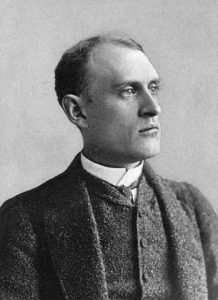

Eugene Field

A Memory

A Memory

When those we love have passed away; when from our lives something has gone out; when with each successive day we miss the presence that has become a part of ourselves, and struggle against the realization that it is with us no more, we begin to live in the past and thank God for the gracious boon of memory. Few of us there are who, having advanced to middle life, have not come to look back on the traveled road of human existence in thought of those who journeyed awhile with us, a part of all our hopes and joyousness, the sharers of all our ambitions and our pleasures, whose mission has been fulfilled and who have left us with the mile-stones of years still seeming to stretch out on the path ahead. It is then that memory comes with its soothing influence, telling us of the happiness that was ours and comforting us with the ever recurring thought of the pleasures of that traveled road. For it is happiness to walk and talk with a brother for forty years, and it is happiness to know that the surety of that brother’s affection, the knowledge of the greatness of his heart and the nobility of his mind, are not for one memory alone but may be publicly attested for admiration and emulation. That it has fallen to me to speak to the world of my brother as I knew him I rejoice. I do not fear that, speaking as a brother, I shall crowd the laurel wreaths upon him, for to this extent he lies in peace already honored; but if I can show him to the world, not as a poet but as a man,–if I may lead men to see more of that goodness, sweetness, and gentleness that were in him, I shall the more bless the memory that has survived.

My brother was born in St. Louis in 1850. Whether the exact day was September 2 or September 3 was a question over which he was given to speculation, more particularly in later years, when he was accustomed to discuss it frequently and with much earnest ness. In his youth the anniversary was generally held to be September 2, perhaps the result of a half-humorous remark by my father that Oliver Cromwell had died September 3, and he could not reconcile this date to the thought that it was an important anniversary to one of his children. Many years after, when my uncle, Charles Kellogg Field, of Vermont, published the genealogy of the Field family, the original date, September 3, was restored, and from that time my brother accepted it, although with each recurring anniversary the controversy was gravely renewed, much to the amusement of the family and always to his own perplexity.

In November, 1856, my mother died, and, at the breaking up of the family in St. Louis, my brother and myself, the last of six children, were taken to Amherst, Massachusetts, by our cousin, Miss Mary F. French, who took upon herself the care and responsibility of our bringing up. How nobly and self-sacrificingly she entered upon and discharged those duties my brother gladly testified in the beautiful dedication of his first published poems, “A Little Book of Western Verse,” wherein he honored the “gracious love” in which he grew, and bade her look as kindly on the faults of his pen as she had always looked on his own. For a few years my brother attended a private school for boys in Amherst; then, at the age of fourteen, he was entrusted to the care of Rev. James Tufts, of Monson, one of those noble instructors of the blessed old school who are passing away from the arena of education in America. By Mr. Tufts he was fitted for college, and from the enthusiasm of this old scholar he caught perhaps the inspiration for the love of the classics which he carried through life. In the fall of 1868 he entered Williams College—the choice was largely accidental—and remained there one year.

My father died in the summer of 1869, and my brother chose as his guardian Professor John William Burgess, now of Columbia University, New York City. When Professor Burgess, later in the summer, accepted a call to Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois, my brother accompanied him and entered that institution, but the restlessness which was so characteristic of him in youth asserted itself after another year and he joined me, then in my junior year at the University of Missouri, at Columbia. It was at this institution that he finished his education so far as it related to prescribed study.

Shortly after attaining his majority he went to Europe, remaining six months in France and Italy. From this European trip have sprung the absurd stories which have represented him as squandering thousands of dollars in the pursuit of pleasure. Unquestionably he had the not unnatural extravagance which accompanies youth and a most generous disposition, for he was lavish and open-handed all through life to an unusual degree, but at no time was he particularly given to wild excesses, and the fact that my father’s estate, which was largely realty, had shrunk perceptibly during the panic days of 1873 was enough to make him soon reach the limit of even moderate extravagance. At the same time many good stories have been told illustrative of his contempt for money, and it is eminently characteristic of his lack of the Puritan regard for small things that one day he approached my father’s executor, Hon. M. L. Gray, of St. Louis, with a request for seventy-five dollars.

“But,” objected this cautious and excellent man, “I gave you seventy-five dollars only yesterday, Eugene. What did you do with that?”

“Oh,” replied my brother, with an impatient and scornful toss of the head, “I believe I bought some postage stamps.”

Before going to Europe he had met Miss Julia Sutherland Comstock, of St. Joseph, Missouri, the sister of a college friend, and the attachment which was formed led to their marriage in October, 1873. Much of his tenderest and sweetest verse was inspired by love for the woman who became his wife, and the dedication to the “Second Book of Verse” is hardly surpassed for depth of affection and daintiness of sentiment, while “Lover’s Lane, St. Jo.,” is the very essence of loyalty, love, and reminiscential ardor. At the time of his marriage my brother realized the importance of going to work in earnest, and shortly before the appointment of the wedding-day he entered upon the active duties of journalism, which he never relinquished during life. These duties, with the exception of the year he passed in Europe with his family in 1889-90, were confined to the West. He began as a paragrapher in St. Louis, quickly achieving somewhat more than a merely local reputation.

For a time he was in St. Joseph, and for eighteen months following January 1880 he lived in Kansas City, removing thence to Denver. In 1883 he came to Chicago at the solicitation of Melville E. Stone, then editor of the Chicago Daily News, retaining his connection with the News and its offspring, the Record, until his death. Thus hastily have been skimmed over the bare outlines of his life.

The formative period of my brother’s youth was passed in New England, and to the influences which still prevail in and around her peaceful hills and gentle streams, the influences of a sturdy stock which has sent so many good and brave men to the West for the upbuilding of the country and the upholding of what is best in Puritan tradition, he gladly acknowledged he owed much that was strong and enduring. While he gloried in the West and remained loyal to the section which gave him birth, and in which he chose to cast his lot, he was not the less proud of his New England blood and not the less conscious of the benefits of a New England training. His boyhood was similar to that of other boys brought up with the best surroundings in a Massachusetts village, where the college atmosphere prevailed. He had his boyish pleasures and his trials, his share of that queer mixture of nineteenth-century worldliness and almost austere Puritanism which is yet characteristic of many New England families. The Sabbath was a veritable day of judgment, and in later years he spoke humorously of the terrors of those all-day sessions in church and Sunday-school, though he never failed to acknowledge the benefits he had derived from an enforced study of the Bible. “If I could be grateful to New England for nothing else,” he would say, “I should bless her forevermore for pounding me with the Bible and the spelling-book.” And in proof of the earnestness of this declaration he spent many hours in Boston a year or two ago, trying to find “one of those spellers that temporarily made me lose my faith in the system of the universe.”

It is easy at this day to look back three decades and note the characteristics which appeared trivial enough then, but which, clinging to him and developing, had a marked effect on his manhood and on the direction of his talents. As a boy his fondness for pets amounted to a passion, but unlike other boys he seemed to carry his pets into a higher sphere and to give them personality. For each pet, whether dog, cat, bird, goat, or squirrel—he had the family distrust of a horse—he not only had a name, but it was his delight to fancy that each possessed a peculiar dialect of human speech, and each he addressed in the humorous manner conceived. He ignored the names in common use for domestic animals and chose or invented those more pleasing to his exuberant fancy. This conceit was always with him, and years afterward, when his children took the place of his boyish pets, he gratified his whim for strange names by ignoring those designated at the baptismal font and substituting freakish titles of his own riotous fancy. Indeed it must have been a tax on his imaginative powers. When in childhood he was conducting a poultry annex to the homestead, each chicken was properly instructed to respond to a peculiar call, and Finnikin, Minnikin, Winnikin, Dump, Poog, Boog, seemed to recognize immediately the queer intonations of their master with an intelligence that is not usually accorded to chickens. With this love for animal life was developed also that tenderness of heart which was so manifest in my brother’s daily actions. One day—he was then a good-sized boy—he came into the house, and throwing himself on the sofa, sobbed for half an hour. One of the chickens hatched the day before had been crushed under his foot as he was walking in the chicken-house, and no murderer could have felt more keenly the pangs of remorse. The other boys looked on curiously at this exhibition of feeling, and it was indeed an unusual outburst. But it was strongly characteristic of him through life, and nothing would so excite his anger as cruelty to an animal, while every neglected, friendless dog or persecuted cat always found in him a champion and a friend.

In illustration of this humane instinct it is recalled that a few weeks before he died a lady visiting the house found his room swarming with flies. In response to her exclamation of astonishment he explained that a day or two before he had seen a poor, half-frozen fly on the window-pane outside, and he had been moved by a kindly impulse to open the window and admit her. “And this,” he added, “is what I get for it. That ungrateful creature is, as you perceive, the grandmother of eight thousand nine hundred and seventy-six flies!”

That the birds that flew about his house in Buena Park knew his voice has been demonstrated more than once. He would keep bread crumbs scattered along the window-sill for the benefit, as he explained, of the blue jays and the robins who were not in their usual robust health or were too overcome by the heat to make customary exertion. If the jays were particularly noisy he would go into the yard and expostulate with them in a tone of friendly reproach, whereupon, the family affirms, they would apparently apologize and fly away. Once he maintained at considerable expense a thoroughly hopeless and useless donkey, and it was his custom, when returning from the office at any hour of the night, to go into the back yard and say “Poor old Don” in a bass voice that carried a block away, whereupon old Don would lift up his own voice with a melancholy bray of welcome that would shake the windows and start the neighbors from their slumbers. Old Don is passing his declining years in an “Old Kentucky home,” and the robins and the blue jays as they return with the spring will look in vain for the friend who fed them at the window.

The family dog at Amherst, which was immortalized many years later with “The Bench-Legged Fyce,” and which was known in his day to hundreds of students at the college on account of his surpassing lack of beauty, rejoiced originally in the honest name of Fido, but my brother rejected this name as commonplace and unworthy, and straightway named him “Dooley” on the presumption that there was something Hibernian in his face. It was to Dooley that he wrote his first poem, a parody on “O Had I Wings Like a Dove,” a song then in great vogue. Near the head of the village street was the home of the Emersons, a large frame house, now standing for more than a century, and in the great yard in front stood the magnificent elms which are the glory of the Connecticut valley. Many times the boys, returning from school, would linger to cool off in the shade of these glorious trees, and it was on one of these occasions that my brother put into the mouth of Dooley his maiden effort in verse:

O had I wings like a dove I would fly,

Away from this world of fleas;

I’d fly all round Miss Emerson’s yard,

And light on Miss Emerson’s trees.

Even this startling parody, which was regarded by the boys as a veritable stroke of genius, failed to impress the adult villagers with the conviction that a poet was budding. Yet how much of quiet humor and lively imagination is betrayed by these four lines. How easy it is now to look back at the small boy and picture him sympathizing with his little friend tormented by the heat and the pests of his kind, and making him sigh for the rest that seemed to lurk in the rustling leaves of the stately elms. Perhaps it was not astonishing poetry even for a child, but was there not something in the fancy, the sentiment, and the rhythm which bespoke far more than ordinary appreciation? Is it not this same quality of alert and instinctive sympathy which has run through Eugene Field’s writings and touched the spring of popular affection?

Dooley went to the dog heaven many years ago. Finnikin and Poog and Boog and the scores of boyhood friends that followed them have passed to their Pythagorean reward; but the boy who first found in them the delight of companionship and the kindlings of imagination retained all the youthful impulses which made him for nearly half a century the lover of animal life and the gentle singer of the faithful and the good.

Comradeship was the indispensable factor in my brother’s life. It was strong in his youth; it grew to be an imperative necessity in later years. In the theory that it is sometimes good to be alone he had little or no faith. Even when he was at work in his study, when it was almost essential to thought that he should be undisturbed, he was never quite content unless aware of the presence of human beings near at hand, as betrayed by their voices. It is customary to think of a poet wandering off in the great solitudes, standing alone in contemplation of the wonderful work of nature, on the cliffs overlooking the ocean, in the paths of the forest or on the mountain side. My brother was not of this order. That he was primarily and essentially a poet of humanity and not of nature does not argue that he was insensible to natural beauty or natural grandeur. Nobody could have been more keenly susceptible to the influences of nature in their temperamental effect, and perhaps this may explain that he did not love nature the less but that he prized companionship more. If nature pleased him he longed for a friend to share his pleasure; if it appalled him he turned from it with repugnance and fear.

Throughout his writings may be found the most earnest appreciation of the joyousness and loveliness of a beautiful landscape, but as he would share it intellectually with his readers so it was a necessity that he could not seek it alone as an actuality. In his boyhood, in the full glory of a perfect day, he loved to ramble through the woods and meadows, and delighted in the azure tints of the far-away Berkshire hills; and later in life he was keen to notice and admire the soft harmonies of landscape, but with a change in weather or with the approach of a storm the poet would be lost in the timidity and distrust of a child.

Companionship with him meant cheerfulness. His horror of gloom and darkness was almost morbid. From the tragedies of life he instinctively shrank, and large as was his sympathy, and generous and genuine his affection, he was often prompted to run from suffering and to betray what must have been a constitutional terror of distress. He did not hesitate to acknowledge this characteristic, and sought to atone for it by writing the most tender and touching lines to those to whom he believed he owed a gift of comfort and strength. His private letters to friends in adversity or bereavement were beautiful in their simplicity and honest and outspoken love, for he was not ashamed to let his friends see how much he thought of them. And even if the emotional quality, which asserts itself in the nervous and artistic temperament, made him realize that he could not trust himself, that same quality gave him a personality marvelous in its magnetism. Both as boy and man he made friends everywhere, and that he retained them to the last speaks for the whole-heartedness and genuineness of his nature.

To two weaknesses he frankly confessed: that he was inclined to be superstitious and that he was afraid of the dark. One of these he stoutly defended, asserting that he who was not fearful in the dark was a dull clod, utterly devoid of imagination. From his earliest childhood my brother was a devourer of fairy tales, and he continually stored his mind with fantastic legends, which found a vent in new shapes in his verses and prose tales. In the ceiling of one of his dens a trap-door led into the attic, and as this door was open he seriously contemplated closing it, because, as he said, he fancied that queer things would come down in the night and spirit him away. It is not to be inferred that he thus remained in a condition of actual fear, but it is true that he was imaginative to the degree of acute nervousness, and, like a child, associated light with safety and darkness with the uncanny and the supernatural. It was after all the better for his songs that it was so, else they might not have been filled with that cheery optimism which praised the happiness of sunlight and warmth, and sought to lift humanity from the darkness of despondency.

This weakness, or intellectual virtue as he pleasantly regarded it, was perhaps rather stronger in him as a man than in his boyhood. He has himself declared that he wrote “Seein’ Things at Night” more to solace his own feelings than to delineate the sufferings of childhood, however aptly it may describe them. And when he put into rhythm that “any color, so long as it’s red, is the color that suits me best,” he spoke not only as a poet but as a man, for red conveyed to him the idea of warmth and cheeriness, and seemed to express to him in color his temperamental demand. All through his life he pandered to these feelings instead of seeking to repress them, for to this extent there was little of the Puritan in his nature, and as he believed that happiness comes largely from within, so he felt that it is not un-Christian philosophy to avoid as far as possible whatever may cloud and render less acceptable one’s own existence.

The literary talent of my brother is not easily traceable to either branch of the family. In fact it was tacitly accepted that he would be a lawyer as his father and grandfather had been before him, but the futility of this arrangement was soon manifest, and surely no man less temperamentally equipped for the law ever lived. It has been said of the Fields, speaking generally of the New England division, that they were well adapted to be either musicians or actors, though the talent for music or mimicry has been in no case carried out of private life save in my brother’s public readings. Eugene had more than a boy’s share of musical talent, but he never cultivated it, preferring to use the fine voice with which he was endowed for recitation, of which he was always fond. Acting was his strongest boyish passion. Even as a child he was a wonderful mimic and thereby the delight of his playmates and the terror of his teachers. He organized a stock company among the small boys of the village and gave performances in the barn of one of the less scrupulous neighbors, but whether for pins or pennies memory does not suggest. He assigned the parts and always reserved for himself the eccentric character and the low comedy, caring nothing for the heroic or the sentimental. One of the plays performed was Lester Wallack’s “Rosedale” with Eugene in the dual role of the low comedian and the heavy villain. At this time also he delighted in monologues, imitations of eccentric types, or what Mr. Sol. Smith Russell calls “comics,” a word which always amused Eugene and which he frequently used. This fondness for parlor readings and private theatricals he carried through college, remaining steadfast to the “comics” until a few years ago, when he began to give public readings, and discovered that he was capable of higher and more effective work. It was in fact his versatility that made him the most accomplished and the most popular author-entertainer in America. Before he went into journalism the more sedate of his family connections were in constant fear lest he should adopt the profession of the actor, and he held it over them as a good-natured threat. On one occasion, failing to get a coveted appropriation from the executor of the estate, he said calmly to the worthy man: “Very well. I must have money for my living expenses. If you cannot advance it to me out of the estate I shall be compelled to go on the stage. But as I cannot keep my own name I have decided to assume yours, and shall have lithographs struck off at once. They will read, ‘Tonight, M. L. Gray, Banjo and Specialty Artist.’” The appropriation was immediately forthcoming.

It is in no sense depreciatory of my brother’s attainments in life to say that he gave no evidence of precocity in his studies in childhood. On the contrary he was somewhat slow in development, though this was due not so much to a lack of natural ability— e learned easily and quickly when so disposed—as to a fondness for the hundred diversions which occupy a wide-awake boy’s time. He possessed a marked talent for caricature, and not a small part of the study hours was devoted to amusing pictures of his teachers, his playmates, and his pets. This habit of drawing, which was wholly without instruction, he always preserved, and it was his honest opinion, even at the height of his success in authorship, that he would have been much greater as a caricaturist than as a writer. Until he was thirty years of age he wrote a fair-sized legible hand, but about that time he adopted the microscopic penmanship which has been so widely reproduced, using for the purpose very fine-pointed pens. With his manuscript he took the greatest pains, often going to infinite trouble to illuminate his letters. Among his friends these letters are held as curiosities of literature, hardly more for the quaint sentiments expressed than for the queer designs in colored inks which embellished them. He was specially fond of drawing weird elves and gnomes, and would spend an hour or two decorating with these comical figures a letter he had written in ten minutes. He was as fastidious with the manuscript for the office as if it had been a specimen copy for exhibition, and it was always understood that his manuscript should be returned to him after it had passed through the printers’ hands. In this way all the original copies of his stories and poems have been preserved, and those which he did not give to friends as souvenirs have been bound for his children.

A taste for literary composition might not have passed, as doubtless it did pass, so many years unnoticed, had he been deficient in other talents, and had he devoted himself exclusively to writing. But as a boy he was fond, though in a less degree than many boys, of athletic sports, and his youthful desire for theatrical entertainments, pen caricaturing, and dallying with his pets took up much of his time. Yet he often gave way to a fondness for composition, and there is in the family possession a sermon which he wrote before he was ten years of age, in which he showed the results of those arduous Sabbath days in the old Congregational meeting-house. And at one time, when yet very young, he was at the head of a flourishing boys’ paper, while at another, fresh from the inspiration of a blood-curdling romance in a New York Weekly, he prepared a series of tales of adventure which, unhappily, have not been preserved. In his college days he was one of the associate editors of the university magazine, and while at that time he had no serious thought of devoting his life to literature, his talents in that direction were freely confessed. From my father, whose studious habits in life had made him not only eminent at the bar but profoundly conversant with general literature, he had inherited a taste for reading, and it was this omnivorous passion for books that led my brother to say that his education had only begun when he fancied that it had left off. In boyhood he contracted that fascinating but highly injurious habit of reading in bed, which he subsequently extolled with great fervor; and as he grew older the habit increased upon him until he was obliged to admit that he could not enjoy literature unless he took it horizontally. If a friend expostulated with him, advising him to give up tobacco, reading in bed, and late hours, he said: “And what have we left in life if we give up all our bad habits?”

That the poetic instinct was always strong within him there has never been room to question, but, perhaps, for the reasons before assigned, it was tardy in making its way outward. For years his mind lay fallow and receptive, awaiting the occasion which should develop the true inspiration of the poet. He was accustomed to speak of himself, and too modestly, as merely a versifier, but his own experience should have contradicted this estimate, for his first efforts at verse were singularly halting in mechanical construction, and he was well past his twenty-fifth year before he gave to the world any verse worthy the name. What might be called the “curse of comedy” was on him, and it was not until he threw off that yoke and gave expression to the better and the sweeter thoughts within him that, as with Bion, “the voice of song flowed freely from the heart.” It seems strange that a man who became a master of the art of mechanism in verse should have been deficient in this particular at a period comparatively late, but it merely illustrates the theory of gradual development and marks the phases of life through which, with his character of many sides, he was compelled to pass. He was nearly thirty when he wrote “Christmas Treasures,” the first poem he deemed worthy, and very properly, of preservation, and the publication of this tender commemoration of the death of a child opened the springs of sentiment and love for childhood destined never to run dry while life endured.

In journalism he became immediately successful, not so much for adaptability to the treadmill of that calling as for the brightness and distinctive character of his writing. He easily established a reputation as a humorist, and while he fairly deserved the title he often regretted that he could not entirely shake it off. His powers of perception were phenomenally keen, and he detected the peculiarities of people with whom he was thrown in contact almost at a glance, while his gift of mimicry was such that after a minute’s interview he could burlesque the victim to the life, even emphasizing the small details which had been apparently too minute to attract the special notice of those who were acquaintances of years’ standing. This faculty he carried into his writing, and it proved immensely valuable, for, with his quick appreciation of the ludicrous and his power of delineating personal peculiarities his sketches were remarkable for their resemblances even when he was indulging apparently in the wildest flights of imagination.

It is to be regretted that much of his newspaper work, covering a period of twenty years, was necessarily so full of purely local color that its brilliancy could not be generally appreciated. For it is as if an artist had painted a wondrous picture, clever enough in the general view, but full of a significance hidden to the world.

Equally facile was he in the way of adaptation. He could write a hoax worthy of Poe, and one of his humors of imagination was sufficiently subtle and successful to excite comment in Europe and America, and to call for an explanation and denial from a distinguished Englishman. He lived in Denver only a few weeks when he was writing verse in miners’ dialect which has been rightly placed at the head of that style of composition. No matter where he wandered, he speedily became imbued with the spirit of his surroundings, and his quickly and accurately gathered impressions found vent in his pen, whether he was in “St. Martin’s Lane” in London, with “Mynheer Von Der Bloom” in Amsterdam, or on the “Schnellest Zug” from Hanover to Leipzig.

At the time of my brother’s arrival in Chicago, in 1883–he was then in his thirty-fourth year—he had performed an immense amount of newspaper work, but had done little or nothing of permanent value or with any real literary significance. But despite the fact that he had lived up to that time in the smaller cities he had a large number of acquaintances and a certain following in the journalistic and artistic world, of which from the very moment of his entrance into journalism he never had been deprived. His immense fund of good humor, his powers as a story-teller, his admirable equipment as an entertainer, and the wholehearted way with which he threw himself into life and the pleasures of living attracted men to him and kept him the centre of the multitude that prized his fascinating companionship. His fellows in journalism furthermore had been quick to recognize his talents, and no man was more widely “copied,” as the technical expression goes. His early years in Chicago did not differ materially from those of the previous decade, but the enlarged scope gave greater play to his fancy and more opportunity for his talents as a master of satire. The publication of “The Denver Primer” and “Culture’s Garland,” while adding to his reputation as a humorist, happily did not satisfy him. He was now past the age of thirty-five, and a great psychical revolution was coming on. Though still on the sunny side of middle life, he was wearying of the cup of pleasure he had drunk so joyously, and was drawing away from the multitude and toward the companionship of those who loved books and bookish things, and who could sympathize with him in the aspirations for the better work, the consciousness of which had dawned. It was now that he began to apply himself diligently to the preparation for higher effort, and it is to the credit of journalism, which has so many sins to answer for, that in this he was encouraged beyond the usual fate of men who become slaves to that calling. And yet, though from this time he was privileged to be regarded one of the sweetest singers in American literature, and incomparably the noblest bard of childhood, though the grind of journalism was measurably taken from him, he chafed under the conviction that he was condemned to mingle the prosaic and the practical with the fanciful and the ideal, and that, having given hostages to fortune, he must conform even in a measure to the requirements of a position too lucrative to be cast aside. From this time also his physical condition, which never had been robust, began to show the effects of sedentary life, but the warning of a long siege of nervous dyspepsia was suffered to pass unheeded, and for five or six years he labored prodigiously, his mind expanding and his intellect growing more brilliant as the vital powers decayed.

It would seem that with the awakening of the consciousness of the better powers within him, with the realization that he was destined for a place in literature, my brother felt a quasi remorse for the years he fancied he had wasted. He was too severe with himself to understand that his comparative tardiness in arriving at the earnest, thoughtful stage of lifework was the inexorable law of gradual development which must govern the career of a man of his temperament, with his exuberant vitality and his showy talents. It was a serious mistake, but it was not the less a noble one. And now also the influences of home crept a little closer into his heart. His family life had not been without its tragedies of bereavement, and the death of his oldest boy in Germany had drawn him even nearer to the children who were growing up around him.

Much of his tenderest verse was inspired by affection for his family, and as some great shock is often essential to the revolution in a buoyant nature, so it seemed to require the oft-recurring tragedies of life to draw from him all that was noblest and sweetest in his sympathetic soul. Had the angel of death never hovered over the crib in my brother’s home, had he never known the pangs and the heart-hunger which come when the little voice is stilled and the little chair is empty, he could not have written the lines which voice the great cry of humanity and the hope of reunion in immortality beyond the grave.

The flood of appeals for platform readings from cities and towns in all parts of the United States came too late for his physical strength and his ambition. Earlier in life he would have delighted in this form of travel and entertainment, but his nature had wonderfully changed, and, strong as were the financial inducements, he was loath to leave his family and circle of intimate friends, and the home he had just acquired. All of the time which he allotted for recreation he devoted to working around his grounds, in arranging and rearranging his large library, and in the disposition of his curios. For years he had been an indefatigable collector, and he took a boyish pleasure not only in his souvenirs of long journeys and distinguished men and women, but in the queer toys and trinkets of children which seemed to give him inspiration for much that was effective in childhood verse. To the careless observer the immense array of weird dolls and absurd toys in his working-room meant little more than an idiosyncratic passion for the anomalous, but those who were near to him knew what a connecting link they were between him and the little children of whom he wrote, and how each trumpet and drum, each “spinster doll,” each little toy dog, each little tin soldier, played its part in the poems he sent out into the world. No writer ever made more persistent and consistent use of the material by which he was surrounded, or put a higher literary value on the little things which go to make up the sum of human existence.

Of the spiritual development of my brother much might be said in conviction and in tenderness. He was not a man who discussed religion freely; he was associated with no religious denomination, and he professed no creed beyond the brotherhood of mankind and the infinitude of God’s love and mercy. In childhood he had been reared in much of the austerity of the Puritan doctrine of the relation of this life to the hereafter, and much of the hardness and severity of Christianity, as still interpreted in many parts of New England, was forced upon him. As is not unusual in such cases, he rebelled against this conception of God and God’s day, even while he confessed the intellectual advantages he had reaped from frequent compulsory communion with the Bible, and he many times declared that his children should not be brought up to regard religion and the Sabbath as a bugbear. What evolution was going on in his mind at the turning point in his life who can say? Who shall look into the silent soul of the poet and see the hope and confidence and joy that have come from out the chaos of strife and doubt? Yet who can read the verses, telling over and over the beautiful story of Bethlehem, the glory of the Christ-child and the comfort that comes from the Teacher, and doubt that in those moments he walked in the light of the love of God?

It is true that no man living in a Christian nation who is stirred by poetic instinct can fail to recognize and pay homage to that story of wonderful sweetness, the coming of the Christ-child for the redemption of the world. It is true that in commemoration the poet may speak while the man within is silent. But it is hardly true that he whose generous soul responded to every principle of Christ, the Teacher, pleading for humanity, would sing over and over that tender song of love and sacrifice as a mere poetic inspiration. As he slept my brother’s soul was called. Who shall say that it was not summoned by that same angel song that awakened “Little Boy Blue”? Who shall doubt that the smile of supreme peace and rest which lingered on his face after that noble spirit had departed spoke for the victory he had won, for the hope and belief that had been justified, and for the happiness he had gained?

To have been with my brother in the last year of his life, to have seen the sweetening of a character already lovable to an unusual degree, to know now that in his unconscious preparation for the life beyond he was drawing closer to those he loved and who loved him, this is the tenderest memory, the most precious heritage. Not to have seen him in that year is never to realize the full beauty of his nature, the complete development of his nobler self, the perfect abandonment of all that might have been ungenerous and intemperate in one even less conscious of the weakness of mortality. He would say when chided for public expression of kind words to those not wholly deserving, that he had felt the sting of harshness and ungraciousness, and never again would he use his power to inflict suffering or wound the feelings of man or child. Who is there to wonder, then, that the love of all went out to him, and that the other triumphs of his life were as nothing in comparison with the grasp he maintained on popular affection? The day after his death a lady was purchasing flowers to send in sympathy for the mourning family, when she was approached by a poorly-clad little girl who timidly asked what she was going to do with so many roses. When she replied that she intended sending them to Mr. Field, the little one said that she wanted so much to send Mr. Field a rose, adding pathetically that she had no money. Deeply touched by the child’s sorrowful earnestness the lady picked out a yellow rose and gave it to her, and when the coffin was lowered to the grave a wealth of wreaths and designs was strewn around to mark the spot, but down below the hand of the silent poet held only a little yellow rose, the tribute of a child who did not know him in life, but in whose heart nestled the love his songs had awakened and the magnetism of his great humanity had stirred.

A few hours after his spirit had gone a crippled boy came to the house and begged permission to go to the chamber. The wish was granted, and the boy hobbled to the bedside. Who he was, and in what manner my brother had befriended him, none of the family knew, but as he painfully picked his way down stairs the tears were streaming over his face, and the onlookers forgot their own sorrow in contemplation of his grief.

The morning of the funeral, while the family stood around the coffin, the letter-carrier at Buena Park came into the room, and laying a bunch of letters at the foot of the bier said reverently: “There is your last mail, Mr. Field.” Then turning with tears in his eyes, as if apologizing for an intrusion, he added: “He was always good to me and I loved him.”

It was this affection of those in humbler life that seems to speak the more eloquently for the beneficence and the triumph of his life’s work.

No funeral could have been less ostentatious, yet none could have been more impressive in the multitude that overflowed the church, or more conformable to his tenacious belief in the democracy of man. People of eminence, of wealth, of fashion, were there, but they were swallowed up in the great congregation of those to whom we are bound by the ties of humanity and universal brotherhood, whose tears as they passed the bier of the dead singer were the earnest and the best tribute to him who sang for all. What greater blessing hath man than this? What stronger assurance can there be of happiness in that life where all is weighed in the scale of love, and where love is triumphant and eternal?

Sleep, my brother, in the perfect joy of an awakening to that happiness beyond the probationary life. Sleep in the assurance that those who loved you will always cherish the memory of that love as the tender inspiration of your gentle spirit. Sleep and dream that the songs you sang will still be sung when those who sing them now are sleeping with you. Sleep and take your rest as calmly and peacefully as you slept when your last “Good-Night” lengthened into eternity. And if the Horace you so merrily invoked comes to you in your slumber and bids you awake to that sweet cheer, that “fellowship that knows no end beyond the misty Stygian sea,” tell him that the time has not yet come, and that there are those yet uncalled, to whom you have pledged the joyous meeting on yonder shore, and who would share with you the heaven your companionship would brighten.

ROSWELL MARTIN FIELD.

BUENA PARK, January, 1896.