(This is taken from John D. Baldwin's Ancient America, originally published in 1871.)

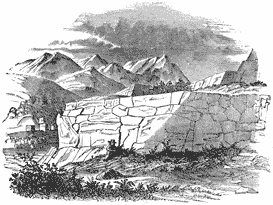

The ruins of Ancient Peru are found chiefly on the elevated table-lands of the Andes, between Quito and Lake Titicaca; but they can be traced five hundred miles farther south, to Chili, and throughout the region connecting these high plateaus with the Pacific coast. The great district to which they belong extends north and south about two thousand miles. When the marauding Spaniards arrived in the country, this whole region was the seat of a populous and prosperous empire, complete in its civil organization, supported by an efficient system of industry, and presenting a very notable development of some of the more important arts of civilized life. These ruins differ from those in Mexico and Central America. No inscriptions are found in Peru; there is no longer a “marvelous abundance of decorations;” nothing is seen like the monoliths of Copan or the bas-reliefs of Palenque. The method of building is different; the Peruvian temples were not high truncated pyramids, and the great edifices were not erected on pyramidal foundations. The Peruvian ruins show us remains of cities, temples, palaces, other edifices of various kinds, fortresses, aqueducts (one of them four hundred and fifty miles long), great roads (extending through the whole length of the empire), and terraces on the sides of mountains. For all these constructions the builders used cut stone laid in mortar or cement, and their work was done admirably, but it is every where seen that the masonry, although sometimes ornamented, was generally plain in style and always massive. The antiquities in this region have not been as much explored and described as those north of the isthmus, but their general character is known, and particular descriptions of some of them have been published.

THE SPANISH HUNT FOR PERU.

The Spanish conquest of Peru furnishes one of the most remarkable chapters in the history of audacious villainy. It was the work of successful buccaneers as unscrupulous as any crew of pirates that ever robbed and murdered on the ocean. After their settlements began on the islands and the Atlantic coast, rumors came to them of a wonderful country somewhere at a distance in the west. They knew nothing of another ocean between them and the Indies; the western side of the continent was a veiled land of mystery, but the rumors, constantly repeated, assured them that there was a country in that unknown region where gold was more abundant than iron among themselves. Their strongest passions were moved; greed for the precious metals and thirst for adventures.

Balboa was hunting for Peru when he discovered the Pacific, about 1511 A.D. He was guided across the isthmus by a young native chief, who told him of that ocean, saying it was the best way to the country where all the common household utensils were made of gold. At the Bay of Panama Balboa heard more of Peru, and went down the coast to find it, but did not go south much beyond the eighth degree of north latitude. In his company of adventurers at this time was Francisco Pizarro, by whom Peru was found, subjugated, robbed, and ruined, some fifteen or twenty years later. Balboa was superseded by Pedrarias, another greedy adventurer, whose jealousy arrested his operations and finally put him to death. The town of Panama was founded in 1519 by this Pedrarias, chiefly as a point on the Pacific from which he could seek and attack Peru. Under his direction, in 1522, the search was attempted by Pascual de Andagoya, but he failed to get down the coast beyond the limit of Balboa’s exploration. Meanwhile clearer and more abundant reports of the rich and marvelous nation to be found somewhere below that point were circulated among the Spaniards, and their eagerness to reach it became intense.

In 1524, three men could have been seen in Panama busily engaged preparing another expedition to go in search of the golden country. These were Francisco Pizarro, a bold and capable adventurer, who could neither read nor write; Diego de Almagro, an impulsive, passionate, reckless soldier of fortune, and Hernando de Luque, a Spanish ecclesiastic, Vicar of Panama, and a man well acquainted with the world and skilled in reading character, acting at this time, it is said, for another person who kept out of view. They had formed an alliance to discover and rob Peru. Luque would furnish most of the funds, and wait in Panama for the others to do the work. Pizarro would be commander-in-chief. The vessels used would necessarily be such as could be built at Panama, and, therefore, not very efficient.

Pizarro went down the coast, landing from time to time to explore and rob villages, until he reached about the fourth degree of north latitude, when he was obliged to return for supplies and repairs. It became necessary to reconstruct the contract and allow Pedrarias an interest in it. On the next voyage, one of the vessels went half a degree south of the equator, and encountered a vessel “like a European caravel,” which was, in fact, a Peruvian balsa, loaded with merchandise, vases, mirrors of burnished silver, and curious fabrics of cotton and woolen.

It became again indispensable to send back to Panama for supplies and repairs, and Pizarro was doomed to wait for them seven months on an island. He next visited Tumbez, in Peru, and went to the ninth degree of south latitude; but he was obliged to visit Spain to get necessary aid before he could attempt any thing more, and it was not until the year 1531 that the conquest of Peru was actually undertaken.

In 1531 Pizarro finally entered Tumbez with his buccaneers, and marched into the country, sending word to the Inca that he came to aid him against his enemies. There had been a civil war in the country, which had been divided by the great Inca, Huayna Capac, the conqueror of Quito, between his two sons, Huascar and Atahuallpa, and Huascar had been defeated and thrown into prison, and finally put to death. At a city called Caxamalca, Pizarro contrived, by means of the most atrocious treachery, to seize the Inca and massacre some ten thousand of the principal Peruvians, who came to his camp unarmed on a friendly visit. This threw the whole empire into confusion, and made the conquest easy. The Inca filled a room with gold as the price of his ransom; the Spaniards took the gold, broke their promise, and put him to death.

Disclosure: We are independently owned and the opinions expressed here are our own. We do have advertisements with links to other sites on our pages, and may receive compensation when you click on one of those links and/or purchase something from one of those sites.

Copyright © D. J. McAdam· All Rights Reserved