The Age of Chaucer and the Revival of Learning

[This is taken from William J. Long’s Outlines of English and American Literature.]

[This is taken from William J. Long’s Outlines of English and American Literature.]

For out of oldë feldës, as men seith,

Cometh al this newë corn fro yeer te yere;

And out of oldë bokës, in good feith,

Cometh all this newë science that men lere.

Chaucer, “Parliament of Foules”

SPECIMENS OF THE LANGUAGE. Our first selection, from Piers Plowman (cir. 1362), is the satire of Belling the Cat. The language is that of the common people, and the verse is in the old Saxon manner, with accent and alliteration. The scene is a council of rats and mice (common people) called to consider how best to deal with the cat (court), and it satirizes the popular agitators who declaim against the government. The speaker is a rat, “a raton of renon, most renable of tonge”:

“I have y-seen segges,” quod he,

“in the cite of London

Beren beighes ful brighte

abouten here nekkes….Were there a belle on here beighe,

certes, as me thynketh,

Men myghte wite where thei went,

and awei renne!And right so,” quod this raton,

“reson me sheweth

To bugge a belle of brasse

or of brighte sylver,

And knitten on a colere

for owre comune profit,

And hangen it upon the cattes hals;

than hear we mowen

Where he ritt or rest

or renneth to playe.” …Alle this route of ratones

to this reson thei assented;

Ac tho the belle was y-bought

and on the beighe hanged,

Ther ne was ratoun in alle the route,

for alle the rewme of Fraunce,

That dorst have y-bounden the belle

aboute the cattis nekke.“I have seen creatures” (dogs), quoth he,

“in the city of London

Bearing collars full bright

around their necks….Were there a bell on those collars,

assuredly, in my opinion,

One might know where the dogs go,

and run away from them!And right so,” quoth this rat,

“reason suggests to me

To buy a bell of brass

or of bright silver,

And tie it on a collar

for our common profit,

And hang it on the cat’s neck;

in order that we may hear

Where he rides or rests

or runneth to play.” …All this rout (crowd) of rats

to this reasoning assented;

But when the bell was bought

and hanged on the collar,

There was not a rat in the crowd

that, for all the realm of France

Would have dared to bind the bell

about the cat’s neck.

The second selection is from Chaucer’s “Wife of Bath’s Tale” (cir. 1375). It was written “in the French manner” with rime and meter, for the upper classes, and shows the difference between literary English and the speech of the common people:

In th’ olde dayës of the Kyng Arthour,

Of which that Britons speken greet honour,

Al was this land fulfild of fayerye.

The elf-queene with hir joly companye

Dauncëd ful ofte in many a grene mede;

This was the olde opinion, as I rede.

I speke of manye hundred yeres ago;

But now kan no man see none elves mo.

The next two selections (written cir. 1450) show how rapidly the language was approaching modern English. The prose, from Malory’s Morte d’ Arthur, is the selection that Tennyson closely followed in his “Passing of Arthur.” The poetry, from the ballad of “Robin Hood and the Monk,” is probably a fifteenth-century version of a much older English song:

“’Therefore,’ sayd Arthur unto Syr Bedwere, ‘take thou Excalybur my good swerde, and goo with it, to yonder water syde, and whan thou comest there I charge the throwe my swerde in that water, and come ageyn and telle me what thou there seest.’

“’My lord,’ sayd Bedwere, ‘your commaundement shal be doon, and lyghtly brynge you worde ageyn.’

“So Syr Bedwere departed; and by the waye he behelde that noble swerde, that the pomel and the hafte was al of precyous stones; and thenne he sayd to hym self, ‘Yf I throwe this ryche swerde in the water, thereof shal never come good, but harme and losse.’ And thenne Syr Bedwere hydde Excalybur under a tree.”

In somer, when the shawes be sheyne,

And leves be large and long,

Hit is full mery in feyr foreste

To here the foulys song:

To se the dere draw to the dale,

And leve the hillës hee,

And shadow hem in the levës grene,

Under the grene-wode tre.

HISTORICAL OUTLINE. The history of England during this period is largely a record of strife and confusion. The struggle of the House of Commons against the despotism of kings; the Hundred Years War with France, in which those whose fathers had been Celts, Danes, Saxons, Normans, were now fighting shoulder to shoulder as Englishmen all; the suffering of the common people, resulting in the Peasant Rebellion; the barbarity of the nobles, who were destroying one another in the Wars of the Roses; the beginning of commerce and manufacturing, following the lead of Holland, and the rise of a powerful middle class; the belated appearance of the Renaissance, welcomed by a few scholars but unnoticed by the masses of people, who remained in dense ignorance,–even such a brief catalogue suggests that many books must be read before we can enter into the spirit of fourteenth-century England. We shall note here only two circumstances, which may help us to understand Chaucer and the age in which he lived.

The first is that the age of Chaucer, if examined carefully, shows many striking resemblances to our own. It was, for example, an age of warfare; and, as in our own age of hideous inventions, military methods were all upset by the discovery that the foot soldier with his blunderbuss was more potent than the panoplied knight on horseback. While war raged abroad, there was no end of labor troubles at home, strikes, “lockouts,” assaults on imported workmen (the Flemish weavers brought in by Edward III), and no end of experimental laws to remedy the evil. The Turk came into Europe, introducing the Eastern and the Balkan questions, which have ever since troubled us. Imperialism was rampant, in Edward’s claim to France, for example, or in John of Gaunt’s attempt to annex Castile. Even “feminism” was in the air, and its merits were shrewdly debated by Chaucer’s Wife of Bath and his Clerk of Oxenford. A dozen other “modern” examples might be given, but the sum of the matter is this: that there is hardly a social or political or economic problem of the past fifty years that was not violently agitated in the latter half of the fourteenth century.

A second interesting circumstance is that this medieval age produced two poets, Langland and Chaucer, who were more realistic even than present-day writers in their portrayal of life, and who together gave us such a picture of English society as no other poets have ever equaled. Langland wrote his Piers Plowman in the familiar Anglo-Saxon style for the common people, and pictured their life to the letter; while Chaucer wrote his Canterbury Tales, a poem shaped after Italian and French models, portraying the holiday side of the middle and upper classes. Langland drew a terrible picture of a degraded land, desperately in need of justice, of education, of reform in church and state;

Chaucer showed a gay company of pilgrims riding through a prosperous country which he called his “Merrie England.” Perhaps the one thing in common with these two poets, the early types of Puritan and Cavalier, was their attitude towards democracy. Langland preached the gospel of labor, far more powerfully than Carlyle ever preached it, and exalted honest work as the patent of nobility. Chaucer, writing for the court, mingled his characters in the most democratic kind of fellowship and, though a knight rode at the head of his procession, put into the mouth of the Wife of Bath his definition of a gentleman:

Loke who that is most vertuous alway,

Privee and apert, and most entendeth aye

To do the gentle dedes that he can,

And take him for the grettest gentilman.

* * * * *

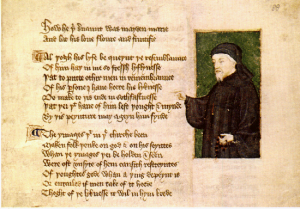

GEOFFREY CHAUCER (cir. 1340-1400)

“Of Chaucer truly I know not whether to marvel more, either that he in that misty time could see so clearly, or that we in this clear age walk so stumblingly after him.”

(Philip Sidney, cir. 1581)

It was the habit of Old-English chieftains to take their scops with them into battle, to the end that the scop’s poem might be true to the outer world of fact as well as to the inner world of ideals. The search for “local color” is, therefore, not the newest thing in fiction but the oldest thing in poetry. Chaucer, the first in time of our great English poets, was true to this old tradition. He was page, squire, soldier, statesman, diplomat, traveler; and then he was a poet, who portrayed in verse the many-colored life which he knew intimately at first hand.

For example, Chaucer had to describe a tournament, in the Knight’s Tale; but instead of using his imagination, as other romancers had always done, he drew a vivid picture of one of those gorgeous pageants of decaying chivalry with which London diverted the French king, who had been brought prisoner to the city after the victory of the Black Prince at Poitiers. So with his Tabard Inn, which is a real English inn, and with his Pilgrims, who are real pilgrims; and so with every other scene or character he described. His specialty was human nature, his strong point observation, his method essentially modern. And by “modern” we mean that he portrayed the men and women of his own day so well, with such sympathy and humor and wisdom, that we recognize and welcome them as friends or neighbors, who are the same in all ages. From this viewpoint Chaucer is more modern than Tennyson or Longfellow.

LIFE. Chaucer’s boyhood was spent in London, near Westminster, where the brilliant court of Edward was visible to the favored ones; and near the Thames, where the world’s commerce, then beginning to ebb and flow with the tides, might be seen of every man. His father was a vintner, or wine merchant, who had enough influence at court to obtain for his son a place in the house of the Princess Elizabeth. Behold then our future poet beginning his knightly training as page to a highborn lady. Presently he accompanied the Black Prince to the French wars, was taken prisoner and ransomed, and on his return entered the second stage of knighthood as esquire or personal attendant to the king. He married a maid of honor related to John of Gaunt, the famous Duke of Lancaster, and at thirty had passed from the rank of merchant into official and aristocratic circles.

The literary work of Chaucer is conveniently, but not accurately, arranged in three different periods. While attached to the court, one of his duties was to entertain the king and his visitors in their leisure. French poems of love and chivalry were then in demand, and of these Chaucer had great store; but English had recently replaced French even at court, and King Edward and Queen Philippa, both patrons of art and letters, encouraged Chaucer to write in his native language. So he made translations of favorite poems into English, and wrote others in imitation of French models. These early works, the least interesting of all, belong to what is called the period of French influence.

Then Chaucer, who had learned the art of silence as well as of speech, was sent abroad on a series of diplomatic missions. In Italy he probably met the poet Petrarch (as we infer from the Prologue to the Clerk’s Tale) and became familiar with the works of Dante and Boccaccio. His subsequent poetry shows a decided advance in range and originality, partly because of his own growth, no doubt, and partly because of his better models. This second period, of about fifteen years, is called the time of Italian influence.

In the third or English period Chaucer returned to London and was a busy man of affairs; for at the English court, unlike those of France and Italy, a poet was expected to earn his pension by some useful work, literature being regarded as a recreation. He was in turn comptroller of customs and superintendent of public works; also he was at times well supplied with money, and again, as the political fortunes of his patron John of Gaunt waned, in sore need of the comforts of life. Witness his “Complaint to His Empty Purse,” the humor of which evidently touched the king and brought Chaucer another pension.

Two poems of this period are supposed to contain autobiographical material. In the Legend of Good Women he says:

And as for me, though that my wit be lytë,

On bokës for to rede I me delytë.

Again, in The House of Fame he speaks of finding his real life in books after his daily work in the customhouse is ended. Some of the “rekeninges” (itemized accounts of goods and duties) to which he refers are still preserved in Chaucer’s handwriting:

For whan thy labour doon al is,

And hast y-maad thy rekeninges,

In stede of reste and newë thinges

Thou gost hoom to thy hous anoon,

And, also domb as any stoon,

Thou sittest at another boke

Til fully dawsëd is thy loke,

And livest thus as an hermytë,

Although thine abstinence is lytë.

Such are the scanty facts concerning England’s first great poet, the more elaborate biographies being made up chiefly of guesses or doubtful inferences. He died in the year 1400, and was buried in St. Benet’s chapel in Westminster Abbey, a place now revered by all lovers of literature as the Poets’ Corner.

ON READING CHAUCER. Said Caxton, who was the first to print Chaucer’s poetry, “He writeth no void words, but all his matter is full of high and quick sentence.” Caxton was right, and the modern reader’s first aim should be to get the sense of Chaucer rather than his pronunciation. To understand him is not so difficult as appears at first sight, for most of the words that look strange because of their spelling will reveal their meaning to the ear if spoken aloud. Thus the word “leefful” becomes “leveful” or “leaveful” or “permissible.”

Next, the reader should remember that Chaucer was a master of versification, and that every stanza of his is musical. At the beginning of a poem, therefore, read a few lines aloud, emphasizing the accented syllables until the rhythm is fixed; then make every line conform to it, and every word keep step to the music. To do this it is necessary to slur certain words and run others together; also, since the mistakes of Chaucer’s copyists are repeated in modern editions, it is often necessary to add a helpful word or syllable to a line, or to omit others that are plainly superfluous.

This way of reading Chaucer musically, as one would read any other poet, has three advantages: it is easy, it is pleasant, and it is far more effective than the learning of a hundred specifications laid down by the grammarians.

As for Chaucer’s pronunciation, you will not get that accurately without much study, which were better spent on more important matters; so be content with a few rules, which aim simply to help you enjoy the reading. As a general principle, the root vowel of a word was broadly sounded, and the rest slurred over. The characteristic sound of a was as in “far”; e was sounded like a, i like e, and all diphthongs as broadly as possible,–in “floures” (flowers), for example, which should be pronounced “floorës.”

Another rule relates to final syllables, and these will appear more interesting if we remember that they represent the dying inflections of nouns and adjectives, which were then declined as in modern German. Final ed and es are variable, but the rhythm will always tell us whether they should be given an extra syllable or not. So also with final e, which is often sounded, but not if the following word begins with a vowel or with h. In the latter case the two words may be run together, as in reading Virgil. If a final e occurs at the end of a line, it may be lightly pronounced, like a in “China,” to give added melody to the verse.

Applying these rules, and using our liberty as freely as Chaucer used his, the opening lines of The Canterbury Tales would read something like this:

Whan that Aprille with his shoures sote

Whan that Apreelë with ‘is shoorës sohtë

The droghte of Marche hath perced to the rote,

The drooth of March hath paarcëd to the rohtëAnd bathed every veyne in swich licour,

And bahthëd ev’ree vyne in swech lecoor,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

Of whech varetu engendred is the floor;Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth

Whan Zephirus aik with ‘is swaite braith

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

Inspeerëd hath in ev’ree holt and haithThe tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

The tendre croopës, and th’ yoongë sonnë

Hath in the Ram his halfe cours y-ronne,

Hath in the Ram ‘is hawfë coors ironnë,And smale fowles maken melodye,

And smawlë foolës mahken malyodieë,

That slepen al the night with open ye

That slaipen awl the nicht with open eë(So priketh hem nature in hir corages)

(So priketh ‘eem nahtur in hir coorahgës)

Than longen folk to goon on pilgrimages.

Than longen folk to goon on peelgrimahgës.

EARLY WORKS OF CHAUCER. In his first period, which was dominated by French influence, Chaucer probably translated parts of the Roman de la Rose, a dreary allegorical poem in which love is represented as a queen-rose in a garden, surrounded by her court and ministers. In endeavoring to pluck this rose the lover learns the “commandments” and “sacraments” of love, and meets with various adventures at the hands of Virtue, Constancy, and other shadowy personages of less repute. Such allegories were the delight of the Middle Ages; now they are as dust and ashes. Other and better works of this period are The Book of the Duchess, an elegy written on the death of Blanche, wife of Chaucer’s patron, and various minor poems, such as “Compleynte unto Pitee,” the dainty love song “To Rosemunde,” and “Truth” or the “Ballad of Good Counsel.”

Characteristic works of the second or Italian period are The House of Fame, The Legend of Good Women, and especially Troilus and Criseyde. The last-named, though little known to modern readers, is one of the most remarkable narrative poems in our literature. It began as a retelling of a familiar romance; it ended in an original poem, which might easily be made into a drama or a “modern” novel.

The scene opens in Troy, during the siege of the city by the Greeks. The hero Troilus is a son of Priam, and is second only to the mighty Hector in warlike deeds. Devoted as he is to glory, he scoffs at lovers until the moment when his eye lights on Cressida. She is a beautiful young widow, and is free to do as she pleases for the moment, her father Calchas having gone over to the Greeks to escape the doom which he sees impending on Troy. Troilus falls desperately in love with Cressida, but she does not know or care, and he is ashamed to speak his mind after scoffing so long at love. Then appears Pandarus, friend of Troilus and uncle to Cressida, who soon learns the secret and brings the young people together. After a long courtship with interminable speeches (as in the old romances) Troilus wins the lady, and all goes happily until Calchas arranges to have his daughter brought to him in exchange for a captured Trojan warrior. The lovers are separated with many tears, but Cressida comforts the despairing Troilus by promising to hoodwink her doting father and return in a few days. Calchas, however, loves his daughter too well to trust her in a city that must soon be given over to plunder, and keeps her safe in the Greek camp. There the handsome young Diomede wins her, and presently Troilus is killed in battle by Achilles.

Such is the old romance of feminine fickleness, which had been written a hundred times before Chaucer took it bodily from Boccaccio. Moreover he humored the old romantic delusion which required that a lover should fall sick in the absence of his mistress, and turn pale or swoon at the sight of her; but he added to the tale many elements not found in the old romances, such as real men and women, humor, pathos, analysis of human motives, and a sense of impending tragedy which comes not from the loss of wealth or happiness but of character. Cressida’s final thought of her first lover is intensely pathetic, and a whole chapter of psychology is summed up in the line in which she promises herself to be true to Diomede at the very moment when she is false to Troilus:

“Allas! of me unto the worldës ende

Shal neyther ben ywríten nor y-songë

No good word; for these bookës wol me shende.

O, rollëd shal I ben on many a tongë!Thurghout the world my bellë shal be rongë,

And wommen moste wol haten me of allë.

Allas, that swich a cas me sholdë fallë!They wol seyn, in-as-much as in me is,

I have hem doon dishonour, weylawey!Al be I not the firste that dide amis,

What helpeth that to doon my blame awey?But since I see ther is no betre wey,

And that too late is now for me to rewé,

To Diomede, algate, I wol be trewé.”

THE CANTERBURY TALES. The plan of gathering a company of people and letting each tell his favorite story has been used by so many poets, ancient and modern, that it is idle to seek the origin of it. Like Topsy, it wasn’t born; it just grew up. Chaucer’s plan, however, is more comprehensive than any other in that it includes all classes of society; it is also more original in that it does not invent heroic characters but takes such men and women as one might meet in any assembly, and shows how typical they are of humanity in all ages. As Lowell says, Chaucer made use in his Canterbury Tales of two things that are everywhere regarded as symbols of human life; namely, the short journey and the inn. We might add, as an indication of Chaucer’s philosophy, that his inn is a comfortable one, and that the journey is made in pleasant company and in fair weather.

An outline of Chaucer’s great work is as follows. On an evening in springtime the poet comes to Tabard Inn, in Southwark, and finds it filled with a merry company of men and women bent on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Thomas à Becket in Canterbury.

After supper appears the jovial host, Harry Bailey, who finds the company so attractive that he must join it on its pilgrimage. He proposes that, as they shall be long on the way, they shall furnish their own entertainment by telling stories, the best tale to be rewarded by the best of suppers when the pilgrims return from Canterbury. They assent joyfully, and on the morrow begin their journey, cheered by the Knight’s Tale as they ride forth under the sunrise. The light of morning and of springtime is upon this work, which is commonly placed at the beginning of modern English literature.

As the journey proceeds we note two distinct parts to Chaucer’s record. One part, made up of prologues and interludes, portrays the characters and action of the present comedy; the other part, consisting of stories, reflects the comedies and tragedies of long ago. The one shows the perishable side of the men and women of Chaucer’s day, their habits, dress, conversation; the other reveals an imperishable world of thought, feeling, ideals, in which these same men and women discover their kinship to humanity. It is possible, since some of the stories are related to each other, that Chaucer meant to arrange the Canterbury Tales in dramatic unity, so as to make a huge comedy of human society; but the work as it comes down to us is fragmentary, and no one has discovered the order in which the fragments should be fitted together.

The Prologue is perhaps the best single fragment of the Canterbury Tales. In it Chaucer introduces us to the characters of his drama: to the grave Knight and the gay Squire, the one a model of Chivalry at its best, “a verray parfit gentil knight,” the other a young man so full of life and love that “he slept namore than dooth a nightingale”; to the modest Prioress, also, with her pretty clothes, her exquisite manners, her boarding-school accomplishments:

And Frensh she spak ful faire and fetisly,

After the scole of Stratford attë Bowë,

For Frensh of Paris was to hir unknowë.

In contrast to this dainty figure is the coarse Wife of Bath, as garrulous as the nurse in Romeo and Juliet. So one character stands to another as shade to light, as they appear in a typical novel of Dickens. The Church, the greatest factor in medieval life, is misrepresented by the hunting Monk and the begging Friar, and is well represented by the Parson, who practiced true religion before he preached it:

But Christës lore and his apostles twelvë

He taughte, and first he folwëd it himselvë.

Trade is represented by the Merchant, scholarship by the poor Clerk of Oxenford, the professions by the Doctor and the Man-of-law, common folk by the Yeoman, Frankelyn (farmer), Miller and many others of low degree.

Prominent among the latter was the Shipman:

Hardy he was, and wys to undertakë;

With many a tempest hadde his berd been shakë.

From this character, whom Stevenson might have borrowed for his Treasure Island, we infer the barbarity that prevailed when commerce was new, when the English sailor was by turns smuggler or pirate, equally ready to sail or scuttle a ship, and to silence any tongue that might tell tales by making its wretched owner “walk the plank.” Chaucer’s description of the latter process is a masterpiece of piratical humor:

If that he faught and hadde the hyer hond,

By water he sente hem hoom to every lond.

Some thirty pilgrims appear in the famous Prologue, and as each was to tell two stories on the way to Canterbury, and two more on the return, it is probable that Chaucer contemplated a work of more than a hundred tales. Only four-and-twenty were completed, but these are enough to cover the field of light literature in that day, from the romance of love to the humorous animal fable. Between these are wonder-stories of giants and fairies, satires on the monks, parodies on literature, and some examples of coarse horseplay for which Chaucer offers an apology, saying that he must let each pilgrim tell his tale in his own way.

A round dozen of these tales may still be read with pleasure; but, as a suggestion of Chaucer’s variety, we name only three: the Knight’s romance of “Palamon and Arcite,” the Nun’s Priest’s fable of “Chanticleer,” and the Clerk’s old ballad of “Patient Griselda.” The last-named will be more interesting if we remember that the subject of woman’s rights had been hurled at the heads of the pilgrims by the Wife of Bath, and that the Clerk told his story to illustrate his different ideal of womanhood.

THE CHARM OF CHAUCER. The first of Chaucer’s qualities is that he is an excellent story-teller; which means that he has a tale to tell, a good method of telling it, and a philosophy of life which gives us something to think about aside from the narrative. He had a profound insight of human nature, and in telling the simplest story was sure to slip in some nugget of wisdom or humor: “What wol nat be mote need be left,” “For three may keep counsel if twain be away,” “The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne,” “Ful wys is he that can himselven knowe,” The firste vertue, sone, if thou wilt lere, Is to restreine and kepen wel thy tonge.

There are literally hundreds of such “good things” which make Chaucer a constant delight to those who, by a very little practice, can understand him almost as easily as Shakespeare. Moreover he was a careful artist; he knew the principles of poetry and of story-telling, and before he wrote a song or a tale he considered both his subject and his audience, repeating to himself his own rule:

Ther nis no werkman, whatsoever he be,

That may bothe werkë wel and hastily:

This wol be doon at leysur, parfitly.

A second quality of Chaucer is his power of observation, a power so extraordinary that, unlike other poets, he did not need to invent scenes or characters but only to describe what he had seen and heard in this wonderful world. As he makes one of his characters say:

For certeynly, he that me made

To comen hider seydë me:

I shouldë bothë hear et see

In this place wonder thingës.

In the Canterbury Tales alone he employs more than a score of characters, and hardly a romantic hero among them; rather does he delight in plain men and women, who reveal their quality not so much in their action as in their dress, manner, or tricks of speech. For Chaucer has the glance of an Indian, which passes over all obvious matters to light upon one significant detail; and that detail furnishes the name or the adjective of the object. Sometimes his descriptions of men or nature are microscopic in their accuracy, and again in a single line he awakens the reader’s imagination,–as when Pandarus (in Troilus), in order to make himself unobtrusive in a room where he is not wanted, picks up a manuscript and “makes a face,” that is, he pretends to be absorbed in a story,

and fand his countenance

As for to loke upon an old romance.

A dozen striking examples might be given, but we shall note only one. In the Book of the Duchess the poet is in a forest, when a chase sweeps by with whoop of huntsman and clamor of hounds. After the hunt, when the woods are all still, comes a little lost dog:

Hit com and creep to me as lowë

Right as hit haddë me y-knowë,

Hild down his heed and jiyned his eres,

And leyde al smouthë doun his heres.

I wolde han caught hit, and anoon

Hit fleddë and was fro me goon.

Next to his power of description, Chaucer’s best quality is his humor, a humor which is hard to phrase, since it runs from the keenest wit to the broadest farce, yet is always kindly and human. A mendicant friar comes in out of the cold, glances about the snug kitchen for the best seat:

And fro the bench he droof awey the cat.

Sometimes his humor is delicate, as in touching up the foibles of the Doctor or the Man-of-law, or in the Priest’s translation of Chanticleer’s evil remark about women:

In principio Mulier est hominis confusio.

Madame, the sentence of this Latin is:

Woman is mannes joye and al his blis.

The humor broadens in the Wife of Bath, who tells how she managed several husbands by making their lives miserable; and occasionally it grows a little grim, as when the Maunciple tells the difference between a big and a little rascal. The former does evil on a large scale, and,

Lo! therfor is he cleped a Capitain;

But for the outlawe hath but small meynee,

And may not doon so gret an harm as he,

Ne bring a countree to so gret mischeef,

Men clepen him an outlawe or a theef.

A fourth quality of Chaucer is his broad tolerance, his absolute disinterestedness. He leaves reforms to Wyclif and Langland, and can laugh with the Shipman who turns smuggler, or with the worldly Monk whose “jingling” bridle keeps others as well as himself from hearing the chapel bell. He will not even criticize the fickle Cressida for deserting Troilus, saying that men tell tales about her, which is punishment enough for any woman. In fine, Chaucer is content to picture a world in which the rain falleth alike upon the just and the unjust, and in which the latter seem to have a liberal share of the umbrellas. He enjoys it all, and describes its inhabitants as they are, not as he thinks they ought to be. The reader may think that this or that character deserves to come to a bad end; but not so Chaucer, who regards them all as kindly, as impersonally as Nature herself.

So the Canterbury pilgrims are not simply fourteenth-century Englishmen; they are human types whom Chaucer met at the Tabard Inn, and whom later English writers discover on all of earth’s highways. One appears unchanged in Shakespeare’s drama, another in a novel of Jane Austen, a third lives over the way or down the street. From century to century they change not, save in name or dress. The poet who described or created such enduring characters stands among the few who are called universal writers.

* * * * *

CHAUCER’S CONTEMPORARIES AND SUCCESSORS

Someone has compared a literary period to a wood in which a few giant oaks lift head and shoulders above many other trees, all nourished by the same soil and air. If we follow this figure, Langland and Wyclif are the only growths that tower beside Chaucer, and Wyclif was a reformer who belongs to English history rather than to literature.

LANGLAND. William Langland (cir. 1332–1400) is a great figure in obscurity. We are not certain even of his name, and we must search his work to discover that he was, probably, a poor lay-priest whose life was governed by two motives: a passion for the poor, which led him to plead their cause in poetry, and a longing for all knowledge:

All the sciences under sonnë, and all the sotyle craftës,

I wolde I knew and couthë, kyndely in mynë hertë.

His chief poem, Piers Plowman (cir. 1362), is a series of visions in which are portrayed the shams and impostures of the age and the misery of the common people. The poem is, therefore, as the heavy shadow which throws into relief the bright picture of the Canterbury Tales.

For example, while Chaucer portrays the Tabard Inn with its good cheer and merry company, Langland goes to another inn on the next street; there he looks with pure eyes upon sad or evil-faced men and women, drinking, gaming, quarreling, and pictures a scene of physical and moral degradation. One must look on both pictures to know what an English inn was like in the fourteenth century.

Because of its crude form and dialect Piers Plowman is hard to follow; but to the few who have read it and entered into Langland’s vision—shared his passion for the poor, his hatred of shams, his belief in the gospel of honest work, his humor and satire and philosophy—it is one of the most powerful and original poems in English literature.

The working classes were beginning to assert themselves in this age, and to proclaim “the rights of man.” Witness the followers of John Ball, and his influence over the crowd when he chanted the lines:

When Adam delved and Eve span,

Who was then the gentleman?

Langland’s poem, written in the midst of the labor agitation, was the first glorification of labor to appear in English literature. Those who read it may make an interesting comparison between “Piers Plowman” and a modern labor poem, such as Hood’s “Song of the Shirt” or Markham’s “The Man with the Hoe.”

MALORY. Judged by its influence, the greatest prose work of the fifteenth century was the Morte d’Arthur of Thomas Malory (d. 1471). Of the English knight who compiled this work very little is known beyond this, that he sought to preserve in literature the spirit of medieval knighthood and religion. He tells us nothing of this purpose; but Caxton, who received the only known copy of Malory’s manuscript and published it in 1485, seems to have reflected the author’s spirit in these words:

“I according to my copy have set it in imprint, to the intent that noble men may see and learn the noble acts of chivalry, the gentle and virtuous deeds that some knyghts used in those days, by which they came to honour, and how they that were vicious were punished and put oft to shame and rebuke…. For herein may be seen noble chivalry, courtesy, humanity, hardness, love, friendship, cowardice, murder, hate, virtue and sin. Do after the good, and leave the evil, and it shall bring you to good fame and renommee.”

Malory’s spirit is further indicated by the fact that he passed over all extravagant tales of foreign heroes and used only the best of the Arthurian romances. [Footnote: For the origin of the Arthurian stories see above, “Geoffrey and the Legends of Arthur” in Chapter II. An example of the way these stories were enlarged is given by Lewis, Beginnings of English Literature, pp 73-76, who records the story of Arthur’s death as told, first, by Geoffrey, then by Layamon, and finally by Malory, who copied the tale from French sources. If we add Tennyson’s “Passing of Arthur,” we shall have the story as told from the twelfth to the nineteenth century.] These had been left in a chaotic state by poets, and Malory brought order out of the chaos by omitting tedious fables and arranging his material in something like dramatic unity under three heads: the Coming of Arthur with its glorious promise, the Round Table, and the Search for the Holy Grail:

“And thenne the kynge and al estates wente home unto Camelot, and soo wente to evensonge to the grete mynster, and soo after upon that to souper; and every knyght sette in his owne place as they were to forehand. Thenne anone they herd crakynge and cryenge of thonder, that hem thought the place shold alle to dryve. In the myddes of this blast entred a sonne beaume more clerer by seven tymes than ever they sawe daye, and al they were alyghted of the grace of the Holy Ghoost. Then beganne every knyghte to behold other, and eyther sawe other by theire semynge fayrer than ever they sawe afore. Not for thenne there was no knyght myghte speke one word a grete whyle, and soo they loked every man on other, as they had ben domb. Thenne ther entred into the halle the Holy Graile, covered with whyte samyte, but ther was none myghte see hit, nor who bare hit. And there was al the halle fulfylled with good odoures, and every knyght had suche metes and drynkes as he best loved in this world. And when the Holy Grayle had be borne thurgh the halle, thenne the holy vessel departed sodenly, that they wyste not where hit becam….

“’Now,’ said Sir Gawayne, ‘we have ben served this daye of what metes and drynkes we thoughte on, but one thynge begyled us; we myght not see the Holy Grayle, it was soo precyously coverd. Therfor I wil mak here avowe, that to morne, withoute lenger abydyng, I shall laboure in the quest of the Sancgreal; that I shalle hold me oute a twelve moneth and a day, or more yf nede be, and never shalle I retorne ageyne unto the courte tyl I have sene hit more openly than hit hath ben sene here.’… Whan they of the Table Round herde Syr Gawayne saye so, they arose up the most party and maade suche avowes as Sire Gawayne had made.”

Into this holy quest sin enters like a serpent; then in quick succession tragedy, rebellion, the passing of Arthur, the penitence of guilty Launcelot and Guinevere. The figures fade away at last, as Shelley says of the figures of the Iliad, “in tenderness and inexpiable sorrow.”

As the best of Malory’s work is now easily accessible, we forbear further quotation. These old Arthurian legends, the common inheritance of all English-speaking people, should be known to every reader. As they appear in Morte d’Arthur they are notable as an example of fine old English prose, as a reflection of the enduring ideals of chivalry, and finally as a storehouse in which Spenser, Tennyson and many others have found material for some of their noblest poems.

CAXTON. William Caxton (d. 1491) is famous for having brought the printing press to England, but he has other claims to literary renown. He was editor as well as printer; he translated more than a score of the books which came from his press; and, finally, it was he who did more than any other man to fix a standard of English speech.

In Caxton’s day several dialects were in use, and, as we infer from one of his prefaces, he was doubtful which was most suitable for literature or most likely to become the common speech of England. His doubt was dissolved by the time he had printed the Canterbury Tales and the Morte d’Arthur. Many other works followed in the same “King’s English”; his successor at the printing press, Wynkyn de Worde, continued in the same line; and when, less than sixty years after the first English book was printed, Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament had found its way to every shire in England, there was no longer room for doubt that the East-Midland dialect had become the standard of the English nation. We have been speaking and writing that dialect ever since.

The story of how printing came to England, not as a literary but as a business venture, is a very interesting one. Caxton was an English merchant who had established himself at Bruges, then one of the trading centers of Europe. There his business prospered, and he became governor of the Domus Angliae, or House of the English Guild of Merchant Adventurers. There is romance in the very name. With moderate wealth came leisure to Caxton, and he indulged his literary taste by writing his own version of some popular romances concerning the siege of Troy, being encouraged by the English princess Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy, into whose service he had entered.

Copies of his work being in demand, Caxton consulted the professional copyists, whose beautiful work we read about in a remarkable novel called The Cloister and the Hearth. Then suddenly came to Bruges the rumor of Gutenberg’s discovery of printing from movable types, and Caxton hastened to Germany to investigate the matter, led by the desire to get copies of his own work as cheaply as possible. The discovery fascinated him; instead of a few copies of his manuscript he brought back to Bruges a press, from which he issued his Recuyell of the Historyes of Troy (1474), which was probably the first book to appear in English print. Quick to see the commercial advantages of the new invention, Caxton moved his printing press to London, near Westminster Abbey, where he brought out in 1477 his Dictes and Sayinges of the Philosophers, the first book ever printed on English soil.

From the very outset Caxton’s venture was successful, and he was soon busy in supplying books that were most in demand. He has been criticized for not printing the classics and other books of the New Learning; but he evidently knew his business and his audience, and aimed to give people what they wanted, not what he thought they ought to have. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, Mandeville’s Travels, Æsop’s Fables, parts of the Æneid, translations of French romances, lives of the saints (The Golden Legend), cookbooks, prayer books, books of etiquette,–the list of Caxton’s eighty-odd publications becomes significant when we remember that he printed only popular books, and that the titles indicate the taste of the age which first looked upon the marvel of printing.

POPULAR BALLADS. If it be asked, “What is a ballad?” any positive answer will lead to disputation. Originally the ballad was probably a chant to accompany a dance, and so it represents the earliest form of poetry. In theory, as various definitions indicate, it is a short poem telling a story of some exploit, usually of a valorous kind. In common practice, from Chaucer to Tennyson, the ballad is almost any kind of short poem treating of any event, grave or gay, in any descriptive or dramatic way that appeals to the poet.

For the origin of the ballad one must search far back among the social customs of primitive times. That the Anglo-Saxons were familiar with it appears from the record of Tacitus, who speaks of their carmina or narrative songs; but, with the exception of “The Fight at Finnsburgh” and a few other fragments, all these have disappeared.

During the Middle Ages ballads were constantly appearing among the common people, but they were seldom written, and found no standing in polite literature. In the eighteenth century, however, certain men who had grown weary of the formal poetry of Pope and his school turned for relief to the old vigorous ballads of the people, and rescued them from oblivion. The one book to which, more than any other, we owe the revival of interest in balladry is Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765).

The best of our ballads date in their present form from the fifteenth or sixteenth century; but the originals were much older, and had been transmitted orally for years before they were recorded on manuscript. As we study them we note, as their first characteristic, that they spring from the unlettered common people, that they are by unknown authors, and that they appear in different versions because they were changed by each minstrel to suit his own taste or that of his audience.

A second characteristic is the objective quality of the ballad, which deals not with a poet’s thought or feeling (such subjective emotions give rise to the lyric) but with a man or a deed. See in the ballad of “Sir Patrick Spence” (or Spens) how the unknown author goes straight to his story:

The king sits in Dumferling towne,

Drinking the blude-red wine:

“O whar will I get guid sailor

To sail this schip of mine?”Up and spak an eldern knicht,

Sat at the king’s richt kne:

“Sir Patrick Spence is the best sailor

That sails upon the se.”

There is a brief pause to tell us of Sir Patrick’s dismay when word comes that the king expects him to take out a ship at a time when she should be riding to anchor, then on goes the narrative:

“Mak hast, mak haste, my mirry men all,

Our guid schip sails the morne.”“O say na sae, my master deir,

For I feir a deadlie storme:“Late, late yestreen I saw the new moone

Wi the auld moone in hir arme,

And I feir, I feir, my deir master,

That we will cum to harme.”

At the end there is no wailing, no moral, no display of the poet’s feeling, but just a picture:

O lang, lang may the ladies stand,

Wi thair gold kems in their hair,

Waiting for thair ain deir lords,

For they’ll se thame na mair.Haf owre, haf owre to Aberdour,

It’s fiftie fadom deip,

And thair lies guid Sir Patrick Spence,

Wi the Scots lords at his feit.

Directness, vigor, dramatic action, an ending that appeals to the imagination,–most of the good qualities of story-telling are found in this old Scottish ballad. If we compare it with Longfellow’s “Wreck of the Hesperus,” we may discover that the two poets, though far apart in time and space, have followed almost identical methods.

Other good ballads, which take us out under the open sky among vigorous men, are certain parts of “The Gest of Robin Hood,” “Mary Hamilton,” “The Wife of Usher’s Well,” “The Wee Wee Man,” “Fair Helen,” “Hind Horn,” “Bonnie George Campbell,” “Johnnie O’Cockley’s Well,” “Catharine Jaffray” (from which Scott borrowed his “Lochinvar”), and especially “The Nutbrown Mayde,” sweetest and most artistic of all the ballads, which gives a popular and happy version of the tale that Chaucer told in his “Patient Griselda.”

* * * * *

SUMMARY. The period included in the Age of Chaucer and the Revival of Learning covers two centuries, from 1350 to 1550. The chief literary figure of the period, and one of the greatest of English poets, is Geoffrey Chaucer, who died in the year 1400. He was greatly influenced by French and Italian models; he wrote for the middle and upper classes; his greatest work was The Canterbury Tales.

Langland, another poet contemporary with Chaucer, is famous for his Piers Plowman, a powerful poem aiming at social reform, and vividly portraying the life of the common people. It is written in the old Saxon manner, with accent and alliteration, and is difficult to read in its original form.

After the death of Chaucer a century and a half passed before another great writer appeared in England. The time was one of general decline in literature, and the most obvious causes were: the Wars of the Roses, which destroyed many of the patrons of literature; the Reformation, which occupied the nation with religious controversy; and the Renaissance or Revival of Learning, which turned scholars to the literature of Greece and Rome rather than to English works.

In our study of the latter part of the period we reviewed: (1) the rise of the popular ballad, which was almost the only type of literature known to the common people. (2) The work of Malory, who arranged the best of the Arthurian legends in his Morte d’Arthur. (3) The work of Caxton, who brought the first printing press to London, and who was instrumental in establishing the East-Midland dialect as the literary language of England.

SELECTIONS FOR READING. Typical selections from all authors of the period are given in Manly, English Poetry, and English Prose; Newcomer and Andrews, Twelve Centuries of English Poetry and Prose; Ward, English Poets; Morris and Skeat, Specimens of Early English.

Chaucer’s Prologue, Knight’s Tale, and other selections in Riverside Literature, King’s Classics, and several other school series. A good single-volume edition of Chaucer’s poetry is Skeat, The Student’s Chaucer (Clarendon Press). A good, but expensive, modernized version is Tatlock and MacKaye, Modern Reader’s Chaucer (Macmillan).

Metrical version of Piers Plowman, by Skeat, in King’s Classics; modernized prose version by Kate Warren, in Treasury of English Literature (Dodge).

Selections from Malory’s Morte d’Arthur in Athenæum Press Series (Ginn and Company); also in Camelot Series. An elaborate edition of Malory with introduction by Sommer and an essay by Andrew Lang (3 vols., London, 1889); another with modernized text, introduction by Rhys, illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley (London, 1893).

The best of the old ballads are published in Pocket Classics, and in Maynard’s English Classics; a volume of ancient and modern English ballads in Ginn and Company’s Classics for Children; Percy’s Reliques, in Everyman’s Library. Allingham, The Ballad Book; Hazlitt, Popular Poetry of England; Gummere, Old English Ballads; Gayley and Flaherty, Poetry of the People; Child, English and Scottish Popular Poetry (5 vols.); the last-named work, edited and abridged by Kittredge, in one volume.

BIBLIOGRAPHY. The following works have been sifted from a much larger number dealing with the age of Chaucer and the Revival of Learning. More extended works, covering the entire field of English history and literature, are listed in the General Bibliography.

HISTORY. Snell, the Age of Chaucer; Jusserand, Wayfaring Life in the Fourteenth Century; Jenks, In the Days of Chaucer; Trevelyan, In the Age of Wyclif; Coulton, Chaucer and His England; Denton, England in the Fifteenth Century; Green, Town Life in the Fifteenth Century; Einstein, The Italian Renaissance in England; Froissart, Chronicles; Lanier, The Boy’s Froissart.

LITERATURE. Ward, Life of Chaucer (English Men of Letters Series); Kittredge, Chaucer and His Poetry (Harvard University Press); Pollard, Chaucer Primer; Lounsbury, Studies in Chaucer; Lowell’s essay in My Study Windows; essay by Hazlitt, in Lectures on the English Poets; Jusserand, Piers Plowman; Roper, Life of Sir Thomas More.

FICTION AND POETRY. Lytton, Last of the Barons; Yonge, Lances of Lynwood; Scott, Marmion; Shakespeare, Richard II, Henry IV, Richard III; Bates and Coman, English History Told by English Poets.