Men naturally become reflective and somewhat introspective at midlife. It's a normal occurrence, but the results that follow from these introspections are sometimes dangerous, or at least dangerously ludicrous - hence the clichéd "midlife crisis," a generic term for a variety of antics middle-aged men occasionally engage in to somehow "prove" that we are still young (we're not), still virile (not something one should wish to prove, at least not in public), still sexy (again, not something one should try to prove).

Fortunately, I have been spared the danger of making such a spectacle of myself by my wife's insistence that my purchase of a sports car in my mid-thirties constituted my midlife crisis, and that I have therefore used up my normal allotment of such silliness. I don't completely agree with her assessment of this, but I also don't believe that I would get anywhere in attempting to argue the point, so there matters lie.

But I digress. This isn't about cars, or other frivolities. It's about hobbies. And the reason that I started this essay as I did is that, at midlife, and being of a reflective nature, I've come to realize that the many things that I thought were so important in life - promotions, job titles, being invited to the right parties - were nowhere nearly as important as my hobbies and pastimes, literally, "things to pass the time." If you're young - and that would be a very good time to read this, since you could benefit from my advice - you'll probably be tempted to disagree this assertion. If older, you'll already be nodding, without having to hear my arguments.

The truth is that most things in life that we tend to ascribe importance to are merely things that come and go. Your job title, unless you're something like the President of Harvard or the President of the United States or the President of General Motors, doesn't matter much to anyone but yourself and a few other coworkers. Some day, and sooner than you think, it won't matter to anyone at all. The promotions you receive at work will never stay in your mind the way the one promotion you didn't get will, and the same is true of party invitations. But hobbies are different.

A good hobby, pursued correctly, will never disappoint. And here I have to take a moment to explain what I mean by "pursued correctly." A hobby must be pursued, first and foremost, for pleasure, never gain. A good example of this presents itself every Spring in rural Vermont, where I used to reside. For a few weeks each year, when the daytime temperature is in the 40's and the nighttime temperature in the 20's, men and boys (and occasionally women and girls) get busy sugaring, turning the sap of maple trees into maple syrup. It's difficult, arduous work, and one wife calculated that her husband, after he had sold his batch of syrup, would have made an hourly wage from his work that would be about one-sixth of $6.25 per hour. But of course, he would not dream of not sugaring next year. He's not doing it for the money - he's doing it for the pleasure. For him, sugaring is a hobby, and if there's anything to show for his labors at the end of it, so much the better.

When I was young, a lot of hobby books used to have the phrase "For Pleasure and Profit" in the title, as in "How to Collect Picture Postcards for Pleasure and Profit." I think that's fine, as long as "pleasure" comes first. The tantalizing possibility of profit is a part of many hobbies. As a book collector, I often unearthed treasures that I purchased for as little as $5 that were worth in excess of $70, and such a find was always thrilling. But those finds remain on my shelves. I have no desire to see the books actually translated into cash. In the end, the thrill did not come from anything financial, but rather from the satisfaction that, on such occasions, there was the possibility that I knew something the "expert" dealer did not. Heady stuff indeed.

I raise this point only because some time ago I read a number of letters to the editor of the journal of the American Philatelic Society with each letter's author similarly complaining that the $10,000 stamp collection he'd spent ten years building turned out to be, when he sold it, worth only half that, or worse. What nonsense! Does the man who spends ten years building model ships (an attractive hobby) expect people to treasure his models as much as he does? No. He builds models for his own pleasure, and the money he spends on his hobby is money spent in pursuit of pleasure; nothing more, and nothing less.

There are persons who can spend $10,000 on a stamp collection (or book collection, or some other kind of collection) and see it sell for $20,000. This happens with just enough frequency for the possibility to be enticing to other collectors. It is not the norm. It is the convergence of a number of factors, and one of the big factors is simply good luck. It's very similar to buying a house in a neighborhood that, twelve years later, becomes exceptionally desirable. Complaining when your collection doesn't sell for twice what you paid for it is like complaining when your horse doesn't win the race at Saratoga - pointless and unsportsmanlike. If you want to increase the chances of making money, then be honest with yourself about the fact, and don't call yourself a hobbyist. Call yourself an investor. Once you've taken that step, ask yourself if you might not be a wiser investor by simply putting your money into a savings account.

Having gotten that out of the way, let's get back to rhapsodizing about the wonders of hobbies. As I started to say before, a good hobby will never disappoint. The 3-volume, slipcased Lord of the Rings set I bought at the Peekskill Library book sale for $10 back in 1987 has provided pleasure ever since - and how often can you say that about a $10 purchase? In point of fact, other than the Lord of the Rings trilogy, there's nothing tangible that I purchased in 1987 that I can now recall having bought, although I'm quite sure that I spent a good deal more than $10 that year. Methods of obtaining such innocent, wholesome pleasures as these should not be regarded lightly.

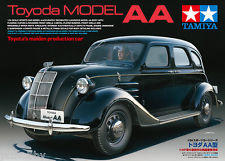

There's one more important point I should make about hobbies, which is that they can have a lifespan that is equivalent to that of the hobbyist himself. By way of comparison, that's hardly ever true of careers. Again using myself as an example, I started building scale models when I was a boy. I am now building models at what I hope is not too far past the middle of my life, and I am looking forward to building models for the remainder of my life. Hobbies don't care if you're young or old. If I no longer having the eyesight of a twenty-year-old, it's no matter - that's why they make things called Magnivisor's for hobbyists.

My suggestion, then, is that you take the advice of a man whose gray hair is no longer called premature, and that you find yourself a compatible hobby or two. It may be one that you revive from your youth, it may be something quite new. That's fine. Pursue it, enjoy it, and soon you'll find yourself developing a greater sense of context for what truly matters in life.

To ignite your thought processes, consider that Geoffrey Mott-Smith's The Handy Book of Hobbies: Make Your Spare Time Enjoyable and Profitable With A Hobby, published in 1949, is divided into the following sections:

Collecting Hobbies

Collecting Stamps

Collecting Coins and Medals

Collecting Buttons

Collecting Scientific Specimens

Collecting and Preserving Butterflies and Other Insects

Collecting and Preserving Plants

Collecting Minerals and Rocks

Collecting Shells

Collecting Autographs and Records

Model Making

Conjuring

Amateur Radio

Building Scale Models - model cars, model aircraft, etc.

Disclosure: We are independently owned and the opinions expressed here are our own. We do have advertisements with links to other sites on our pages, and may receive compensation when you click on one of those links and/or purchase something from one of those sites.

Copyright © D. J. McAdam· All Rights Reserved