[This is taken from David N. Carvalho's Forty Centuries of Ink, originally published in 1904.]

THE GRAVING TOOL PRECEDES THE PEN—CLASSIFICATION UNDER TWO HEADS, ONE WHICH SCRATCHED AND THE OTHER WHICH USED AN INK—THE STYLUS AND THE MATERIALS OF WHICH IT WAS COMPOSED—POETICALLY DESCRIBED—COMMENTS BY NOEL HUMPHREYS—RECAPITULATION OF VARIOUS DEVICES BY KNIGHT—BIBLICAL REFERENCES—ENGRAVED STONES AND OTHER MATERIALS THE EARLIEST KINDS OF RECORDS—WHEN THIN BRICKS WERE UTILIZED FOR INSCRIPTION PURPOSES— ETHODS EMPLOYED BY THE CHINESE—HILPRECHT’S DISCOVERIES—THE DIAMOND AS A SCRATCHING INSTRUMENT—HISTORICAL INCIDENT WRITTEN WITH ONE—BIBLICAL MENTION ABOUT THE DIAMOND—WHEN IT BECAME POSSIBLE TO INTERPRET CHARACTER VALUES OF ANCIENT HIEROGLYPHICS—DISCOVERY OF THE ROSETTA STONE AND A DESCRIPTION OF IT—SOME OBSERVATIONS ABOUT CHAMPOLLION AND DR. YOUNG WHO DECIPHERED IT—ITS CAPTURE BY THE ENGLISH AND PRESERVATION IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM—EMPLOYMENT OF THE REED PEN AND PENCIL-BRUSH—THE BRUSH PRECEDED THE REED PEN—THE PLACES WHERE THE REEDS GREW—COMMENTS BY VARIOUS WRITERS—METHOD OF FORMING THE REED INTO A PEN—CONTINUED EMPLOYMENT OF THEM IN THE FAR EAST—THE BRUSH STILL IN USE IN CHINA AND JAPAN—EARLIEST EXAMPLES OF REED PEN WRITING—WHEN THE QUILL WAS SUBSTITUTED FOR THE REED—REED PENS FOUND IN THE RUINS OF HERCULANEUM—ANECDOTE BY THE ABBE, HUE.

The instruments of antiquity employed in the art of writing belong to two of the most distant epochs.

In the first period, inscriptions were engraved, carved or impressed with sharp instruments, and of patterns characteristic of a graving tool, chisel or other form which could be adapted to particular substances like stone, leaves, metal or ivory plates, wax or clay tablets, cylinders and prisms.

The ancient Assyrians even used knives or stamps for impressing their cuneiform writing upon cylinders or prisms of soft clay which were often glazed by subsequent bakings in kilns.

The other period was that in which written characters were made with liquids or paints of any kind or color. The liquids (inks) were used in connection with a pen manufactured from a reed (calamus), while the paints were “painted” on the various substances with a brush. The writing executed with both of these instruments was on materials like the bark of trees, cloth, skins, papyrus, vellum, etc.

The ancient as well as modern pens, though of many sorts and kinds, are to be classified under two general heads, those which scratch and those which use an ink.

There is no authority to dispute the generally conceded fact that the “scratching” instrument was the first one used. Its most popular form seems to have been the stylus or bodkin, which was made of a variety of materials, such as iron, ivory, bone, minerals or any other hard substance, which could be sufficiently sharpened at one end to indent the various materials employed in connection with its use. The other end was flattened for erasing marks made on wax and smoothing it. From it the Italian stilletto took its origin.

The stylus is best described in the following lines:

“My head is flat and smooth, but sharp my foot,

And by man’s hand to different uses put;

For what my foot performs with art and care,

My head makes void, such opposites they are.”

Relative to the employment of marking instruments which belong to the most venerable antiquity, Noel Humphreys observes:

“Before the growth of wealth and luxury had taught nations to raise magnificent temples and stately palaces, whose walls the hieroglyphic sculptor covered with records of the pomp and pride of princes, more purely national memorials had found their place upon the native rock, the most convenient surfaces of which were smoothed for this purpose. Where no such rock existed in the situation required, a massive stone was raised by artificial means and the record, whether referring to a victory, a new boundary, or any other event of national interest was engraved upon it. Such memorials have been described by Hebrew writers as aumad or ammod, literally, the lips of the people, or, the words of the people, but actually meaning a pillar. Records in this form and the early name they bore account for the strange legends of mediaeval times referring to speaking stones—a name by which such monuments were probably still called long after time had effaced the speaking record, and the original purport of the defaced stone was forgotten. In semi-barbarous epochs, like the era which followed the partial extinction of Roman civilization, popular curiosity and superstition combined would seek to give a meaning to the name of such ‘speaking stones,’ and as an example of the legends which thus arose, the itinerarium cambriae of Geraldus may be cited, in which a stone is mentioned at St. David’s as the ‘speaking stone’ (lech lavar) which was said to call out when a dead body was placed upon it. The most remarkable rock inscriptions still remaining are those of Assyria and Persia, but many national tablets of more recent date are still in existence. For the execution of such records and those of the palaces of Egypt and Assyria, some kind of steel point must have been used, as no softer substance would have served to engrave them in granitic and basaltic slabs with the sharpness they still exhibit, which proves that the art of hardening steel, long thought a comparatively modern invention, was known to the ancient people of Asia and Africa.”

A list of the various devices of different countries, by which characters could be legibly portrayed with a scratching implement, is best recapitulated by Mr. Knight, who presents them in the following order:

“The tabula or wooden board smeared with wax, upon which a letter was written by a stylus.

“The Athenian scratched his vote upon a shell as did the lout when he voted to ostracize Aristides.

“The records of Ninevah were inscribed upon tablets of clay, which were then baked.

“The laws of Rome were engraved on brass and laid up in the Capitol.

“The decalogue was graven upon the tables of stone.

“The Egyptians used papyrus and granite.

“The Burmese, tablets of ivory and leaves.

“Pliny mentions sheets of lead, books of linen, and waxed tablets of wood.

“The Hebrews used linen and skins.

“The Persians, Mexicans, and North American Indians used skins.

“The Greeks, prepared skins called membrana.

“The people of Pergamus, parchment and vellum.

“The Hindoos, palm-leaves.”

The written deeds of biblical time were kept in various styles of pottery (Jeremiah xxxii. 14). Handwriting on tiles was common in Egypt, Assyria and Palestine (Ezekiel iv. I). Such handwritings were on tablets of terra-cotta or common baked clay bricks. One of the kind was fashioned by inscribing directly with a “stylus” on the clay, before baking. Another, were “moulds” made from older inscriptions or duplicates from the first kind.

The Hebrew term sepher, translated into English means a “book,” and some authorities claim it is derived from the same root as the Greek <gr kefas>, a stone, which would seem to point to engraved stones as the earliest kinds of records. Indeed nearly all the passages in the Five Books of Moses, in which writing is mentioned, refer to records of this kind, or to tablets of lead or wood, occasionally described as coated with wax.

Long before the use of papyrus, or any like substance was known as a material for writing on, thin bricks were frequently utilized for such purposes. The Chinese wrote on slips of bamboo which had been previously scraped to be afterwards submitted to intense heat which so hardened them, that a graver would cut lines with the same facility, as could be accomplished on soft metal like lead. These bamboo tablets were joined together by means of cords made of bark and when folded formed a “book.” Different nations adopted other modes in their preparation of surfaces to engrave on. Many original specimens have come down to us which present definite evidence of the variety of materials and methods employed in their manufacture.

Hilprecht, “Explorations in Bible Lands,” 1903, mentions many discoveries of such specimens. He says that more than four thousand clay tablets were discovered during the excavations of 1889 and 1900.

These relics call attention only to a very few discoveries of this character. There were other explorers who preceded Hilprecht in this direction, and who with him have thus secured tangible evidence which fully confirms all that has been said about the employment of the most ancient of writing instruments, the “stylus.”

The diamond is also to be classified under the head of “scratching implements” and many historical incidents are recorded of its use. One of the most interesting relates to Sir Walter Raleigh and Queen Elizabeth and to be found in Scott’s “Kenilworth.” Sir Walter, using his diamond ring, wrote on a pane of glass in her summer-house at Greenwich:

“Fain would I climb, but that I fear to fall.”

The maiden Queen adding the words:

“If thy mind fail thee, do not climb at all.”

Biblical mention of the diamond, employed as a pen, is found in Jeremiah xvii. 1.

“The sin of Judah is written with a pen of iron, and with the point of a diamond.”

It has not always been possible to decipher and interpret the character values of the most ancient hieroglyphics or picture writings inscribed on bricks, stone and metal slabs, and the Egyptian monuments. The means to do so were furnished as the result of a very fortunate accident or “find.”

A French artillery officer in 1799 while excavating the foundations for a fortification near the Rosetta mouth of the Nile, found a curious black tablet of stone. On it were engraved three inscriptions, each of different characters and dialects.

The first of the three inscriptions was in hieroglyphic, then unreadable; the second in demotic or shorter script, also unknown, and the third in a living language pertaining to the time of Ptolemy Epiphanes, who reigned about 200 B. C.

This relic of antiquity is called the Rosetta stone.

Jean Francois Champollion, who with Dr. Thomas Young studied the intricacies of these writings, first established the fact that the three inscriptions on this stone were translations of each other. Dr. Young’s investigations caused him to study the language included in the second inscription, and made his deductions, it is said, “by dint of thousands of scientific guesses, all but a few of which were eliminated by tests which he invented and applied; he at last discovered and put together the set of fundamental principles that govern the ancient writings.”

Champollion, however, began at the bottom and having successfully translated the LIVING language, established a “key” or alphabet. Hence it became possible, although requiring some years, to solve the mystery of writings of 4000 or more years old.

Champollion pursued his discoveries so thoroughly in this direction as to be able to complete in 1829 an Egyptian vocabulary and grammar.

The Rosetta stone after remaining in the possession of the French for many years was captured by the English on the defeat of the French forces in Egypt and is now in the British museum.

As writing with liquid colors on papyrus or analogous materials which could be used in the form of rolls, gradually came into vogue, the calamus or reed pen, pencil brush (hair pencil), or the juncas, a pen formed from a kind of cane, were more or less employed.

The “calamus” followed the “brush,” just as phonographic writing which denotes arbitrary sounds or the language of symbols, came after the picture or ideographic writing.

The places where the calamus grew and the modes of preparing them are variously discussed by different ancient and modern writers. Some claim that the best reeds for pen purposes formerly grew near Memphis on the Nile, near Cnidus of Caria, in Asia Minor, and in Armenia. Those grown in Italy were estimated to have been of but poor quality. Chardin calls attention to a kind to be found, “in a large fen or tract of soggy land supplied with water by the river Helle, a place in Arabia formed by the united arms of the Euphrates and Tigris. They are cut in March, tied in bundles, laid six months in a manure heap, where they assume a beautiful color, mottled yellow and black.” Tournefort saw them growing in the neighborhood of Teflis in Georgia. Miller describes the cane as “growing no higher than a man, the stem three or four lines in thickness and solid from one knot to another, excepting the central white pith.” The incipient fermentation in the manure heap dries up the pith and hardens the cane. The pens were about the size of the largest swan’s quills. They were cut and slit like a quill pen but with much larger nibs.

In the far East the calamus is still used, the best being gathered in the month of March, near Aurac, on the Persian Gulf, and still prepared after the old method of immersing them for about six months in fermenting manure which coats them with a sort of dark varnish and the darker their color the more they are prized.

The “brush” also holds its career of usefulness, more especially in China and Japan.

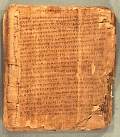

The earliest examples of reed pen writing are the ancient rolls of papyrus which have been found buried with the Egyptian dead. Some of these old relics of antiquity are claimed to have been prepared fully twenty centuries or more before the Christian era.

The “reed” pen for ink writing held almost undisputed sway until the sixth century after the Christian era, when the quill (penna) came into vogue.

Reed pens preserved in excellent condition were found in the ruins of Herculaneum.

“When he had finished, he dried the bamboo-pen on his hair, and replaced it behind his ear, saying, ‘Yak pose’ (That is well). ‘Temou chu’ (Rest in peace), we replied; and, after politely putting out our tongues, withdrew.” - Abbe Hue at Lhasa.

Copyright © D. J.McAdam· All Rights Reserved