[This is taken From P.H. Ditchfield's Books Fatal to Their Authors.]

Henry Cornelius Agrippa—Joseph Francis Borri—Urban Grandier—Dr. Dee—Edward Kelly—John Darrell.

Superstition is a deformed monster who dies hard; and like Loki of the Sagas when the snake dropped poison on his forehead, his writhings shook the world and caused earthquakes. Now its power is well-nigh dead. “Superstition! that horrible incubus which dwelt in darkness, shunning the light, with all its racks and poison-chalices, and foul sleeping-draughts, is passing away without return.” [Footnote: Carlyle.] But society was once leavened with it. Alchemy, astrology, and magic were a fashionable cult, and so long as its professors pleased their patrons, proclaimed “smooth things and prophesied deceits,” all went well with them; but it is an easy thing to offend fickle-minded folk, and when the philosopher’s stone and the secret of perpetual youth after much research were not producible, the cry of “impostor” was readily raised, and the trade of magic had its uncertainties, as well as its charms.

Our first author who suffered as an astrologer, though it is extremely doubtful whether he was ever guilty of the charges brought against him, was Henry Cornelius Agrippa, who was born at Cologne in 1486, a man of noble birth and learned in Medicine, Law, and Theology. His supposed devotion to necromancy and his adventurous career have made his story a favorite one for romance-writers. We find him in early life fighting in the Italian war under the Emperor Maximilian, whose private secretary he was. The honor of knighthood conferred upon him did not satisfy his ambition, and he betook himself to the fields of learning. At the request of Margaret of Austria, he wrote a treatise on the Excellence of Wisdom, which he had not the courage to publish, fearing to arouse the hostility of the theologians of the day, as his views were strongly opposed to the scholasticism of the monks. He lived the roving life of a mediaeval scholar, now in London illustrating the Epistles of St. Paul, now at Cologne or Pavia or Turin lecturing on Divinity, and at another time at Metz, where he resided some time and took part in the government of the city. There, in 1521, he was bereaved of his beautiful and noble wife.

There too we read of his charitable act of saving from death a poor woman who was accused of witchcraft. Then he became involved in controversy, combating the idea that St. Anne, the mother of the Blessed Virgin, had three husbands, and in consequence of the hostility raised by his opinions he was compelled to leave the city. The people used to avoid him, as if he carried about with him some dread infection, and fled from him whenever he appeared in the streets. At length we see him established at Lyons as physician to the Queen Mother, the Princess Louise of Savoy, and enjoying a pension from Francis I. This lady seems to have been of a superstitious turn of mind, and requested the learned Agrippa, whose fame for astrology had doubtless reached her, to consult the stars concerning the destinies of France. This Agrippa refused, and complained of being employed in such follies. His refusal aroused the ire of the Queen; her courtiers eagerly took up the cry, and “conjurer,” “necromancer,” etc., were the complimentary terms which were freely applied to the former favorite. Agrippa fled to the court of Margaret of Austria, the governor of the Netherlands under Charles V., and was appointed the Emperor’s historiographer. He wrote a history of the reign of that monarch, and during the life of Margaret he continued his prosperous career, and at her death he delivered an eloquent funeral oration.

But troubles were in store for the illustrious author. In 1530 he published a work, De Incertitudine et Vanitate Scientiarum et Artium, atque Excellentia Verbi Dei Dedamatio (Antwerp). His severe satire upon scholasticism and its professors roused the anger of those whom with scathing words he castigated. The Professors of the University of Louvain declared that they detected forty-three errors in the book; and Agrippa was forced to defend himself against their attacks in a little book published at Leyden, entitled Apologia pro defencione Declamationis de Vanitate Scientiarum contra Theologistes Lovanienses. In spite of such powerful friends as the Papal Legate, Cardinal Campeggio, and Cardinal de la Marck, Prince Bishop of Liege, Agrippa was vilified by his opponents, and imprisoned at Brussels in 1531. The fury against his book continued to rage, and its author declares in his Epistles: “When I brought out my book for the purpose of exciting sluggish minds to the study of sound learning, and to provide some new arguments for these monks to discuss in their assemblies, they repaid this kindness by rousing common hostility against me; and now by suggestions, from their pulpits, in public meetings, before mixed multitudes, with great clamorings they declaim against me; they rage with passion, and there is no impiety, no heresy, no disgrace which they do not charge me with, with wonderful gesticulations—namely, with clapping of fingers, with hands outstretched and then suddenly drawn back, with gnashing of teeth, by raging, by spitting, by scratching their heads, by gnawing their nails, by stamping with their feet, they rage like madmen, and omit no kind of lunatic behavior by means of which they may arouse the hatred and anger of both prince and people against me.”

The book was examined by the Inquisition and placed by the Council of Trent on the list of prohibited works, amongst the heretical books of the first class. Erasmus, however, spoke very highly of it, and declared it to be “the work of a man of sparkling intellect, of varied reading and good memory, who always blames bad things, and praises the good.” Schelhorn declares that the book is remarkable for the brilliant learning displayed in it, and for the very weighty testimony which it bears against the errors and faults of the time.

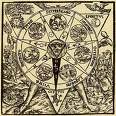

Our author was released from his prison at Brussels, and wrote another book, De occulta Philosophia (3 vols., Antwerp, 1533), which enabled his enemies to bring against him the charge of magic. Stories were told of the money which Agrippa paid at inns turning into pieces of horn and shell, and of the mysterious dog which ate and slept with him, which was indeed a demon in disguise and vanished at his death. They declared he had a wonderful wand, and a mirror which reflected the images of persons absent or dead.

The reputed wizard at length returned to France, where he was imprisoned on a charge of speaking evil of the Queen Mother, who had evidently not forgotten his refusal to consult the stars for her benefit. He was, however, soon released, and after his strange wandering life our author ended his labors in a hospital at Grenoble, where he died in 1535. In addition to the works we have mentioned, he wrote De Nobilitate et Proecellentia Faeminei Sexus (Antwerp, 1529), in order to flatter his patroness Margaret of Austria, and an early work, De Triplici Ratione Cognoscendi Deum (1515). The monkish epigram, unjust though it be, is perhaps worth recording:--

“Among the gods there is Momus who reviles all men; among the heroes there is Hercules who slays monsters; among the demons there is Pluto, the king of Erebus, who is in a rage with all the shades; among the philosophers there is Democritus who laughs at all things, Heraclitus who bewails all things, Pyrrhon who is ignorant of all things, Aristotle who thinks that he knows all things, Diogenes who despises all things. But this Agrippa spares none, despises all things, knows all things, is ignorant of all things, bewails all things, laughs at all things, rages against all things, reviles all things, being himself a philosopher, a demon, a hero, a god, everything.”

The impostor Joseph Francis Borri was a very different character. He was a famous chemist and charlatan, born at Milan in 1627, and educated by the Jesuits at Rome, being a student of medicine and chemistry. He lived a wild and depraved life, and was compelled to retire into a seminary. Then he suddenly changed his conduct, and pretended to be inspired by God, advocating in a book which he published certain strange notions with regard to the existence of the Trinity, and expressing certain ridiculous opinions, such as that the mother of God was a certain goddess, that the Holy Spirit became incarnate in the womb of Anna, and that not only Christ but the Virgin also are adored and contained in the Holy Eucharist.

In spite of the folly of his teaching he attracted many followers, and also the attention of the Inquisition. Perceiving his danger, he fled to Milan, and thence to a more safe retreat in Amsterdam and Hamburg. In his absence the Inquisition examined his book and passed its dread sentence upon its author, declaring that “Borri ought to be punished as a heretic for his errors, that he had incurred both the ‘general’ and ‘particular’ censures, that he was deprived of all honor and prerogative in the Church, of whose mercy he had proved himself unworthy, that he was expelled from her communion, and that his effigy should be handed over to the Cardinal Legate for the execution of the punishment he had deserved.” All his heretical writings were condemned to the flames, and all his goods confiscated. On the 3rd of January, 1661, Borri’s effigy and his books were burned by the public executioner, and Borri declared that he never felt so cold, when he knew that he was being burned by proxy. He then fled to a more secure asylum in Denmark. He imposed upon Frederick III., saying that he had found the philosopher’s stone. After the death of this credulous monarch Borri journeyed to Vienna, where he was delivered up to the representative of the Pope, and cast into prison. He was then sent to Rome, and condemned to perpetual imprisonment in the Castle of St. Angelo, where he died in 1685. His principal work was entitled La Chiave del gabineito del cavagliere G. F. Borri (The key of the cabinet of Borri). Certainly the Church showed him no mercy, but perhaps his hard fate was not entirely undeserved.

The tragic death of Urban Grandier shows how dangerous it was in the days of superstition to incur the displeasure of powerful men, and how easily the charge of necromancy could be used for the purpose of “removing” an obnoxious person. Grandier was cure of the Church of St. Peter at Loudun and canon of the Church of the Holy Cross. He was a pleasant companion, agreeable in conversation, and much admired by the fair sex. Indeed he wrote a book, Contra Caelibatum Clericorum, in which he strongly advocated the marriage of the clergy, and showed that he was not himself indifferent to the charms of the ladies. In an evil hour he wrote a little book entitled La cordonniere de Loudun, in which he attacked Richelieu, and aroused the undying hatred of the great Cardinal. Richelieu was at that time in the zenith of his power, and when offended he was not very scrupulous as to the means he employed to carry out his vengeance, as the fate of our author abundantly testifies.

In the town of Loudun was a famous convent of Ursuline nuns, and Grandier solicited the office of director of the nunnery, but happily he was prevented by circumstances from undertaking that duty. A short time afterwards the nuns were attacked with a curious and contagious frenzy, imagining themselves tormented by evil spirits, of whom the chief was Asmodeus. [Footnote: This was the demon mentioned in Tobit iii. 8, 17, who attacked Sarah, the daughter of Raguel, and killed her seven husbands. Rabbinical writers consider him as the chief of evil spirits, and recount his marvelous deeds. He is regarded as the fire of impure love.] They pretended that they were possessed by the demon, and accused the unhappy Grandier of casting the spells of witchcraft upon them. He indignantly refuted the calumny, and appealed to the Archbishop of Bordeaux, Charles de Sourdis. This wise prelate succeeded in calming the troubled minds of the nuns, and settled the affair.

In the meantime the vengeful eye of Richelieu was watching for an opportunity. He sent his emissary, Councilor Laubardemont, to Loudun, who renewed the accusation against Grandier. The amiable cleric, who had led a pious and regular life, was declared guilty of adultery, sacrilege, magic, witchcraft, demoniacal possession, and condemned to be burned alive after receiving an application of the torture. In the market-place of Loudun in 1643 this terrible sentence was carried into execution, and together with his book, Contra Caelibatum Clericorum, poor Grandier was committed to the flames. When he ascended his funeral pile, a fly was observed to buzz around his head. A monk who was standing near declared that, as Beelzebub was the god of flies, the devil was present with Grandier in his dying hour and wished to bear away his soul to the infernal regions. An account of this strange and tragic history was published by Aubin in his Histoire des diables de Loudun, ou cruels effets de la vengeance de Richelieu (Amsterdam, 1693).

Our own country has produced a noted alchemist and astrologer, Dr. Dee, whose fame extended to many lands. He was a very learned man and prolific writer, and obtained the office of warden of the collegiate church of Manchester through the favor of Queen Elizabeth, who was a firm believer in his astrological powers. His age was the age of witchcraft, and in no county was the belief in the magic power of the “evil eye” more prevalent than in Lancashire. Dr. Dee, however, disclaimed all dealings with “the black art” in his petition to the great “Solomon of the North,” James I., which was couched in these words: “It has been affirmed that your majesty’s suppliant was the conjurer belonging to the most honorable privy council of your majesty’s predecessor, of famous memory, Queen Elizabeth; and that he is, or hath been, a caller or invocator of devils, or damned spirits; these slanders, which have tended to his utter undoing, can no longer be endured; and if on trial he is found guilty of the offence imputed to him, he offers himself willingly to the punishment of death; yea, either to be stoned to death, or to be buried quick, or to be burned unmercifully.”

In spite of his assertions to the contrary, the learned doctor must have had an intimate acquaintance with “the black art,” and was the companion and friend of Edward Kelly, a notorious necromancer, who for his follies had his ears cut off at Lancaster. This Kelly used to exhume and consult the dead; in the darkness of night he and his companions entered churchyards, dug up the bodies of men recently buried, and caused them to utter predictions concerning the fate of the living. Dr. Dee’s friendship with Kelly was certainly suspicious. On the coronation of Queen Elizabeth, he foretold the future by consulting the stars. When a waxen image of the queen was found in Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields, which was a sure sign that some one was endeavoring to cast spells upon her majesty, Dr. Dee pretended that he was able to defeat the designs of such evil-disposed persons, and prevent his royal mistress feeling any of the pains which might be inflicted on her effigy. In addition his books, of which there were many, witness against him. These were collected by Casaubon, who published in London in 1659 a resume of the learned doctor’s works.

Manchester was made too hot, even for the alchemist, through the opposition of his clerical brethren, and he was compelled to resign his office of warden of the college. Then, accompanied by Kelly, he wandered abroad, and was received as an honored guest at the courts of many sovereigns. The Emperor Rodolphe, Stephen, King of Poland, and other royal personages welcomed the renowned astrologers, who could read the stars, had discovered the elixir of life, which rendered men immortal, the philosopher’s stone in the form of a powder which changed the bottom of a warming-pan into pure silver, simply by warming it at the fire, and made the precious metals so plentiful that children played at quoits with golden rings. No wonder they were so welcome! They were acquainted with the Rosicrucian philosophy, could hold correspondence with the spirits of the elements, imprison a spirit in a mirror, ring, or stone, and compel it to answer questions. Dr. Dee’s mirror, which worked such wonders, and was found in his study at his death in 1608, is now in the British Museum. In spite of all these marvels, the favor which the great man for a time enjoyed was fleet and transient. He fell into poverty and died in great misery, his downfall being brought about partly by his works but mainly by his practices.

Associated with Lancashire demonology is the name of John Darrell, a cleric, afterwards preacher at St. Mary’s, Nottingham, who published a narrative of the strange and grievous vexation of the devil of seven persons in Lancashire. This remarkable case occurred at Clayworth in the parish of Leigh, in the family of one Nicholas Starkie, whose house was turned into a perfect bedlam. It is vain to follow the account of the vagaries of the possessed, the howlings and barkings, the scratchings of holes for the familiars to get to them, the charms and magic circles of the impostor and exorcist Hartley, and the godly ministrations of the accomplished author, who with two other preachers overcame the evil spirits.

Unfortunately for him, Harsnett, Bishop of Chichester, and afterwards Archbishop of York, doubted the marvelous powers of the pious author, Dr. Darrell, and had the audacity to suggest that he made a trade of casting out devils, and even went so far as to declare that Darrell and the possessed had arranged the matter between them, and that Darrell had instructed them how they were to act in order to appear possessed. The author was subsequently condemned as an impostor by the Queen’s commissioners, deposed from his ministry, and condemned to a long term of imprisonment with further punishment to follow. The base conduct and pretences of Darrell and others obliged the clergy to enact the following canon (No. 73): “That no minister or ministers, without license and direction of the bishop, under his hand and seal obtained, attempt, upon any pretence whatsoever, either of possession or obsession, by fasting and prayer, to cast ‘out any devil or devils, under pain of the imputation of imposture, or cozenage, and deposition from the ministry.” This penalty at the present day not many of the clergy are in danger of incurring.

Copyright © D. J.McAdam· All Rights Reserved