(This is taken from W. Roberts' The Book-Hunter in London.)

The bookselling and book-hunting annals of the district which starts with St. Paul's, and terminates at Charing Cross, might occupy a goodly-sized volume. We must of necessity be brief, chiefly because both Paternoster Row and St. Paul's Churchyard have been, for the most part, book-publishing rather than second-hand bookselling localities. As a literary highway, Paternoster Row is of considerable antiquity, for Robert Rikke, a paternoster-maker and citizen, had a shop here in the time of Henry IV., and there can be no question that its name originated from the fact that it was at a very early period the residence of the makers of paternosters, or prayer-beads. Before the Great Fire of 1666, Paternoster Row was not much of a bookselling centre, for it was inhabited chiefly by mercers, silkmen, and lacemen, whose shops were a fashionable resort of the gentry who resided at that time in the immediate vicinity. After the Fire, the Row gradually became famous for its booksellers, or rather publishers, who resided at first near the east end, and whose large warehouses were 'well situated for learned and studious men's access thither, being more retired and private.' Although the book-annals of Paternoster Row chiefly deal with matters subsequent to the Great Fire, there were many publishers and booksellers there over a hundred years before that calamity. In and about 1558 there were, for example, two of the fraternity here established—Richard Lant and Henry Sutton, the latter's shop being at the sign of the Black Morion. For over twenty years, 1565 to 1587, Henry Denham was at the Star in Paternoster Row, whence he issued, among a large number of other books, George Turberville's 'Epitaphs, Epigrams, Songs, and Sonnets' in 1570.

The last century, however, witnessed the rise of Paternoster Row as a publishing locality. From 1678 and onwards book-auctions were held at the Hen and Chickens at nine in the morning; at the Golden Lion over against the Queen's Head Tavern, Paternoster Row, at nine in the morning and two in the afternoon, and at other places both in the Row and in its numerous tributaries, such as Ivy Lane, Ave Maria Lane, etc. Although some of the earliest book-auctions held in this country took place in the immediate vicinity of Paternoster Row, and although it had attained a world-wide celebrity as a publishing centre, it has very few interesting records as a second-hand bookselling locality. Awnsham and John Churchill were located at the Black Swan in 1700; William Taylor, the publisher of 'Robinson Crusoe,' 1719, was here at the sign of the Ship early in the last century, and was succeeded by Thomas Longman in 1725, the present handsome pile of buildings, erected in 1863, being on the original spot occupied in part by the founder of the firm. The Longmans had a second-hand department attached to their house in the early part of the present century, as we have already seen. Others which may be here mentioned as being connected with the Row are Baldwin and Cradock; and Ralph Griffiths, of the 'Dunciad'—'those significant emblems, the owl and long-eared animal, which Mr. Griffiths so sagely displays for the mirth and information of mankind'—for whom Goldsmith wrote reviews in a miserable garret. The last firm of second-hand booksellers of note who thrived in Paternoster Row was that of William Baynes and Son; and the last of the race is still remembered by the older generation of book-collectors, with his old-time appearance in frills and gaiters. In 1826 Baynes published one of the most remarkable catalogues (254 pages) of books printed in the fifteenth century which has ever appeared. It is full of extremely valuable bibliographical information. For many years John Wheldon, the natural history bookseller, had a shop, chiefly for the sale of back numbers of periodicals, at 4, Paternoster Row (as well as in Great Queen Street), and this little shop subsequently passed into the tenancy of Jesse Salisbury, who was there until six or seven years ago. The Chapter Coffee-house, where so many important publishing schemes have been mooted and carried out, still lingers in the Row, but modernized out of all recognition.

The chief interest of St. Paul's Churchyard as a book locality centres itself in the publishing rather than the second-hand bookselling phase. One of our earliest printer-publishers, Julian Notary, was 'dwellynge in powles chyrche yarde besyde ye weste dore by my lordes palyes' in 1515, his shop sign being the Three Kings. At the sign of the White Greyhound, in St. Paul's Churchyard, the first editions of Shakespeare's 'Venus and Adonis' and 'Rape of Lucrece' were published by John Harrison; at the Fleur de Luce and the Crown appeared the first edition of the 'Merry Wives of Windsor'; at the Green Dragon the first edition of the 'Merchant of Venice'; at the Fox the first edition of 'Richard II.'; whilst the first editions of 'Richard III.,' 'Troilus and Cressida,' 'Titus Andronicus,' and 'Lear' all bear Churchyard imprints.

Not only were there very many booksellers' shops around the Yard, but at the latter part of the sixteenth century bookstalls started up, first at the west, and subsequently at the other doors of the cathedral. From a letter addressed by Sir Clement Edmonds, March 28, 1620, to the Lord Mayor, we gather that two houses were erected at the west gate of St. Paul's without the sanction of the authorities, and these were ordered to be removed, as were also certain 'sheds or shops that were being erected near the same place.' A chief portion of the stock of these shops and stalls would naturally be devotional books of various descriptions. That these books were not always to be relied on we infer from an amusing anecdote in the Harleian manuscripts, related by Sir Nicholas L'Estrange, to the effect that 'Dr. Us[s]her, Bishop of Armath, having to preach at Paules Crosse, and passing hastily by one of the stationers, called for a Bible, and had a little one of the London edition given him out, but when he came to looke for his text, that very verse was omitted in the print.'

Mr. Pepys' bookseller, Joshua Kirton, was at the sign of the King's Arms. Writing under date November 2, 1660, Pepys chronicles: 'In Paul's Churchyard I called at Kirton's, and there they had got a masse book for me, which I bought, and cost me 12s., and, when I come home, sat up late and read in it with great pleasure to my wife, to hear that she was long ago acquainted with it.' Kirton was one of the most extensive sufferers of the bookselling fraternity in the Great Fire; from being a substantial tradesman with about £8,000 to the good, he was made £2,000 or £3,000 'worse than nothing.' The destruction of books and literary property generally, in and around St. Paul's, in this fire was enormous, Pepys calculating it at about £150,000, and Evelyn putting it at £200,000, or, in other words, about one million sterling as represented by our money of to-day. Evelyn tells us that soon after the fire had subsided the other trades went on as merrily as before, 'only the poor booksellers have been indeed ill-treated by Vulcan; so many noble impressions consumed by their trusting them to ye churches.'

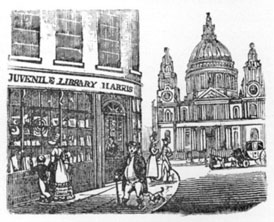

One of the most considerable of the Churchyard booksellers after the Great Fire was Richard Chiswell, the father or progenitor of a numerous family of bibliopoles. John Dunton, indeed, describes him as well deserving of the title of 'Metropolitan Bookseller of England, if not of all the world.' He was born in 1639, and died in 1711. In 1678 he sold, in conjunction with John Dunmore, another bookseller, the libraries of Dr. Benjamin Worsley and two other eminent men. At St. Paul's Coffee-house, which stood at the corner of the entrance from St. Paul's Churchyard to Doctors' Commons, the library of Dr. Rawlinson was, in 1711, sold—'at a prodigious rate,' according to Thoresby—in the evening after dinner. Although not quite à propos of our subject, we can scarcely help mentioning the name of so celebrated a Churchyard publisher as John Newbery, who lived at No. 65, the original site being now covered by the buildings of the R.T.S.; his successors, Griffith and Farran, were at No. 81 until the year 1889, when they moved westward. F. and C. Rivington were at No. 62 for many years, as Peter Pindar tells us:

A mere list of the Churchyard booksellers would fill a goodly-sized volume. In addition to those already mentioned, one of the most famous and successful families who resided here were the Knaptons, where, during the first three quarters of the last century, they built up an enormous trade, and were succeeded by Robert Horsfield, who carried on the business in Ludgate Street, and died in 1798. We possess one of the interesting catalogues of James and John Knapton, whose shop was at the sign of the Crown. It runs to twenty pages octavo, and enumerates an extraordinary variety of literature. The books written and sermons preached by right reverends and reverends occupy the first five pages, arranged according to the authors' names; and then follow the works of ordinary, commonplace mortals, sermons and Aphra Behn's romances, Mr. Dryden's plays and the 'Whole Duty of Man' appearing cheek-by-jowl.

The most important contribution to the earlier history of bookselling appeared from St. Paul's Churchyard in the shape of Robert Clavell's 'General Catalogue of Books printed in England since the Dreadful Fire, 1666, to the End of Trinity Term, 1676.' This catalogue was continued every term till 1700, and includes an abstract of the bills of mortality. The books are classified under their respective headings of divinity, history, physic and surgery, miscellanies, chemistry, etc., the publisher's name in each case being given. Dunton describes Clavell as 'an eminent bookseller' and 'a great dealer,' whilst Dr. Barlow, Bishop of Lincoln, distinguished him by the term of 'the honest bookseller.' Clavell's shop was at the sign of the Stag's Head, whilst his partner in many of his projects was Henry Brome, of the Sun, also in the Churchyard.

Joseph Johnson, the Dry Bookseller of Beloe, demands a short notice here. He was born at Liverpool in 1738, and after serving an apprenticeship with George Keith, Gracechurch Street, began business for himself on Fish Street Hill, which, being in the track of the medical students at the hospitals in the Borough, was a promising locality. After some years here, he removed to Paternoster Row, where he had as partners first a Mr. Davenport, and then John Payne; the house and stock were destroyed by fire in 1770, after which he removed to St. Paul's Churchyard, where he continued until his death in 1809, the father of the trade. He was a considerable publisher, and 'two poets of great modern celebrity were by him first introduced to the publick—Cowper and Darwin.' Whilst at Fish Street Hill he took over the stock of John Ward, of which he issued a catalogue.

Ludgate Hill to a certain degree not unnaturally secured a little of the 'bookish' brilliancy which diffused itself round and about the Churchyard. The highway to the cathedral was naturally a good business quarter, and there can be very little doubt that some of the stalls or booths, which formed a sort of middle row in Ludgate, were occupied by stationers and booksellers, who are not usually indifferent to the advantages of a good thoroughfare. It never, however, came up to St. Paul's Churchyard, either as a publishing or as a bookselling locality; but many retailers were here during the latter part of the last century. Queen Charlotte, wife of George III., is reported by Robert Huish to have said to Mrs. Delany: 'You cannot think what nice books I pick up at bookstalls, or how cheap I buy them.' The Rev. Dr. Croby, in his 'Life of George IV.,' tells us that Queen Charlotte was in the habit of paying visits, in company with some lady-in-waiting, to Holywell Street and Ludgate Hill, 'where second-hand books were exposed for sale during the last half of the eighteenth century.' During the earlier part of this period, among the booksellers of note in Ludgate Street were Robert Horsfield, William Johnston, and Richard Ware (who was a considerable adventurer in new publications). The business established at about the same period and in the same locality by Richard Manley, was considerably extended by John Pridden (1728-1807). The libraries of many eminent and distinguished characters passed through his hands, Nichols tells us. His offers in purchasing them were liberal, and, being content with small profits, 'he soon found himself supported by a numerous and respectable set of friends, not one of whom ever quitted him.'

Jonah Bowyer was at the Rose, in Ludgate Street, in and about the year 1706, when he published the Lord Bishop of Oxford's 'Sermons preached before the Queen' at St. Paul's in May of that year; and it was either this Bowyer or William Bowyer—the two were not related—who established a bookselling department on the frozen Thames in 1716. William Johnston, who died at a very advanced age in 1804, was one of the most successful of Ludgate Hill booksellers, and his employées included George Robinson and Thomas Evans, each of whom became the founder of a very extensive business. George Conyers was at the Ring, Ludgate Hill, for some years during the last quarter of the seventeenth century, and prior to his removal to Little Britain. Conyers dealt chiefly in Grub Street compilations, which included cheap and handy guides to everything on earth, and it is likely that his shop was a literary or book-collecting resort. The most famous bibliopole who had a shop in Ludgate is perhaps William Hone, to whom the liberty of the press owes so much, and who removed here from his house at the corner of Ship Court, Old Bailey. Trübner and Co. left Ludgate Hill soon after they amalgamated with Kegan Paul, Trench and Co.

Copyright © D. J.McAdam· All Rights Reserved