Palenque

(This is taken from John D. Baldwin’s Ancient America, originally published in 1871.)

(This is taken from John D. Baldwin’s Ancient America, originally published in 1871.)

To understand the situation and historical significance of the more important antiquities in Southern Mexico and Central America, we must keep in view their situation relative to the great unexplored forest to which attention has been called. Examine carefully any good map of Mexico and Central America, and consider well that the ruins already explored or visited are wholly in the northern half of Yucatan, or far away from this region, at the south, beyond the great wilderness, or in the southern edge of it. Uxmal, Mayapan, Chichen-Itza, and many others, are in Yucatan. Palenque, Copan, and others are in the southern part of the wilderness, in Chiapa, Honduras, and Guatemala. Mr. Squier visited ruins much farther south, in San Salvador, and in the western parts of Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

The vast forest which is spread over the northern half of Guatemala and the southern half of Yucatan, and extended into other states, covers an area considerably larger in extent than Ohio or Pennsylvania. Does its position relative to the known ruins afford no suggestion concerning the ancient history of this forest-covered region? It is manifest that, in the remote ages when the older of the cities now in ruins were built, this region was a populous and important part of the country. And this is shown also by the antiquities found wherever it has been penetrated by explorers who knew how to make discoveries, as well as by the old books and traditions. Therefore it is not unreasonable to assume that Copan and Palenque are specimens of great ruins that lie buried in it. The ruins of which something is known have merely been visited and described in part by explorers, some of whom brought away drawings of the principal objects. In giving a brief account of the more important ruins, I will begin with the old city of which most has been heard.

PALENQUE.

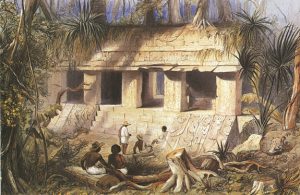

No one can tell the true name of the ancient city now called Palenque. It is known to us by this name because the ruins are situated a few miles distant from the town of Palenque, now a village, but formerly a place of some importance. The ruins are in the northern part of the Mexican State of Chiapa, hidden out of sight in the forest, where they seem to have been forgotten long before the time of Cortez. More than two hundred years passed after the arrival of the Spaniards before their existence became known to Europeans. They were discovered about the year 1750. Since that year decay has made some progress in them. Captain Del Rio, who visited and described them in 1787, examined “fourteen edifices” admirably built of hewn stone, and estimated the extent of the ruins to be “seven or eight leagues one way [along the River Chacamas], and half a league the other.” He mentions “a subterranean aqueduct of great solidity and durability, which passes under the largest building.”

Other explorers have since visited Palenque, and reported on the ruins by pen and pencil; but it is not certain that all the ruined edifices belonging to them have been seen, nor that the explorations have made it possible to determine the ancient extent of the city with any approach to accuracy. The very great difficulties which obstruct all attempts at complete exploration have not allowed any explorer to say he has examined or discovered all the mouldering monuments hidden in the dense and tangled forest, even within the space allowed by Del Rio’s “half league” from the river, not to speak of what may lie buried and unknown in the dense mass of trees and undergrowth beyond this limit.

The largest known building at Palenque is called the “Palace.” It stands near the river, on a terraced pyramidal foundation 40 feet high and 310 feet long, by 260 broad at the base. The edifice itself is 228 feet long, 180 wide, and 25 feet high. It faces the east, and has 14 doorways on each side, with 11 at the ends. It was built entirely of hewn stone, laid with admirable precision in mortar which seems to have been of the best quality. A corridor 9 feet wide, and roofed by a pointed arch, went round the building on the outside; and this was separated from another within of equal width. The “Palace” has four interior courts, the largest being 70 by 80 feet in extent. These are surrounded by corridors, and the architectural work facing them is richly decorated. Within the building were many rooms. From the north side of one of the smaller courts rises a high tower, or pagoda-like structure, thirty feet square at the base, which goes up far above the highest elevation of the building, and seems to have been still higher when the whole structure was in perfect condition. The great rectangular mound used for the foundation was cased with hewn stone, the workmanship here, and every where else throughout the structure, being very superior. The piers around the courts are “covered with figures in stucco, or plaster, which, where broken, reveals six or more coats or layers, each revealing traces of painting.” This indicates that the building had been used so long before it was deserted that the plastering needed to be many times renewed. There is some evidence that painting was used as a means of decoration; but that which most engages attention is the artistic management of the stone-work, and, above all, the beautifully executed sculptures for ornamentation.

The cross, even the so-called Latin cross, is not exclusively a Christian emblem. It was used in the Oriental world many centuries (perhaps millenniums) before the Christian era. It was a religious emblem of the Phœnicians, associated with Astarte, who is usually figured bearing what is called a Latin cross. She is seen so figured on Phœnician coin. The cross is found in the ruins of Nineveh. Mr. Layard, describing one of the finest specimens of Assyrian sculpture (the figure of “an early Nimrod king” he calls it), says: “Round his neck are hung the four sacred signs; the crescent, the star or sun, the trident, and the cross.” These “signs,” the cross included, appear suspended from the necks or collars of Oriental prisoners figured on Egyptian monuments known to be fifteen hundred years older than the Christian era. The cross was a common emblem in ancient Egypt, and the Latin form of it was used in the religious mysteries of that country, in connection with a monogram of the moon. It was to degrade this religious emblem of the Phœnicians that Alexander ordered the execution of two thousand principal citizens of Tyre by crucifixion.

The cross, as an emblem, is very common among the antiquities of Western Europe, where archæological investigation has sometimes been embarrassed and confused by the assumption that any old monument bearing the figure of a cross can not be as old as Christianity.

What more will be found at Palenque, when the whole field of its ruins has been explored, can not now be reported. The chief difficulty by which explorers are embarrassed is manifest in this statement of Mr. Stephens: “Without a guide, we might have gone within a hundred feet of the buildings without discovering one of them.” More has been discovered there than I have mentioned, my purpose being to give an accurate view of the style, finish, decoration, and general character of the architecture and artistic work found in the ruins rather than a complete account of every thing connected with them. The ruins of Palenque are deemed important by archæologists partly on account of the great abundance of inscriptions found there, which, it is believed, will at length be deciphered, the written characters being similar to those of the Mayas, which are now understood.