This is taken from John D. Baldwin's Ancient America, originally published in 1871.

The Mexican and Central American ruins make it certain that in ancient times an important civilization existed in that part of the continent, which must have begun at a remote period in the past. If they have any significance, this must be accepted as an ascertained fact. A large proportion of them had been forgotten in the forests, or become mythical and mysterious, long before the arrival of the Spaniards.

In 1520, three hundred and fifty years ago, the forest which so largely covers Yucatan, Guatemala, and Chiapa was growing as it grows now; yes, four hundred and fifty years ago, for it was there a century previous to this date, when, the Maya kingdom being broken up, one of its princes fled into this forest with a portion of his people, the Itzas, and settled at Lake Peten. It was the same then as now. How many additional centuries it had existed no one can tell. If its age could be told, it would still be necessary to consider that the ruins hidden in it are much older than the forest, and that the period of civilization they represent closed long before it was established.

In the ages previous to the beginning of this immense forest, the region it covers was the seat of a civilization which grew up to a high degree of development, flourished a long time, and finally declined, until its cities were deserted, and its cultivated fields left to the wild influences of nature. It may be safely assumed that both the forest-covered ruins and the forest itself are far older than the Aztec period; but who can tell how much older? Copan, first discovered and described three hundred years ago, was then as strange to the natives dwelling near it as the old Chaldean ruins are to the Arabs who wander over the wasted plains of Lower Mesopotamia. Native tradition had forgotten its history and become silent in regard to it. How long had ruined Copan been in this condition? No one can tell. Manifestly it was forgotten, left buried in the forest without recollection of its history, long before Montezuma’s people, the Aztecs, rose to power; and it is easily understood that this old city had an important history previous to that unknown time in the past when war, revolution, or some other agency of destruction put an end to its career and left it to become what it is now.

Moreover, these old ruins, in all cases, show us only the cities last occupied in the periods to which they belong. Doubtless others still older preceded them; and, besides, it can be seen that some of the ruined cities which can now be traced were several times renewed by reconstructions. We must consider, also, that building magnificent cities is not the first work of an original civilization. The development was necessarily gradual. Its first period was more or less rude. The art of building and ornamenting such edifices arose slowly. Many ages must have been required to develop such admirable skill in masonry and ornamentation. Therefore the period between the beginning of this mysterious development of civilized life and the first builders who used cut stone laid in mortar and cement, and covered their work with beautifully sculptured ornaments and inscriptions, must have been very long.

We have no measure of the time, no clew to the old dates, nothing whatever, beyond such considerations as I have stated, to warrant even a vague hypothesis. It can be seen clearly that the beginning of this old civilization was much older than the earliest great cities, and, also, that these were much more ancient than the time when any of the later built or reconstructed cities whose relics still exist, were left to decay. If we suppose Palenque to have been deserted some six hundred years previous to the Spanish Conquest, this date will carry us back only to the last days of its history as an inhabited city. Beyond it, in the distant past, is a vast period, in which the civilization represented by Palenque was developed, made capable of building such cities, and then carried on through the many ages during which cities became numerous, flourished, grew old, and gave place to others, until the long history of Palenque itself began.

Those who have sought to discredit what is told of the Aztec civilization and the empire of Montezuma have never failed to admit fully the significance of Copan, Palenque, and Mitla. One or two writers, pursuing the assumption that the barbarous tribes at the north and the old Mexicans were of the same race, and substantially the same people, have undertaken to give us the history of Montezuma’s empire “entirely rewritten,” and show that his people were “Mexican savages.” In their hands Montezuma is transformed into a barbarous Indian chief, and the city of Mexico becomes a rude Indian village, situated among the islands and lagoons of an everglade which afforded unusual facilities “for fishing and snaring birds.” One goes so far as to maintain this with considerable vehemence and amusing unconsciousness of absurdity. He is sure that Montezuma was nothing more than the principal chief of a parcel of wild Indian tribes, and that the Pueblos are wild Indians changed to their present condition by Spanish influence. There is something in this akin to lunacy.

But this topic will receive more attention in another place. I bring it to view here because those who maintain so strangely that the Aztecs were Indian savages, admit all that is claimed for the wonderful ruins at the south, and give them a very great antiquity. They maintain, however, that the civilization represented by these ruins was brought to this continent in remote pre-historic times by the people known as Phoenicians, and their method of finding the Phoenicians at Palenque, Copan, and every where else, is similar in character and value to that by which they transform the Aztec empire into a rude confederacy of wild Indians.

DISTINCT ERAS TRACED.

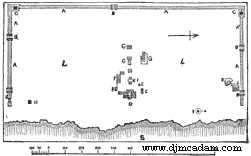

It is a point of no little interest that these old constructions belong to different periods in the past, and represent somewhat different phases of civilization. Uxmal, which is supposed to have been partly inhabited when the Spaniards arrived in the country, is plainly much more modern than Copan or Palenque. This is easily traced in the ruins. Its edifices were finished in a different style, and show fewer inscriptions. Round pillars, somewhat in the Doric style, are found at Uxmal, but none like the square, richly-carved pillars, bearing inscriptions, discovered in some of the other ruins. Copan and Palenque, and even Kabah, in Yucatan, may have been very old cities, if not already old ruins, when Uxmal was built. Accepting the reports of explorers as correct, there is evidence in the ruins that Quirigua is older than Copan, and that Copan is older than Palenque. The old monuments in Yucatan represent several distinct epochs in the ancient history of that peninsula. Some of them are kindred to those hidden in the great forest, and remind us more of Palenque than of Uxmal. Among those described, the most modern, or most of these, are in Yucatan; they belong to the time when the kingdom of the Mayas flourished. Many of the others belong to ages previous to the rise of this kingdom; and in ages still earlier, ages older than the great forest, there were other cities, doubtless, whose remains have perished utterly, or were long ago removed for use in the later constructions.

The evidence of repeated reconstructions in some of the cities before they were deserted has been pointed out by explorers. I have quoted what Charnay says of it in his description of Mitla. At Palenque, as at Mitla, the oldest work is the most artistic and admirable. Over this feature of the monuments, and the manifest signs of their difference in age, the attention of investigators has lingered in speculation. They find in them a significance which is stated as follows by Brasseur de Bourbourg: “Among the edifices forgotten by time in the forests of Mexico and Central America, we find architectural characteristics so different from each other, that it is as impossible to attribute them all to the same people as to believe they were all built at the same epoch.” In his view, “the substructions at Mayapan, some of those at Tulha, and a great part of those at Palenque,” are among the older remains. These are not the oldest cities whose remains are still visible, but they may have been built, in part, upon the foundations of cities much more ancient.

Copyright © D. J. McAdam· All Rights Reserved