By M. K. Van Rensselaer.

It is probable that one of the oldest existing packs is the Tarot pack now preserved in the Cabinet des Estampes in Paris. Others discovered in the back of a book in Florence in 1910, also Tarots, have not been open to the inspection of students. They are valued at two thousand dollars, but the pack is not complete, nor on record, so the cards painted for Charles VI may still claim to be the oldest known. The débris of this pack was also discovered in the binding of a book of the fifteen century. The heraldic devices on the cards and the detail of the costumes, which are essentially French, point to their having been produced in the time of Charles VI. The robes, beards, etc., of three of the Kings are similar to the portraits of Charles or his courtiers. The velvet hats are surmounted with crowns and the robes are trimmed with ermine. The dress of the Knaves corresponds with that of the pages, or else with that of the sergents d’Armes of the day, while the Queens are dressed like the portrait of Isabella of Bavaria. The court cards of the fourth suit show a marked contrast to the richly bedecked ones of the three other suits, for the figures are habited like savages, which is supposed to recall a fête given on the occasion of the marriage of one of the queen’s maids of honour to the Chevalier de Vermandois, that had such a horrible termination.

Charles VI had had attacks of mania, but was at that time more reasonable. Hugonin de Janzay, one of his favourites, planned to entertain him by inducing him to take part in a mummery, for which the king and five other men were to be dressed as savages, and were to enter the fête to surprise the guests. The party were dressed in linen soaked with tar and covered with fur, so were completely disguised. They rushed into the ballroom shouting and rattling their chains, when the Duc D’Orleans, brother of the king, seized a torch from an attendant to look more closely at the strangers, and by mischance set the inflammable clothes on fire. Most of the men were chained together and could not escape, but one of them freed himself and saved his own life by plunging into a cistern of water which was placed in the buttery for the purpose of rinsing the drinking cups.

The king, who was standing at a little distance talking to the Duchess de Beri, was saved by that lady, who, with great presence of mind, wrapped her velvet cloak around her royal master. This gruesome incident brought on another attack of mania, that lasted until his death on the 21st of October, 1422, after a reign of forty-two years. It is presumed by M. Paul la Croix, in his essay on “Cartes a Jouer” (1873), that this celebrated incident was perpetuated in the French cards that he thinks were invented and painted at about that time.

The fragments of the second pack, that apparently belong to the same period, closely resemble those with which we are familiar, since they are not Tarots but bear the pips invented by the French, and M. la Croix states (page 241) that he “credits the tradition declaring that these particular cards are the first Piquet pack, and that these were the original cards that dethroned the Tarots of the Italians to become the favorites of the French nation.”

These French pips were afterwards adopted by the less ingenious English, while the Germans invented devices of their own, called Grünen, Eicheln, Herzen, and Shellen, at about the same period. Although the Spaniards remained faithful to the Tarots, they discarded the Atout part of the pack, retaining only the suit cards with the pips of Cups, Money, Swords, and Staves. The emblems adopted in the several countries nearly five hundred years ago (when a wave of card playing seems to have swept over Europe), have retained their hold on the affections of those who adopted the individual devices, for each nation still clings to the pips that were then chosen, and it is only by degrees that the French designs are emigrating to different parts of the world.

The “Jesse” pack of cards, now to be seen in Paris, are painted on cardboard, and the figures are dressed in the fashions of the day. The emblems recall the heraldic tokens of two of the courtiers of Charles VI, as well as the one identified with one of the most beautiful and learned women of her day. It is said that the invention of these pips was due to the anxiety of Queen Isabella and her ministers to divert the unfortunate monarch, so as to prevent his interfering with their schemes.

It was with the alteration of the pips, the adoption of Coeurs (Hearts), Carreaux (Diamonds), Trèfles (Clubs), and Piques (Spades), the distinctive use of red and black unmingled with other colours, and the discarding of the fourth court card, together with the Joker, and the Atout part of the old pack, that the fortune-telling Book of Thoth became transformed into a set of toys or gambling instruments. It is little wonder that their original intention, purpose, and history became obliterated and finally almost forgotten, so that when a French writer ventured to state that cards were part of the Egyptian mysteries he was treated as a foolish dreamer.

The invention of the French pips is attributed to two persons, both of them courtiers of the king, who probably worked together to produce a simple and convenient set of devices that should be easily recognised and as well adapted for playing, as were the original Tarots suited for divining the lives and characteristics of mankind. One of the inventors of the French pips was Etienne Vignolles, whose nickname was La Hire, and this name has been found on some of the old cards, as if he wished to be perpetuated in this way, and not as the brave old soldier who was well versed in chivalric customs, and who, according to historians, had always his sword drawn against the English. The second person to whom is credited the invention of the Piquet pack is Etienne Chevalier, secretary to the king, and his treasurer, who was noted for his original and inventive genius and his quick wit. It is more than probable that to his facile pencil the new designs should be attributed. The men who formulated the rules of the game for which they invented the cards must have been clever, as it is arranged with such care that these rules have remained practically unaltered for five hundred years, and Piquet is still a favourite in men’s clubs and the best tête-a-tête game known.

The Piquet pack contains five pip cards, Ace, Seven, Eight, Nine, and Ten, with three court cards, King, Queen, and Knave, called by the French names of Le Roi, La Reine, and Le Valet or varlet. With this handful of cards we are all familiar. Here was a great modification of the old suits with their heraldic devices. The Cavalier of the Tarot pack was discarded, thus reducing the court cards to three instead of four, while five of the pip cards were also omitted. The game was thoroughly scientific, needing close attention and discretion even with the curtailed pack of cards. It showed the soldier’s hand in its stratagem, and that of the artist in its simple colours.

The king’s banker was Jacques Cœur, whose beautiful palace in Bourges shows a pun on his name in every lintel, door or window where a heart is cut in stone or wood to remind one of the owner. Tradition states that it was in honour of Jacques Cœur that his heraldic emblem, Coeurs (Hearts), was placed on the cards to perpetuate his memory, to the exclusion of that of his patron, Mercury, the god of merchants.

The Money emblem was changed to Carreaux (Diamonds). This device may have been inspired by the little lozenge panes of glass in the windows of Cœur’s palace, or by the tiles in the floors, or perhaps by “les fers de fiche,” which would have retained the original idea of the “divining arrows” from which the old cards came. M. la Croix says: “The Sword of the ancients became Pique (Spade), to do honour to the two soldier brothers, Jean and Gaspard Bureau.” The Trèfle (Club) was the heraldic device of Agnes Sorel, a greatly accomplished woman who displaced the queen in the affections of her husband. Sorel is the French for what we call shamrock or clover, and was a pun on the name of the lady.

M. la Croix thinks that these cards were devised some time between the years 1420 and 1440. If so, they could only have been born at the very end of the mad king’s life.

The distinctive marks of the French pack are the two dominating colours, red and black, that strongly contrast with the various and mingled colours seen in the Tarots. The reason for simplifying the pips in this way is not recorded, although the change makes it much easier for players and was a clever idea, but no sharp division like this is called for when playing the game of Piquet (or little Pique), for which these cards were primarily used. It was probably intended to simplify the work of the card maker, as it demanded only the two colours commonly used by printers, black and red.

It was about the year 1785, over three hundred years after the French had become accustomed to their new cards, and had entirely forgotten that there were any others, that Court de Gebelin, a French writer, published his essay on Tarots, which he calls “that strange collection of unbound leaves that are the parents of all modern playing cards.” It is entitled “Extràit du Monde Primative Analysé et comparé avec le Monde Moderne, Tome I, Du Jeu des Tarots.”

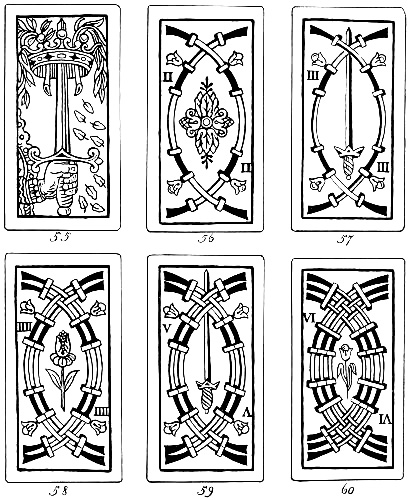

Early Italian Tarots

Pip Cards of the Sword Suit

The account begins with the announcement that the origin of the Tarots and their allegories will be traced and explained, as well as their connection with the cards of the day. The essay being in French, a free translation with necessary omissions must be given, while the curious are referred to the original. M. de Gebelin begins:

“If it were announced that one of the ancient books of the early Egyptians that contained most interesting information had escaped the flames that consumed their superb libraries, every one would doubtless be anxious to see such a precious and rare work. If added to this information it was stated that the leaves of this book were scattered over Europe, and that for centuries they had been in the hands of all the world, surprise and incredulity would greet the suggestion. Yet when, to crown all, it was realized that no one had even suspected the connection of the scattered pages in their possession with those of Egyptian mysteries, nor had any person deciphered a line on them, and that the fruit of an exquisite wisdom is to-day regarded as a collection of extravagant pictures without any significance, the world would be surprised at its own supineness or ignorance. Despite incredulity on these points, a great Egyptian book, the sole survivor of a valuable library, is still in existence, and, what is more strange, this book is so universally used and seems to be so insignificant that no savant has condescended to study its unbound pages, nor has any student suspected its illustrious origin. Composed of seventy-eight leaves that are divided into five classes, this book is, in one word, what is commonly known as the Tarot pack of cards. Of ancient origin, the bizarre pictures that they display do not betray the intention or motive for assembling together such peculiar figures and emblems. These pictures, that seem to be incongruously mingled, call for an answer to the enigma, and they should not be treated as trifles or merely for amusement.” Such is the opinion of a scholar who lived over one hundred years ago, and this opinion has survived the ridicule, abuse, and disdain showered on de Gebelin after he had pointed out that the Tarots were in truth the Book of Thoth Hermes Trismegistus.

There is only one spot in the world where these cards remain in their pristine condition and are played with to-day, and where they are offered for sale, and it is interesting to note that it is close to the place where the worship of Thoth first made its appearance in Europe.

The Tarots are now used for playing several games, and these, if analysed, will show marks of the ancient mysteries. Through them can be traced not only a birthplace, but a history declared by de Gebelin to hark back to the borderland of civilization. He points out that the writers of his day have confined their studies to French cards used in Paris, when they were looking for the origin of playing cards, entirely ignoring, or at least never referring to, the Tarots, of which probably they had never heard.

The history of French cards was not hard to relate, since it goes back little over three hundred years. There is a record of their birth, and, as has been mentioned, there are survivors of the original pack now to be seen in Les Cabinet des Estampes in Paris, which display Hearts, Diamonds, Clubs, and Spades.

Merlin, Chatto, Singer, and Breitkopf look farther afield than de Gebelin’s predecessors, whose writings are now forgotten, but all of them, while acknowledging that the images or the pips of the Tarots with which they are familiar have some connection with an old condition of affairs, fail to trace it, since no reliable historical or legal record of cards that are called “Playing Cards” can be discovered prior to the Middle Ages, so they assumed that cards could not have existed before that date, but the possibility that they might have lived and flourished under another name is overlooked.

These authorities acknowledge that the shape, the sequence, and the grouping of the Tarots display system, which they decide is interesting but incomprehensible, yet they fail to unravel the significance of these arrangements. They touch upon the strange resemblance of various figures and their value in the game of L’Ombre (The Man) to the civil law, philosophy, and religion of the ancient Romans, Greeks, or Egyptians. Mr. Singer points to one of the Atouts that he says “resembles the attributes of Osiris,” and other cards impress him as recalling those of Mercury, as well as other mythological personages that he writes “seem to be found among the Atouts.” But all the authors arrest themselves at this point without inquiring if these ancient gods whom they recognised were placed with intention or by chance on the cards, and, although they concede that the cards were used for divining purposes, they fail to connect them distinctly with the mysteries of past ages.

De Gebelin declares that “the Tarots could only be the outcome of the work of sages,” and that “these cards were intended for the use of initiates and not for gamblers.” He alone pierces the mystery of the origin of the Tarots, while the others content themselves with supposing that cards sprang in their present form into use precisely as Minerva emerged fully equipped from Jove’s head; they write that cards had no existence, no form, and no record, previous to those accorded to them about the thirteenth century.

To call an antagonist “a dreamer” or “a fool” is an unconvincing form of argument. To declare that a proposition is untrue because it is presented for the first time and has not been looked into is absurd; so to-day, over one hundred and twenty-five years after Court de Gebelin spread his pearls before the uncomprehending students of Playing Card lore, it may be well to recapitulate his theories and study his conclusions with minds opened by latter-day revelations of the ancient rites, mysteries, and cults, and not to reject them without investigation.

*******

This is taken from Prophetical, Educational and Playing Cards.

Copyright © D. J. McAdam· All Rights Reserved