her! Can human nature go farther than that?

“Helen,” he said to her, “life’s cord is cut by God’s own hand.” He stooped, he fell, and the fall shook the scaffold. Helen—that glorified heroine—raised his head to her lap. The noble Earl of Gloucester stepped forward, took the head in his hands.

“There,” he cried in a burst of grief, letting it fall again upon the insensible bosom of Helen, “there broke the noblest heart that ever beat in the breast of man!”

That page or two of description I read with difficulty and agony through blinding tears, and when Gloucester spoke his splendid eulogy my head fell on the table and I broke into such wild sobbing that the little family sprang up in astonishment. I could not explain until my mother, having led me to my room, succeeded in soothing me into calmness and I told her the cause of it. And she saw me to bed with sympathetic caresses and, after she left, it all broke out afresh and I cried myself to sleep in utter desolation and wretchedness. Of course the matter got out and my father began the book. He was sixty years old, not an indiscriminate reader, but a man of kind and boyish heart. I felt a sort of fascinated curiosity to watch him when he reached the chapter that had broken me. And, as if it were yesterday, I can see him under the lamplight compressing his lips, or puffing like a smoker through them, taking off his spectacles, and blowing his nose with great ceremony and carelessly allowing the handkerchief to reach his eyes. Then another paragraph and he would complain of the glasses and wipe them carefully, also his eyes, and replace the spectacles. But he never looked at me, and when he suddenly banged the lids together and, turning away, sat staring into the fire with his head bent forward, making unconcealed use of the handkerchief, I felt a sudden sympathy for him and sneaked out. He would have made a great novel reader if he had had the heart. But he couldn’t stand sorrow and pain. The novel reader must have a heart for every fate. For a week or more I read that great chapter and its approaches over and over, weeping less and less, until I had worn out that first grief, and could look with dry eyes upon my dead. And never since have I dared to return to it. Let who will speak freely in other tones of “Scottish Chiefs”—opinions are sacred liberties—but as for me I know it changed my career from one of ruthless piracy to better purposes, and certain boys of my private acquaintance are introduced to Miss Jane Porter as soon as they show similar bent.