[This is taken From P.H. Ditchfield's Books Fatal to Their Authors.]

Leland—Strutt—Cotgrave—Henry Wharton—Robert Heron—Collins—William Cole—Homeric victims—Joshua Barnes—An example of unrequited toil—Borgarutius—Pays.

We have still a list far too long of literary martyrs whose works have proved fatal to them, and yet whose names have not appeared in the foregoing chapters. These are they who have sacrificed their lives, their health and fortunes, for the sake of their works, and who had no sympathy with the saying of a professional hack writer, “Till fame appears to be worth more than money, I shall always prefer money to fame.” For the labours of their lives they have received no compensation at all. Health, eyesight, and even life itself have been devoted to the service of mankind, who have shown themselves somewhat ungrateful recipients of their bounty.

Some of the more illustrious scholars indeed enjoy a posthumous fame,-- their names are still honoured; their works are still read and studied by the learned,--but what countless multitudes are those who have sacrificed their all, and yet slumber in nameless graves, the ocean of oblivion having long since washed out the footprints they hoped to leave upon the shifting sands of Time! Of these we have no record; let us enumerate a few of the scholars of an elder age whose books proved fatal to them, and whose sorrows and early deaths were brought on by their devotion to literature.

What antiquary has not been grateful to Leland, the father of English archaeology! He possessed that ardent love for the records of the past which must inspire the heart and the pen of every true antiquary; that accurate learning and indefatigable spirit of research without which the historian, however zealous, must inevitably err; and that sturdy patriotism which led him to prefer the study of the past glories of his own to those of any other people or land. His Cygnea Cantio will live as long as the silvery Thames, whose glories he loved to sing, pursues its beauteous way through the loveliest vales of England. While his royal patron, Henry VIII., lived, all went well; after the death of that monarch his anxieties and troubles began. His pension became smaller, and at length ceased. No one seemed to appreciate his toil. He became melancholy and morose, and the effect of nightly vigils and years of toil began to tell upon his constitution. At length his mind gave way, ere yet the middle stage of life was passed; and although many other famous antiquaries have followed his steps and profited by his writings and his example, English scholars will ever mourn the sad and painful end of unhappy Leland.

Another antiquary was scarcely more fortunate. Strutt, the author of English Sports and Pastimes, whose works every student of the manners and customs of our forefathers has read and delighted in, passed his days in poverty and obscurity, and often received no recompense for the works which are now so valuable. At least he had his early wish gratified,--“I will strive to leave my name behind me in the world, if not in the splendour that some have, at least with some marks of assiduity and study which shall never be wanting in me.”

Randle Cotgrave, the compiler of one of the most valuable dictionaries of early English words, lost his eyesight through laboriously studying ancient MSS. in his pursuit of knowledge. The sixteen volumes of MS. preserved in the Lambeth Library of English literature killed their author, Henry Wharton, before he reached his thirtieth year. By the indiscreet exertion of his mind, in protracted and incessant literary labours, poor Robert Heron destroyed his health, and after years of toil spent in producing volumes so numerous and so varied as to stagger one to contemplate, ended his days in Newgate. In his pathetic appeal for help to the Literary Fund, wherein he enumerates the labours of his life, he wrote, “I shudder at the thought of perishing in gaol.” And yet that was the fate of Heron, a man of amazing industry and vast learning and ability, a martyr to literature.

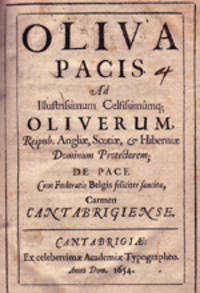

He has unhappily many companions, whose names appear upon that mournful roll of luckless authors. There is the unfortunate poet Collins, who was driven insane by the disappointment attending his unremunerative toil, and the want of public appreciation of his verses. William Cole, the writer of fifty volumes in MS. of the Athenae Cantabrigienses, founded upon the same principle as the Athenae Oxonienses of Anthony Wood, lived to see his hopes of fame die, and yet to feel that he could not abandon his self-imposed task, as that would be death to him. Homer, too, has had some victims; and if he has suffered from translation, he has revenged himself on his translators. A learned writer, Joshua Barnes, Professor of Greek at Cambridge, devoted his whole energy to the task, and ended his days in abject poverty, disgusted with the scanty rewards his great industry and scholarship had attained. A more humble translator, a chemist of Reading, published an English version of the Iliad. The fascination of the work drew him away from his business, and caused his ruin. A clergyman died a few years ago who had devoted many years to a learned Biblical Commentary; it was the work of his life, and contained the results of much original research. After his death his effects were sold, and with them the precious MS., the result of so many hours of patient labour; this MS. realised three shillings and sixpence!

Fatal indeed have their works and love of literature proved to be to many a luckless author. No wonder that many of them have vowed, like Borgarutius, that they would write no more nor spend their life-blood for the sake of so fickle a mistress, or so thankless a public. This author was so troubled by the difficulties he encountered in printing his book on Anatomy, that he made the rash vow that he would never publish anything more; but, like many other authors, he broke his word. Poets are especially liable to this change of intention, as La Fontaine observes:--

“O! combien l’homme est inconstant, divers,

Foible, leger, tenant mal sa parole,

J’avois jure, meme en assez beaux vers,

De renouncer a tout Conte frivole.

Depuis deux jours j’ai fait cette promesse

Puis fiez-vous a Rimeur qui repond

D’un seul moment. Dieu ne fit la sagesse

Pour les cerveaux qui hantent les neuf Soeurs.”

In these days of omnivorous readers, the position of authors has decidedly improved. We no longer see the half-starved poets bartering their sonnets for a meal; learned scholars pining in Newgate; nor is “half the pay of a scavenger” [Footnote: A remark of Granger—vide Calamities of Authors, p. 85.] considered sufficient remuneration for recondite treatises. It has been the fashion of authors of all ages to complain bitterly of their own times. Bayle calls it an epidemical disease in the republic of letters, and poets seem especially liable to this complaint. Usually those who are most favoured by fortune bewail their fate with vehemence; while poor and unfortunate authors write cheerfully. To judge from his writings one would imagine that Balzac pined in poverty; whereas he was living in the greatest luxury, surrounded by friends who enjoyed his hospitality. Oftentimes this language of complaint is a sign of the ingratitude of authors towards their age, rather than a testimony of the ingratitude of the age towards authors. Thus did the French poet Pays abuse his fate: “I was born under a certain star, whose malignity cannot be overcome; and I am so persuaded of the power of this malevolent star, that I accuse it of all misfortunes, and I never lay the fault upon anybody.” He has courted Fortune in vain. She will have nought to do with his addresses, and it would be just as foolish to afflict oneself because of an eclipse of the sun or moon, as to be grieved on account of the changes which Fortune is pleased to cause. Many other writers speak in the same fretful strain. There is now work in the vast field of literature for all who have the taste, ability, and requisite knowledge; and few authors now find their books fatal to them—except perhaps to their reputation, when they deserve the critics’ censures. The writers of novels certainly have no cause to complain of the unkindness of the public and their lack of appreciation, and the vast numbers of novels which are produced every year would have certainly astonished the readers of thirty or forty years ago.

For the production of learned works which appeal only to a few scholars, modern authors have the aid of the Clarendon Press and other institutions which are subsidised by the Universities for the purpose of publishing such works. But in spite of all the advantages which modern authors enjoy, the great demand for literature of all kinds, the justice and fair dealing of publishers, the adequate remuneration which is usually received for their works, the favourable laws of copyright—in spite of all these and other advantages, the lamentable woes of authors have not yet ceased. The leaders of literature can hold their own, and prosper well; but the men who stand in the second, third, or fourth rank in the great literary army, have still cause to bewail the unkindness of the blind goddess who contrives to see sufficiently to avoid all their approaches to her.

For these brave, but often disheartened, toilers that noble institution, the Royal Literary Fund, has accomplished great things. During a period of more than a century it has carried on its beneficent work, relieving poor struggling authors when poverty and sickness have laid them low; and it has proved itself to be a “nursing mother” to the wives and children of literary martyrs who have been quite unable to provide for the wants of their distressed families. We have already alluded to the foundation of the Royal Literary Fund, which arose from the feelings of pity and regret excited by the death of Floyer Sydenham in a debtors’ prison. It is unnecessary to record its history, its noble career of unobtrusive usefulness in saving from ruin and ministering consolation to those unhappy authors who have been wounded in the world’s warfare, and who, but for the Literary Fund, would have been left to perish on the hard battlefield of life. Since its foundation £115,677 has been spent in 4,332 grants to distressed authors. All book-lovers will, we doubt not, seek to help forward this noble work, and will endeavour to prevent, as far as possible, any more distressing cases of literary martyrdom, which have so often stained the sad pages of our literary history.

In order to diminish the woes of authors and to help the maimed and wounded warriors in the service of Literature, we should like to rear a large Literary College, where those who have borne the burden and heat of the day may rest secure from all anxieties and worldly worries when the evening shadows of life fall around. Possibly the authorities of the Royal Literary Fund might be able to accomplish this grand enterprise. In imagination we seem to see a noble building like an Oxford College, or the Charterhouse, wherein the veterans of Literature can live and work and end their days, free from the perplexities and difficulties to which poverty and distress have so long accustomed them. There is a Library, rich with the choicest works. The Historian, the Poet, the Divine, the Scientist, can here pursue their studies, and breathe forth inspired thoughts which the res angusta domi have so long stifled. In society congenial to their tastes, far from “the madding crowd’s ignoble strife,” they may succeed in accomplishing their life’s work, and their happiness would be the happiness of the community.

If this be but a dream, it is a pleasant one. But if all book-lovers would unite for the purpose of founding such a Literary College, it might be possible for the dream to be realized. Then the woes of future generations of authors might be effectually diminished, and Fatal Books have less unhappy victims.

Copyright © D. J.McAdam· All Rights Reserved