The All-America Period

[This is taken from William J. Long’s Outlines of English and American Literature.]

[This is taken from William J. Long’s Outlines of English and American Literature.]

Thou Mother with thy equal brood,

Thou varied chain of different States, yet one identity only,

A special song before I go I’d sing o’er all the rest:

For thee, the Future.

Whitman, “Thou Mother”

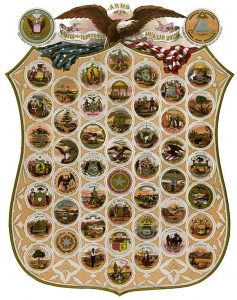

Some critics find little or no American literature of a distinctly national spirit prior to 1876, and they explain the lack of it on the assumption that Americans were too far apart and too much occupied with local or sectional interests for any author to represent the nation. It was even said at the time of the Centennial Exposition that our countrymen had never met, save on the battlefields of the Civil War, until the common interest in Jubilee Year drew men and women from the four quarters of America “around the old family altar at Philadelphia.” Whatever exaggeration there may be in that fine poetic figure, it is certain that our literature, once confined to a few schools or centers, began in the decade after 1870 to be broadly representative of the whole country. Miller’s Songs of the Sierras, Hay’s Pike-County Ballads, Harte’s Tales of the Argonauts, Cable’s Old Creole Days, Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer, Miss Jewett’s Deephaven, Stockton’s Rudder Grange, Harris’s Uncle Remus,–a host of surprising books suddenly appeared with the announcement that America was too large for any one man or literary school to be its spokesman. It is because of these new voices, coming from North, South, East or West and heard with delight by the whole nation, that we venture to call the years after 1876 the all-America period of our literature.

We are still too near that period to make a history of it, for the simple reason that a true history implies distance and perspective. No historian could read, much less measure and compare, a tenth part of the books that have won recognition since 1876. In such works as he might select as typical he must be governed by his own taste or judgment; and the writer was never born who could by such personal standards forecast the judgment of time and of humanity. In a word, contemporary or “up-to-date” histories are vain attempts at the impossible; save in the unimportant matter of chronicling names or dates they are all alike untrustworthy. The student should bear in mind, therefore, that the following summary of our recent literature is based largely upon personal opinion; that it selects a few authors by way of illustration, omitting many others who may be of equal or greater importance. We are confronted by a host of books that serve the prime purpose of literature by giving pleasure; but what proportion of them are enduring books, or what few of them will be known to readers of the next century as the Sketch Book and Snow-Bound are known to us,–these are questions that only Father Time can answer.

THE SHORT STORY. The period after 1876 has been called the age of fiction, but “the short-story age” might be a better name for it, since the short story is apparently more popular than any other form of literature and since it has been developed here more abundantly than in any other land,–possibly because America offers such an immense and ever-surprising field to an author in search of a strange or picturesque tale. Readers of the short story demand life and variety, and here are all races and tribes and conditions of men, living in all kinds of “atmosphere” from the trapper’s hut to the steel skyscraper and from the crowded city slums to the vast open places where one’s companionship is with the hills or the stars. Hence a double tendency in our recent stories, to make them expressive of New World life and to make each story a reflection of some peculiar type of Americanism,–one of the many types that here meet in a common citizenship.

The truth of the above criticism may become evident by reviewing the history of the short story in America. Irving began with mere hints or outlines of stories (sketches he called them) and added a few legendary tales of the Dutch settlers on the Hudson. Then came Poe, dealing with the phantoms of his own brain rather than with human life or endeavor. Next appeared Hawthorne, who dealt largely in moral allegories and whose tales are always told in an atmosphere of mystery and twilight shadows. Finally, after the war, came a multitude of writers who insisted on dealing with our American life as it is, with miners, immigrants, money kings, mountaineers, planters, cowboys, woodsmen,–a host of varied characters, each speaking the speech and typifying the customs or ideals of his particular locality. It was these post-bellum writers who invented the so-called story of local color (a story true to a certain place or a certain class of men), which is America’s most original contribution to the world’s literature.

Francis Bret Harte (1839-1902) is generally credited with the invention of the local-color story; but he was probably indebted to earlier works of the same kind, notably to Longstreet’s Georgia Scenes (1836) and Baldwin’s Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi (1853). He had followed the “forty-niners” to California in a headlong search for gold when, finding himself amid the picturesque scenes and characters of the early mining camps, it suddenly occurred to him that he had before his eyes a literary gold mine such as no other modern romancer had discovered. Thereupon he wrote “The Luck of Roaring Camp” (first published in The Overland Monthly, 1868), and followed it with “The Outcasts of Poker Flat” and “Tennessee’s Partner.”

These stories took the literary world by storm, and almost overnight Harte became a celebrity. Following up his advantage he proceeded to write some thirty volumes of the same general kind, which were widely read and promptly forgotten. Though he was plainly too sentimental and sensational, there was a sense of freshness or originality in his early stories and poems which made them wonderfully attractive. His first three tales were probably his best, and they are still worth reading,–not for their literary charm or truth but as interesting early examples of the local-color story.

The interest aroused by the mining-camp tales influenced other American writers to discover the neglected literary wealth of their several localities; but they were fortunately on guard against Harte’s exaggerated sentimentality and related their stories with more art and more truth to nature. As a specific example read Cable’s Old Creole Days and Madame Delphine with their exquisite pictures of life in the old French city of New Orleans. These are romances or creations of fancy, to be sure; but in their lifelike characters, their natural scenes and soft Creole dialect they are as realistic (that is, as true to a real type of American life) as anything that can be found in literature. They are, in fact, studies as well as stories, such minute and affectionate studies of old people, old names and old customs as the great French novelist Balzac made in preparation for his work. Though time holds its own secrets, one can hardly avoid the conviction that Old Creole Days and Madame Delphine are not books of a day but permanent additions to American fiction.

Cable was accompanied by so many other good writers that it would require a volume to do them justice. We name only, by way of indicating the wide variety that awaits the reader, the charming stories of Grace King and writers Kate Chopin dealing with plantation life; the New England stories, powerful or brilliant or somber, of Sarah Orne Jewett, Rose Terry Cooke and Mary E. Wilkins; the tender and cheery southern stories of Thomas Nelson Page; the impressive stories of mountaineer life by Mary Noailles Murfree (Charles Egbert Craddock); the humorous, Alice-in-Wonderland kind of stories told by Frank Stockton; and a bewildering miscellany of other works, of which the names Thomas Bailey Aldrich, Hamlin Garland, Alice French (Octave Thanet), Rowland Robinson, Frank Norris and Henry C. Bunner are as a brief but inviting index.

It would be unjust at the present time to discriminate among these writers or to compare them with others, perhaps equally good, whom we have not named. Occasionally in the flood of short stories appears one that compels attention. Aldrich’s “Marjorie Daw,” Edward Everett Hale’s “The Man without a Country,” Stockton’s “The Lady or the Tiger,”—each of these impresses us so forcibly by its delicate artistry or appeal to patriotism or whimsical ending that we hail it as a new classic, forgetting that the term “classic” carries with it the implication of something old and proved, safe from change or criticism. Undoubtedly a few of our recent stories deserve the name; they will be more widely known a century hence than they are now, and may finally rank above “Rip Van Winkle” or “The Gold Bug” or “The Snow Image”; but until the perfect tale is sifted from the thousand that are almost perfect, every ambitious critic is free to make his own prophecy.

SOME RECENT NOVELISTS. There is a difference between our earlier and later fiction which becomes apparent when we compare specific examples. As a type of the earlier novel take Cooper’s The Spy or Longfellow’s Hyperion or Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables or Simms’s Katherine Walton or Cooke’s The Virginia Comedians, and read it in connection with a recent novel, such as Howells’s Annie Kilburn or Miss Jewett’s Deephaven or Harold Frederick’s Illumination or James Lane Allen’s The Reign of Law or Frank Norris’s The Octopus. Disregarding the important element of style, we note that the earlier novels have a distant background in time or space; that their chief interest lies in the story they have to tell; that they take us far away from present reality into regions where people are more impressive and sentiments more exalted than in our familiar, prosaic world. The later novels interest us less by the story than by the analysis of character; they deal with human life as it is here and now, not as we imagine it to have been elsewhere or in a golden age. In a word, our later novels are realistic in purpose, and in this respect they are in marked contrast with our novels of an earlier age, which are nearly all of the romantic kind.

The realistic movement in American fiction began, as we have noted, with the short-story writers; and presently the most talented of these writers, having learned the value of real scenes and characters, turned to the novel and produced works having the double interest of romance and realism; that is, they told an old romantic tale of love or heroism and set it amid scenes or characters that were typical of American life. Miss Jewett’s novels of northern village life, for example, are even finer than her short stories in the same field. The same criticism applies to Miss Murfree with her novels of mountaineer life in Tennessee, to James Lane Allen with his novels of his native Kentucky, and to many another recent novelist who tells a brave tale of his own people. We call these, in the conventional way, novels of New England or the South or the West; in reality they are novels of humanity, of the old unchanging tragedies or comedies of human life, which seem more true or real to us because they appear in a familiar setting.

There is another school of realism which subordinates the story element, which avoids as untrue all unusual or heroic incidents and deals with ordinary men or women; and of this school William Dean Howells is a conspicuous example. Judging him by his novels alone it would be difficult to determine his rank; but judging him by his high aim and distinguished style (a style remarkable for its charm and purity in an age too much influenced by newspaper slang and smartness) he is certainly one of the best of our recent prose writers. Since his first modest volume appeared in 1860 he has published many poems, sketches of travel, appreciations of literature, parlor comedies, novels,–an immense variety of writings; but whatever one reads of his sixty-odd books, whether Venetian Life or A Boys’ Town, one has the impression of an author who lives for literature, who puts forth no hasty or unworthy work, and who aims steadily to be true to the best traditions of American letters.

In middle life Howells turned definitely to fiction and wrote, among various other novels, A Woman’s Reason, The Minister’s Charge, A Modern Instance and The Rise of Silas Lapham. These are all realistic in that they deal frankly with contemporary life; but in their plots and conventional endings they differ but little from the typical romance. [Footnote: Several of Howells’s earlier novels deal with New England life, but superficially and without understanding. However minutely they depict its manners or mannerisms they seldom dip beneath the surface. If the reader wants not the body but the soul of New England, he must go to some other fiction writer, to Sarah Orne Jewett, for example, or to Rose Terry Cooke] Then Howells fell under the influence of Tolstoi and other European realists, and his later novels, such as Annie Kilburn, A Hazard of New Fortunes and The Quality of Mercy, are rather aimless studies of the speech, dress, mannerisms and inanities of American life with precious little of its ideals,–which are the only things of consequence, since they alone endure. He appears here as the photographer rather than the painter of American life, and his work has the limited interest of another person’s family album.

Another realist of a very different kind is Samuel L. Clemens (1835-1910), who is more widely known by his pseudonym of Mark Twain. He grew up, he tells us, in “a loafing, down-at-the-heels town in Missouri”; he was educated “on the river,” and in most of his work he attempted to deal with the rough-and-ready life which he knew intimately at first hand. His Life on the Mississippi, a vivid delineation of river scenes and characters, is perhaps his best work, or at least the most true to his aim and his experience. Roughing It is another volume from his store of personal observation, this time in the western mining camps; but here his realism goes as far astray from truth as any old romance in that it exaggerates even the sensational elements of frontier life.

The remaining works of Mark Twain are, with one or two exceptions, of very doubtful value. Their great popularity for a time was due largely to the author’s reputation as a humorist,–a strange reputation it begins to appear, for he was at heart a pessimist, an iconoclast, a thrower of stones, and with the exception of his earliest work, The Celebrated Jumping Frog (1867), which reflected some rough fun or horseplay, it is questionable whether the term “humorous” can properly be applied to any of his books. Thus the blatant Innocents Abroad is not a work of humor but of ridicule (a very different matter), which jeers at travelers who profess admiration for the scenery or institutions of Europe,–an admiration that was a sham to Mark Twain because he was incapable of understanding it. So with the grotesque capers of A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court, with the sneering spirit of The Man that Corrupted Hadleyburg, with the labored attempts to be funny of Adam’s Diary and with other alleged humorous works; readers of the next generation may ask not what we found to amuse us in such works but how we could tolerate such crudity or cynicism or bad taste in the name of American humor.

The most widely read of Mark Twain’s works are Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. The former, a glorification of a liar and his dime-novel adventures, has enough descriptive power to make the story readable, but hardly enough to disguise its sensationalism, its lawlessness, its false standards of boy life and American life. In Huckleberry Finn, a much better book, the author depicts the life of the Middle West as seen by a homeless vagabond. With a runaway slave as a companion the hero, Huck Finn, drifts down the Mississippi on a raft, meeting with startling experiences at the hands of quacks and imposters of every kind. One might suppose, if one took this picaresque record seriously, that a large section of our country was peopled wholly by knaves and fools. The adventures are again of a sensational kind; but the characters are powerfully drawn, and the vivid pictures of the mighty river by day or night are among the best examples of descriptive writing in our literature.

Still another type of realism is suggested by the names Stephen Crane and Frank Norris. These young writers, influenced by the French novelist Zola, condemned the old romance as false and proclaimed, somewhat grandly at first, that they would tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Then they straightway forgot that health and moral sanity are the truth of life, and proceeded to deal with degraded or degenerate characters as if these were typical of humanity. Their earlier works are studies of brutality, miscalled realism; but later Crane wrote his Red Badge of Courage (a rather wildly imaginative story of the Civil War), and Norris produced works of real power in The Octopus and The Pit, one a prose epic of the railroad, the other of a grain of wheat from the time it is sown in the ground until it becomes a matter of good food or of crazy speculation. There is an impression of vastness, of continental breadth and sweep, in these two novels which sets them apart from all other fiction of the period.

The flood of dialect stories which appeared after 1876 may seem at first glance to be mere variations of Bret Harte’s local-color stories, but they are something more and better than that. The best of them—such, for example, as Page’s In Ole Virginia or Rowland Robinson’s Danvis Folk–are written on the assumption that we can never understand a man, that is, the soul of a man, unless we know the very language in which he expresses his thought or feeling. These dialect stories, therefore, are intimate studies of American life rather than of local speech or manners.

Joel Chandler Harris (1848-1908) is not our best writer of dialect stories but only the happy and most fortunate man who wrote Uncle Remus (1880), and wrote it, by the way, as part of his day’s work as a newspaper man, without a thought that it was a masterpiece, a work of genius. The first charm of the book is that it fascinates children with its frolicsome adventures of Brer Rabbit, Brer Tarrypin, Brer B’ar, Brer Fox and the wonderful Tar Baby; the second, that it combines in a remarkable way a primitive or universal with a local and intensely human interest. Thus, almost everybody is interested in folklore, especially in the animal stories which are part of the tradition of every primitive tribe; but folklore, as commonly written, is not a branch of fiction but of science. Before it can enter the golden door of literature it must find or create some human character who interests us not by his stories but by his humanity; and Harris furnished this character in the person of Uncle Remus, a very lovable old plantation negro, drawn with absolute fidelity to life.

Other novelists have portrayed a negro in fiction, but Harris did a more original work by creating his Brer Rabbit. In the adventures of this happy-go-lucky creature, with his childishness and humor, we have the symbol not of any one negro but of the whole race of negroes as the author knew them intimately in a condition of servitude. The creation of these two original characters, as real as Poor Richard or Natty Bumppo and far more fascinating, is one of the most notable achievements of American fiction.

Aside from the realistic movement, our recent fiction is like a river flowing sluggishly over hidden bowlders: the surface is so broken by whirlpools, eddies and aimless flotsam that it is difficult to determine the main current. Here our attention is attracted by clever stories of “society in the making,” there by somber problem-novels dealing with city slums, lonely farms, department stores, political rings, business corruption, religious creeds, social injustice,–with every conceivable matter that can furnish a novelist not with a story but with a cry for reform. The propaganda novel is evidently a favorite in America; but whether it has any real influence in reforming abuses, as the novels of Dickens led to better schools and prisons in England, is yet to be determined.

Occasionally appears a reform novel great enough to make us forget the reform, such as Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona (1884). This famous story began as an attempt to plead the cause of the oppressed Indian, to do for him what Uncle Tom’s Cabin was supposed to have done for the negro; it ended in an idyllic story so well told that readers forgot to cry, “Lo, the poor Indian,” as the author intended. At the present time Ramona is not classed with the problem-novels but with the most readable of American romances.

While the new realistic novel occupied the attention of critics the old romance had, as usual, an immensely larger number of readers. Moral romances with a happy ending have always been popular, and of these E. P. Roe furnished an abundance. His Barriers Burned Away, A Face Illumined, Opening of a Chestnut Burr and Nature’s Serial Story depict American characters in an American landscape, and have a wholesome atmosphere of manliness and cleanness that makes them eminently “safe” reading. Unfortunately they are melodramatic and sentimental, and critics commonly sneer or jeer at them; but that is not a rational criticism. Romances that won instant welcome from a host of readers and that are still widely known after half a century have at least “the power to live”; and vitality, the quality that makes a character or a story endure, is always one of the marks of a good romance.

Another romancer untouched by the zeal for realism was Marion Crawford, who in a very interesting essay, The Novel, proclaimed with some show of reason that the novel was simply a “pocket theater,” a convenient stage whereon the reader could enjoy by himself any comedy or tragedy that pleased him. That Crawford lived abroad the greater part of his life and was familiar with society in a dozen countries may explain the fact that his forty-odd novels are nearly all of the social kind. His Roman novels, Saracinesca, Sant’ Ilario and a dozen others, are perhaps his best work. They are good stories; they take us among cultured foreign people and give us glimpses of a life that is hidden from most travelers; but they are superficial and leave the impression that the author was a man without much heart, that he missed the deeper meanings of life because he had little interest in them. His characters are as puppets that are sent through a play for our amusement and for no other reason. In this, however, he remained steadily true to his own ideal of fiction as a convenient substitute for the theater. Moreover, he was a good workman; his stories were for the most part well composed and very well written.

More popular even than the romances of Roe and Crawford are the stories with a background of Colonial or Revolutionary history, a type to which America has ever given hearty welcome. Ford’s Janice Meredith, Mitchell’s Hugh Wynne, Mary Johnston’s To Have and to Hold, Maurice Thompson’s Alice of Old Vincennes, Churchill’s Richard Carvel,–the reader can add to the list of recent historical romances almost indefinitely; but no critic can now declare which shall be called great among them. To the same interesting group of writers belong Lew Wallace, whose enormously popular Ben Hur has obscured his better story, The Fair God, and Mary Hartwell Catherwood, whose Lady of Fort St. John and other stirring tales of the Northwest have the same savage wilderness background against which Parkman wrote his histories.

For other romances of the period we have no convenient term except to call them old-fashioned. Such, for instance, are Blanche Willis Howard’s One Summer and Arthur Sherburne Hardy’s Passe Rose and But Yet a Woman,–pleasant, leisurely, exquisitely finished romances, which belong to no particular time or place and which deserve the fine old name of romance, because they seem to grow young rather than old with the passing years.

POETRY SINCE 1876. It is commonly assumed that the last half century has been almost exclusively an age of prose. The student of literature knows, on the contrary, that one difficulty of judging our recent poetry lies in the amount and variety of it. Since 1876 more poetry has been published here than in all the previous years of our history; and the quality of it, if one dare judge it as a whole, is surprisingly good. The designation of “the prose age,” therefore, should not blind us to the fact that America never had so many poets as at present. Whether a future generation will rank any of these among our elder poets is another question. Of late years we have had no singer to compare with Longfellow, to be sure; but we have had a dozen singers who reflect the enlarging life of America in a way of which Longfellow never dreamed. He lived mostly in the past and was busy with legends, folklore, songs of the night; our later singers live in the present and write songs of the day. And this suggests the chief characteristic of recent poetry; namely, that it aims to be true to life as it is here and now rather than to life as it was romantically supposed to be in classic or medieval times. [Footnote: The above characterization applies only to the best, or to what most critics deem best, of our recent poetry. It takes no account of a large mass of verse which leaves an impression of faddishness in the matter of form or phrase or subject. Such verse appeals to the taste of the moment, but Time has an effective way of dealing with it and with all other insincerities in literature.]

This emancipation of our poetry from the past, with the loss and gain which such a change implies, was not easily accomplished, and the terrible reality of the great war was perhaps the decisive factor in the struggle. Before the war our poetry was largely conventional, imitative, sentimental; and even after the war, when Miller’s Songs of the Sierras and John Hay’s Pike-County Ballads began to sing, however crudely, of vigorous life, the acknowledged poets and critics of the time were scandalized. Thus, to read the letters of Bayard Taylor is to meet a poet who bewails the lack of poetic material in America and who “hungers,” as he says, for the romance and beauty of other lands. He writes Songs of the Orient, Lars: a Pastoral of Norway, Prince Deukalion and many other volumes which seem to indicate that poetry is to be found everywhere save at home. Even his “Song of the Camp” is located in the Crimea, as if heroism and tenderness had not recently bloomed on a hundred southern battlefields. So also Stedman wrote his Alectryon and The Blameless Prince, and Aldrich spent his best years in making artificial nosegays (as Holmes told him frankly) when he ought to have been making poems. These and many other poets said proudly that they belonged to the classic school; they all read Shelley and Keats, dreamed of medieval or classic beauty, and in unnumbered reviews condemned the crudity of those who were trying to find beauty at their own doors and to make poetry of the stuff of American life.

It was the war, or rather the new American spirit that issued from the war, which finally assured these poets and critics that mythology and legend were, so far as America was concerned, as dead as the mastodon, and that life itself was the only vitally interesting subject of poetry. Edmund Clarence Stedman (1833-1908), after writing many “finished” poems that were praised and forgotten, manfully acknowledged that he had been following the wrong trail and turned at last to the poetry of his own people. His Alice of Monmouth, an idyl of the war, and a few short pieces, such as “Wanted: a Man,” are the only parts of his poetical works that are now remembered. Thomas Bailey Aldrich (1836-1907) went through the same transformation. He had a love of formal beauty, and in the exquisite finish of his verse has had few rivals in American poetry; but he spent the great part of his life in making pretty trifles. Then he seemed to waken to the meaning of poetry as a noble expression of the truth or beauty of this present life, and his last little book of Songs and Sonnets contains practically all that is worth remembering of his eight or nine volumes of verse.

One of the first in time of the new singers was Cincinnatus Heine Miller or, as he is commonly known, Joaquin Miller (1841-1912). His Songs of the Sierras (1871) and other poems of the West have this advantage, that they come straight from the heart of a man who has shared the stirring life he describes and who loves it with an overmastering love. To read his My Own Story or the preface to his Ship in the Desert is to understand from what fullness of life came lines like these:

Room! room to turn round in, to breathe and be free,

To grow to be giant, to sail as at sea

With the speed of the wind on a steed with his mane

To the wind, without pathway or route or a rein.

Room! room to be free, where the white-bordered sea

Blows a kiss to a brother as boundless as he;

Where the buffalo come like a cloud on the plain,

Pouring on like the tide of a storm-driven main,

And the lodge of the hunter to friend or to foe

Offers rest, and unquestioned you come or you go.

My plains of America! seas of wild lands!…

I turn to you, lean to you, lift you my hands.

Indeed, there was a splendid promise in Miller, but the promise was never fulfilled. He wrote voluminously, feeling that he must express the lure and magic of the boundless West; but he wrote so carelessly that the crude bulk of his verse obscures the originality of his few inspired lines. To read the latter is to be convinced that he was a true poet who might have accomplished a greater work than Whitman, since he had more genius and manliness than the eastern poet possessed; but his personal oddities, his zeal for reforms, his love of solitude, his endless quest after some unnamed good which kept him living among the Indians or wandering between Mexico and the ends of Alaska,–all this hindered his poetic development. It may be that an Indian-driven arrow, which touched his brain in one of his numerous adventures, had something to do with his wanderings and his failure.

There is a poetry of thought that can be written down in words, and there is another poetry of glorious living, keenly felt in the winds of the wilderness or the rush of a splendid horse or the flight of a canoe through the rapids, for which there is no adequate expression. Miller could feel superbly this poetry of the mountaineer, the plainsman and the voyageur; that he could even suggest or half reveal it to others makes him worthy to be named among our most original singers.

The hundred other poets of the period are too near for criticism, too varied even for classification; but we may at least note two or three significant groupings. In one group are the dialect poets, who attempt to make poetry serve the same end as fiction of the local-color school. Irwin Russell, with his gay negro songs tossed off to the twanging accompaniment of his banjo, belongs in this group. His verses are notable not for their dialect (others have done that better) but for their fidelity to the negro character as Russell had observed it in the old plantation days. There is little of poetic beauty in his work; it is chiefly remarkable for its promise, for its opening of a new field of poesie; but unfortunately the promise was spoiled by the author’s fitful life and his untimely death.

Closely akin to the dialect group in their effective use of the homely speech of country people are several popular poets, of whom Will Carleton and James Whitcomb Riley are the most conspicuous. Carleton’s “Over the Hills to the Poorhouse” and other early songs won him a wide circle of readers; whereupon he followed up his advantage with Farm Ballads and other volumes filled with rather crude but sincere verses of home and childhood. For half a century these sentimental poems were as popular as the early works of Longfellow, and they are still widely read by people who like homely themes and plenty of homely sentiment in their poetry.

Riley won an even larger following with his Old Swimmin’ Hole, Rhymes of Childhood Days and a dozen other volumes that aimed to reflect in rustic language the joys and sorrows of country people. Judged by the number of his readers he would be called the chief poet of the period; but judged by the quality of his work it would seem that he wrote too much, and wrote too often “with his eye on the gallery.” He was primarily an entertainer, a platform favorite, and in his impersonation of country folk was always in danger of giving his audience what he thought they would like, not what he sincerely felt to be true. Hence the impression of the stage and a “make-up” in a considerable part of his work. At times, however, Riley could forget the platform and speak from the heart as a plain man to plain men. His work at such moments has a deeper note, more simple and sincere, and a few of his poems will undoubtedly find a permanent place in American letters. The best feature of his work is that he felt no need to go far afield, to the Orient or to mythology, but found the beauty of fine feeling at his door and dared to call one of his collections Poems Here at Home.

In a third group of recent poets are those who try to reflect the feeling of some one type or race of the many that make up the sum total of American life. Such are Emma Lazarus, speaking finely for the Jewish race, and Paul Lawrence Dunbar, voicing the deeper life of the negro,–not the negro of the old plantation but the negro who was once a slave and must now prove himself a man. In the same group we are perhaps justified in placing Lucy Larcom, singing for the mill girls of New England, and Eugene Field, who shows what fun and sentiment may brighten the life of a busy newspaper man in a great city.

Finally come a larger number of poets who cannot be grouped, who sing each of what he knows or loves best: Celia Thaxter, of the storm-swept northern ocean; Madison Cawein, of nature in her more tender moods; Edward Rowland Sill, of the aspirations of a rare Puritan soul. More varied in their themes are Edith Thomas, Emily Dickinson, Henry C. Bunner, Richard Watson Gilder, George Edward Woodberry, William Vaughn Moody, Richard Hovey, and several others who are perhaps quite as notable as any of those whom we have too briefly reviewed. They all sing of American life in its wonderful complexity and have added poems of real merit to the book of recent American verse. And that is a very good book to read, more inspiring and perhaps more enduring than the popular book of prose fiction.

MISCELLANEOUS PROSE. The historian who is perplexed by our recent poetry or fiction must be overwhelmed by the flood of miscellaneous works covering every field of human endeavor. As one who wanders through a forest has no conception of the forest itself but only of individual trees, so the reader of latter-day literature can form no distinct impression of it as a whole but must linger over the individual authors who happen to attract his attention. Hence in all studies of contemporary literature we have the inevitable confusion of what is important with what merely seems so because of its nearness or newness or appeal to our personal interests. The reader is amused by a David Harum, or made thoughtful by a Looking Backward, or wonderstruck by a Life of Lincoln as big as a ten-volume history; and he thinks, “This is surely a book to live.” But a year passes and David Harum is eclipsed by a more popular hero of fiction, Looking Backward is relegated to the shelf of forgotten tracts, and Nicolay and Hay’s “monumental” biography becomes a source book, which someone, it is to be hoped, will some day use in making a life of Lincoln that will be worthy of the subject and of the name of literature.

There is one feature in our recent literature, however, which attracts the attention of all critics; namely, the number of nature writers who have revealed to us the beauty of our natural environment, as Ruskin awakened his readers to the beauty of art and Joaquin Miller to the unsung glory of the pioneers. In this respect, of adding to our enjoyment of human life by a new valuation of all life, our nature literature has no parallel in any age or nation.

To be specific, one must search continental literatures carefully to find even a single book that belongs unmistakably to the outdoor school. In English literature we find several poets who sing occasionally of the charms of nature, but only two books in fourteen centuries of writing that deal frankly with the great outdoors for its own sake: one is Isaac Walton’s Complete Angler (1653), the other Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne (1789). [Footnote: There were other works of a scientific nature, and some of exploration, but no real nature books until the first notable work of Richard Jefferies (one of the best of nature writers) appeared in 1878. By that time the nature movement in America was well under way.] In American literature the story is shorter but of the same tenor until recent times. From the beginning we have had many journals of exploration; but though the joy of wild nature is apparent in such writings, they were written to increase our knowledge, not our pleasure in life. Josselyn’s New England’s Rarities (1672), Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology (1801), Audubon’s Birds of America (1827),–these were our nearest approach to nature books until Thoreau’s Walden (1854) called attention to the immense and fascinating field which our writers had so long overlooked.

Thoreau, it will be remembered, was neglected by his own generation; but after the war, when writers began to use the picturesque characters of plantation or mining camp as the material for a new American literature, then the living world of nature seemed suddenly opened to their vision. Bradford Torrey, himself a charming nature writer, edited Thoreau’s journals, and lo! these neglected chronicles became precious because the eyes of America were at last opened. Maurice Thompson wrote as a poet and scholar in the presence of nature, John Muir as a reverent explorer, and William Hamilton Gibson as an artist with an eye single to beauty; then in rapid succession came Charles Abbott, Rowland Robinson, John Burroughs, Olive Thorne Miller, Florence Bailey, Frank Bolles, and a score more of a somewhat later generation. Most of these are frankly nature writers, not scientists; they aim not simply to observe the shy, fleeting life of the woods or fields but to reflect that life in such a way as to give us a new pleasure by awakening a new sense of beauty.

It is a remarkable spectacle, this rediscovery of nature in an age supposed to be given over to materialism, and its influence appears in every branch of our literature. The nature writers have evidently done a greater work than they knew; they have helped a multitude of people to enjoy the beauty of a flower without pulling it to pieces for a Latin name, to appreciate a living bird more than a stuffed skin, and to understand what Thoreau meant when he said that the anima of an animal is the only interesting thing about him. Because they have given us a new valuation of life, a new sense of its sacredness and mystery, their work may appeal to a future generation as the most original contribution to recent literature.

Another interesting feature of recent times is the importance attached to historical and biographical works, which have increased so rapidly since 1876 that there is now no period of American life and no important character or event that lacks its historian. The number of such works is astonishing, but their general lack of style and broad human interest places them outside of the field of literature. The tendency of recent historical writing, for example, is to collect facts about persons or events rather than to reproduce the persons or events so vividly that the past lives again before our eyes. The result of such writing is to make history a puppet show in which dead figures are moved about by unseen economic forces; meanwhile the only record that lives in literature is the one that represents history as it really was in the making; that is, as a drama of living, self-directing men.

There is at least one recent historian, however, whose style gives distinction to his work and makes it worthy of especial notice. This is John Fiske (1842-1901), whose field and method are both unusual. He began as a student of law and philosophy, and his first notable book, Outlines of Cosmic Philosophy, attracted instant attention in England and America by its literary style and rare lucidity of statement. It was followed by a series of essays, such as The Idea Of God, The Destiny Of Man and The Origin of Evil, which were so far above others of their kind that for a time they were in danger of becoming popular. Of a thousand works occasioned by the theory of evolution, when that theory was a nine days’ wonder, they are among the very few that stand the test of time by affording as much pleasure and surprise as when they were first written.

It was comparatively late in life that our philosopher turned historian, and his first work in this field, American Political Ideals Viewed from the Standpoint of Universal History, announced that here at last was a writer with broad horizons, who saw America not as an isolated nation making a strange experiment but as adding a vital chapter to the great world’s history. It was a surprising work, unlike any other in the field of American history, and it may fall to another generation to appreciate its originality. Finally Fiske took up the study of particular periods or epochs, viewed them with the same deep insight, the same broad sympathy, and reflected them in a series of brilliant narratives: Old Virginia and her Neighbors, The Beginnings of New England, Dutch and Quaker Colonies in America and a few others, the series ending chronologically with A Critical Period of American History, the “critical” period being the time of doubt and struggle over the Constitution. These narratives, though not unified, form a fairly complete history from the Colonial period to the formation of the Union.

To read any of these books is to discover that Fiske is concerned not chiefly with events but with the meaning or philosophy of events; that he has a rare gift of delving below the surface, of seeing in the endeavors of a handful of men at Jamestown or Plymouth or Philadelphia a profoundly significant chapter of universal history. Hence we seem to read in his pages not the story of America but the story of Man. Moreover, he had enthusiasm; which means that his heart was young and that he could make even dull matters vital and interesting. Perhaps the best thing that can be said of his work is that it is a pleasure to read it,–a criticism which is spoken for mature or thoughtful readers rather than for those who read history for its dramatic or heroic interest.

Another feature of our recent prose is the number of books devoted to the study of American letters; and that, like the study of nature, is a phenomenon which is without precedent. Notwithstanding Emerson’s plea for independence in The American Scholar (1837), our critics were busy long after that date with the books of other lands, thinking that there was no American literature worthy of their attention. In the same year that Emerson made his famous address Royal Robbins made what was probably the first attempt at a history of American literature. [Footnote: Chambers’ History of the English Language and Literature, to which is added A History of American Contributions to the English Language and Literature, by Royal Robbins (Hartford, 1837). It is interesting to note that the author complained of the difficulty of his task in view of the fact that there were at that time over two thousand living American authors.] It consisted of a few tag-ends attached to a dry catalogue of English writers, and the scholarly author declared that, as there was only one poor literary history then in existence (namely, Chambers’), he must depend largely on his own memory for correcting the English part of the book and creating a new American part. Nor were conditions improved during the next forty years.

After the war, however, the viewpoint of our historians was changed. They began to regard American literature with increasing respect as an original product, as a true reflection of human life in a new field and under the stimulus of new incentives to play the fine old game of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” In 1878 appeared Tyler’s History of American Literature 1607-1765 in two bulky volumes that surprised readers by revealing a mass of important writings in a period supposed to be barren of literary interest; and the surprise increased when the same author produced two more volumes dealing with the literature of the Revolution. In 1885 came Stedman’s Poets of America, an excellent critical study of New World poetry; and two years later Richardson published the first of his two splendid volumes of American Literature. These good beginnings were followed by a host of biographies dealing with every important American author, until we now have choice of a large assortment of literary material where Royal Robbins had none at all.

Such formal works are for the student, but the reader who goes to books for recreation has also been remembered. Edward Everett Hale’s James Russell Lowell and his Friends, Higginson’s Old Cambridge, Howells’s Literary Friends and Acquaintance, Trowbridge’s My Own Story, Mrs. Field’s Authors and Friends, Stoddard’s Homes and Haunts of our Elder Poets, Curtis’s Homes of American Authors, Mitchell’s American Lands and Letters,–these are but few of many recent books of reminiscences, all bearing witness to the fact that American literature has a history and tradition of its own. It is no longer an appendix to English literature but an original record, to be cherished as we cherish any other precious national heritage, and to stand or fall among the literatures of the world as it shall be found true or false to the fundamental ideals of American life.

* * * * *

BIBLIOGRAPHY. The best work on our recent literature is Pattee, A History of American Literature since 1870 (Century Co., 1915), which deals with two hundred or more writers. A more sketchy attempt at a contemporaneous history is Vedder, American Writers of Today (Silver, 1894, revised 1910), devoted to nineteen writers whom the author regards as most important.

From a multitude of books dealing with individual authors or with special types of literature we have selected the following brief list, which is suggestive rather than critical.

Study of Fiction. Henry James, The Art of Fiction; Howells, Criticism in Fiction; Crawford, The Novel: What It Is; Smith, The American Short Story; Canby, The Short Story in English.

Biography. Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe, by C. E. Stowe. Life of Bret Harte, by Pemberton, or by Merwin, or by Boynton. Life of Bayard Taylor, by Marie Taylor and Horace Scudder; or by Smyth, in American Men of Letters. Life of Stedman, by Laura Stedman and G. M. Gould. Life of Thomas Bailey Aldrich, by Greenslet. Letters of Sarah Orne Jewett, edited by Annie Fields. Life of Edward Rowland Sill, by Parker. Thompson’s Eugene Field. Mrs. Field’s Charles Dudley Warner. Grady’s Joel Chandler Harris. Life of Mark Twain, by Paine, 3 vols.

Historical and Reminiscent. Page, The Old South; Nicholson, The Hoosiers; Howells, My Literary Passions; Henry James, Notes of a Son and Brother; Stoddard, Recollections Personal and Literary, edited by Hitchcock; Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Chapters from a Life; Trowbridge, My Own Story.