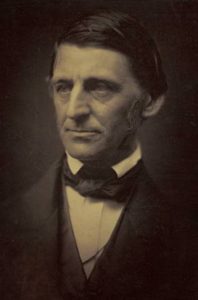

Ralph Waldo Emerson

EMERSON, RALPH WALDO (1803-1882). —Philosopher, was born at Boston, Massachusetts. His father was a minister there, who had become a Unitarian, and who died in 1811, leaving a widow with six children, of whom Ralph, then aged 8, was the second. Mrs. Emerson was, however, a woman of energy, and by means of taking boarders managed to give all her sons a good education. Emerson entered Harvard in 1817 and, after passing through the usual course there, studied for the ministry, to which he was ordained in 1827, and settled over a congregation in his native city. There he remained until 1832, when he resigned, ostensibly on a difference of opinion with his brethren on the permanent nature of the Lord’s Supper as a rite, but really on a radical change of view in regard to religion in general, expressed in the maxim that “the day of formal religion is past.” About the same time he lost his young wife, and his health, which had never been robust, showed signs of failing. In search of recovery he visited Europe, where he met many eminent men and formed a life-long friendship with Carlyle. On his return in 1834 he settled at Concord, and took up lecturing. In 1836 he published Nature, a somewhat transcendental little book which, though containing much fine thought, did not appeal to a wide circle. The American Scholar followed in 1837.

EMERSON, RALPH WALDO (1803-1882). —Philosopher, was born at Boston, Massachusetts. His father was a minister there, who had become a Unitarian, and who died in 1811, leaving a widow with six children, of whom Ralph, then aged 8, was the second. Mrs. Emerson was, however, a woman of energy, and by means of taking boarders managed to give all her sons a good education. Emerson entered Harvard in 1817 and, after passing through the usual course there, studied for the ministry, to which he was ordained in 1827, and settled over a congregation in his native city. There he remained until 1832, when he resigned, ostensibly on a difference of opinion with his brethren on the permanent nature of the Lord’s Supper as a rite, but really on a radical change of view in regard to religion in general, expressed in the maxim that “the day of formal religion is past.” About the same time he lost his young wife, and his health, which had never been robust, showed signs of failing. In search of recovery he visited Europe, where he met many eminent men and formed a life-long friendship with Carlyle. On his return in 1834 he settled at Concord, and took up lecturing. In 1836 he published Nature, a somewhat transcendental little book which, though containing much fine thought, did not appeal to a wide circle. The American Scholar followed in 1837.

Two years previously he had entered into a second marriage. His influence as a thinker rapidly extended, he was regarded as the leader of the transcendentalists, and was one of the chief contributors to their organ, The Dial. The remainder of his life, though happy, busy, and influential, was singularly uneventful. In 1847 he paid a second visit to England, when he spent a week with Carlyle, and delivered a course of lectures in England and Scotland on “Representative Men,” which he subsequently pub. English Traits appeared in 1856. In 1857 The Atlantic Monthly was started, and to it he became a frequent contributor. In 1874 he was nominated for the Lord Rectorship of the Univ. of Glasgow, but was defeated by Disraeli. He, however, regarded his nomination as the greatest honour of his life. After 1867 he wrote little. He d. on April 27, 1882. His works were collected in 11 vols., and in addition to those above mentioned include Essays (two series), Conduct of Life, Society and Solitude, Natural History of Intellect, and Poems. The intellect of Emerson was subtle rather than robust, and suggestive rather than systematic. He wrote down the intuitions and suggestions of the moment, and was entirely careless as to whether these harmonised with previous statements. He was an original and stimulating thinker and writer, and wielded a style of much beauty and fascination. His religious views approached more nearly to Pantheism than to any other known system of belief. He was a man of singular elevation and purity of character.

*******

See also: Self-Reliance, an essay by Emerson