[This is taken from David N. Carvalho's Forty Centuries of Ink, originally published in 1904.]

FROM WHENCE COMES THE NAME PAPER—FIRST CENTURY COMMENT ABOUT IT—KNIGHT’S COMMENTS MORE THAN 1,800 YEARS LATER—PAPYRUS AN EGYPTIAN REED—NAMES BESTOWED BY ANCIENT WRITERS—THE SAME NAMES AS EMPLOYED IN MODERN TIMES—LEAVES OF PLANTS PRECEDED THE INVENTION OF PAPYRUS—WHEN IT WAS THAT ROLLED RECORDS CAME INTO VOGUE—VARRO’S ESTIMATION AS TO THE ORIGINAL USE OF PAPYRUS NOT CORRECT—REAL FACTS RESPECTING THE INTRODUCTION OF PAPYRUS BEYOND THE LIMITS OF EGYPT—CHARACTER OF MATERIALS EMPLOYED BY THE GREEKS BEFORE THAT EPOCH—EMPLOYMENT OF IT FOR LITERARY PURPOSES—ADOPTION OF PARCHMENT AND VELLUM—PAPYRUS MSS. EMPLOYED IN THE FORM OF ROLLS AND THE REASON FOR SAME—ANCIENT MANUFACTURE OF PAPYRUS IN EGYPT—SOME OF THE NAMES USED TO DESIGNATE DIFFERENT KINDS—PLINY’S DESCRIPTION OF THE MANUFACTURE OF PAPYRUS AND HIS MISINFORMATION ABOUT IT—WHERE IT FLOURISHED BEST—PAPYRUS AS KNOWN TO THE HEBREWS AND ITS BIBLICAL MENTION—MANUFACTURE OF PAPYRUS IN THE ANCIENT CITY OF MEMPHIS—CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PAPER EMPLOYED BY THE MEXICANS—MR. HARRIS’S DISCOVERY OF ANCIENT FRAGMENTS OF PAPYRUS—THE STORY ABOUT IT AS TOLD BY THE LONDON ATHENAEUM—DATES OF THE OLDEST KNOWN SPECIMENS OF GREEK PAPYRI—DATE OF THE FIRST DISCOVERY OF GREEK PAPYRI—USE OF OTHER PLIABLE MATERIALS WITH PAPYRUS—HOW THEY WERE PREPARED FOR WRITING PURPOSES—DOUBTS AS TO TIME THAT ROLLED RECORDS SUPERSEDED TABLET FORMS—SUGGESTIONS BY NOEL HUMPHREYS—VIEWS ENTERTAINED BY EARLIER WRITERS.

THE name paper is derived from papyrus, a reed grown in Egypt, whose stalk furnished for so many centuries the principal material for writing upon to the people of that country and those bordering on the Mediterranean Sea. In the first century of the Christian era the younger Pliny remarks:

“All the usages of civilized life depend in a remarkable degree upon the employment of paper. At all events, the remembrance of past events.”

A statement which has caused Mr. Knight to make the following comment:

“This observation, undoubtedly true 1,800 years ago, is much more remarkably so now; indeed, in considering that paper as we now understand it was entirely unknown to Europe in the time of Pliny, the expression of the great dependence upon what seems to us so fragile and inefficient a substitute for real paper appears strange.”

Mr. Knight also says that the Greek name papuros, mentioned by Theophrastus, a contemporary of Aristotle and Alexander, was probably the Egyptian name of the reed with a Greek termination. It was also called biblos by Homer and Herodotus, whence our term bible. The term volumen, a scroll, indicates the early form of a book of bark, papyrus, skin, or parchment, as the term liber (Latin, a book, or the inner bark of a tree) does the use of the bark itself. Hence also our terms library and librarian. “Book” is also derived from the Danish word bog, the bark of the beech.

Pliny quoting Varro, who preceded him some two centuries, asserts that before the invention of papyrus, the large leaves of certain plants were prepared so that they could be written upon. Hence originates our term “leaves” of a book which in the Latin form folium has also given us the modern term folio.

When, however, the reed pen and the pencil brush and their kindred substances denominated colored liquids or inks, came into vogue, some material on which characters could be inscribed and preserved in the shape of continuous rolls for record and other uses became necessary. The papyrus plant seems to have met every requirement. It is a noteworthy fact that all information which can be derived from any source, specifically calls attention to papyrus and sometimes the inner barks of trees as being coexistent with pen and ink.

Varro has been credited with many statements which in the light of investigation and discovery are proved to be incorrect. One of these is in effect that the use of papyrus was an incident pertaining to the expeditions of Alexander the Great. This assertion is not only contradicted by Pliny, the historian, who calls attention to “books of papyrus found in the tomb of Numa “ (Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, B. C. 716-672,) but even at this late day many monuments of ancient papyri are still extant and belonging to periods more than a thousand years before Alexander’s time.

The real facts in respect to this matter are, that the introduction of the use of papyrus to nations beyond the limits of Egypt was an event that did not take place until after the reign of the first Macedonian sovereign of Egypt, Ptolemy Lagus (B. C. 323) when, in return for Greek literature, Egypt gave back her papyrus. Before this epoch the Greeks had been in the habit of employing such materials as linen, wax, bark and leaves for ordinary writing purposes, while their public records were inscribed on stone, brass, lead or other metals.

Papyrus as then introduced into those western countries was the only substance for a long period employed for literary purposes.

Parchment and vellum, which were adopted there as writing materials about two centuries later, were too costly to be used so long as papyrus was within reach.

When the use of this ancient paper had become established in the countries bordering on the Mediterranean, all the MSS. assumed the form of rolls, being rolled on cylinders of wood, ivory, bronze, glass and other substances. Sometimes, the ends were decorated by various ornaments. As a rule only one side of the material was written upon. This was due largely to the fact of its brittle character which would cause it to break if rolled or bent the wrong way.

The ancient manufacture of papyrus for export was carried on in Egypt on an extensive scale and in the most systematic manner. A gradual improvement in quality was the result, some of the kinds being given well-known Roman names which are mentioned by contemporary writers. The kind employed by the Romans for ordinary use was designated Charta. More expensive qualities were known as “Augusta,” “Livinia,” “Hieratica,” etc., the latter being reserved for religious books. Some kinds were sold by weight and employed by the tradesmen for wrapping purposes, while the bark of the plant was manufactured into cord and rope.

The methods of the manufacture of papyrus as a writing material Pliny undertakes to describe at great length, and while he asserts many things from probable knowledge and the information at hand in his time, yet he is not always correct. He says that the reed stalks were cut into lengths and separated “by splitting the successive folds of the stalk with a fine metal point.”

Mr. Knight, who investigated this matter with care, is authority for the statement, that the papyrus stalk as seen under the microscope shows that it does not possess successive folds, but is a triangular stalk with a single envelope with a pith on the inside, which could only be divided into slices with a knife, either in stripes of a width permitted by the sides of the prism, or else shaved round and round, like the operation of cork making, and producing a long spiral shaving.

In the description which Pliny gives of the various homes of this plant in Egypt, he calls particular attention to its abundance in marshy places where the Nile overflows and stagnates: “It grows like a great bulrush from fibrous, reedy roots, and runs up in several triangular stalks to a considerable height.” They possessed large tufted heads, but only the stem was fit for making into paper. After the pellicles or thin coats were removed from the stalk, they were laid upon tables two or more over each other and glued together with the muddy and glutinous water of the Nile or with fine paste made of wheat flour; after being pressed and dried they were made smooth with a ruler and then rubbed over with a glass hemisphere. The size of the paper seldom exceeded two feet.

Papyrus was also known to the Hebrews.

The Prophet Isaiah (B. C. 752) refers to this plant when he says:

“The paper reeds by the brooks, and everything sown by the brooks, shall wither, be driven away and be no more.”

Which prediction seems to have been long ago fulfilled as the plant is now exceedingly rare.

The manufacture of Egyptian paper from papyrus it is said was quite an industry in the ancient city of Memphis more than six hundred years before the Christian era.

The Mexicans employed for writing a paper which somewhat resembled the Egyptian papyrus. It was prepared from the aloe, called by the natives Maguey which grows wild over the tablelands of Mexico. It could be easily colored and seemed to bind to ink very closely. It could be rolled up in scrolls just like the more ancient rolls of papyrus.

The following account of an interesting discovery of a fragment of one of the “Orations of Hyperides,” by Mr. Harris, the well-known Oriental scholar, is derived from the London Athenaeum:

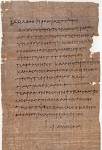

“In the winter of 1847 Mr. Harris was sitting in his boat, under the shade of the well-known sycamore, on the western bank of the Nile, at Thebes, ready to start for Nubia, when an Arab brought him a fragment of a papyrus roll, which he ventured to open sufficiently to ascertain that it was written in the Greek language, and which he bought before proceeding further on his journey. Upon his return to Alexandria, where circumstances were more favorable to the difficult operation of unrolling a fragile papyrus, he discovered that be possessed a fragment of the oration of Hyperides against Demosthenes, in the matter of Harpalus, and also a very small fragment of another oration, the whole written in extremely legible characters, and of a form or fashion which those learned in Greek MSS. consider to be of the time of the Ptolemies. With these interesting fragments of orations of an orator so celebrated is Hyperides, of whose works nothing, is extant but a few quotations in other Greek writers, he embarked for England. Upon his arrival there he submitted the precious relics to the inspection of the Council and members of the Royal Society of Literature, who were unanimous in their judgment as to the importance and genuineness of the MSS.; and Mr. Harris immediately set to work, and with his own hand made a lithographic facsimile of each piece. Of this performance a few copies were printed and distributed among the savants of Europe,--and Mr. Harris returned to Alexandria, whence he has made more than one journey to Thebes in the hope of discovering some other portion of the volume, of which he already had a part. In the same year (1847) another English gentleman, Mr. Joseph Arden, of London, bought at Thebes a papyrus, which he likewise brought to England. Induced by the success of Mr. Harris, Mr. Arden submitted his roll to the skilful and experienced hands of Mr. Hogarth; and upon the completion of the operation of unrolling, the MSS. was discovered to be the terminating portion of the very same volume of which Mr. Harris had bought a fragment of the former part in the very same year, and probably of the very same Arabs. No doubt now existed that the volume, when entire, consisted of a collection of, or a selection from, the orations of the celebrated Athenian orator, Hyperides.

“The portion of the volume which has fallen into the possession of Mr. Arden contains ‘fifteen continuous columns of the “Oration for Lycophron,” to which work three of Mr. Harris’s fragments appertained; and likewise the “Oration for Euxenippus,” which is quite complete and in beautiful preservation. Whether, as Mr. Babington observes in his preface to the work, any more scraps of the “Oration for Lycophron” or of the “Oration against Demosthenes” remain to be discovered, either in Thebes or elsewhere, may be doubtful, but is certainly worth the inquiry of learned travellers.’ The condition, however, of the fragments obtained by Mr. Harris but too significantly indicate the hopelessness of success. The scroll had evidently been more frequently rolled and unrolled in that particular part, namely, the speech of Hyperides in a matter of such peculiar interest as that involving the honor of the most celebrated orator of antiquity; it had been more read and had been more thumbed by ancient fingers than any other speech in the whole volume; and hence the terrible gap between Mr. Harris’s and Mr. Arden’s portions Those who are acquainted with the brittle, friable nature of a roll of papyrus in the dry climate of Thebes, after being buried two thousand years or more and then coming first into the hands of a ruthless Arab, who, perhaps, had rudely snatched it out of the sarcophagus of the mummied scribe, will well understand how dilapidations occur. It frequently happens that a single roll, or possibly an entire box, of such fragile treasures is found in the tomb of some ancient philologist or man of learning, and that the possession is immediately disputed by the company of Arabs who may have embarked on the venture. To settle the dispute, when there is not a scroll for each member of the company, an equitable division is made by dividing the papyrus and distributing the portions. Thus, in this volume of Hyperides, it seems that it has fallen into two pieces at the place where it had most usually been opened, and where, alas! it would have been most desirable to have kept it whole; and that the smaller fragments have been lost amid the dust and rubbish of the excavation, while the two extremities have been made distinct properties, which have been sold, as we have seen, to separate collectors. So, at all events, such matters are managed at Thebes.

“Mr. Harris mentions fragments of the ‘Iliad,’ which he had purchased of some of the Arab disturbers of the dead in the sacred cemeteries of Middle Egypt, most probably Saccara.”

The oldest known specimens of the Greek papyri and which were found in Egypt, have a range of one thousand years; that is, from the third century B. C. to the seventh century A. D.

The first discovery of Greek papyri was made at Herculaneum in 1752. Papyrus, however, in the most ancient, periods was not the only pliable material used to write on which could be rolled on cylinders. Linen or cloth, which had been first treated with substances which filled the interstices and characteristic of our oil-cloth, the inner bark of certain trees, or in fact any material which would receive ink and roll around a cylinder was in vogue. This form of manuscript was later termed by the Romans rolles, to roll round, or more commonly volvere, to roll over.

It is not certain, however, that this character of manuscript immediately superseded the tablet form of records inscribed on wood or metal. Noel Humphreys is one of several to suggest:

“The reference to the ‘pen of a ready writer,’ mentioned in the Psalms of David (B. C. 1086-1016) could scarcely be the sharp point, or stilus, by means of which characters were engraved upon wood or metal, but rather the calamus or juncas, used for writing with a dark fluid upon bark or linen. The word volume indeed occurs in Psalms xxxix., and these volumina or volumes must have been either rolls of leaves, or bark, or Egyptian papyrus.”

Some writers like Casley, Purcelli, Haygen, Calmet, and others, who also more or less discuss this subject, do not view it entirely the same.

Copyright © D. J. McAdam· All Rights Reserved